ARTURIA MINILAB 3 - A 6-month review

I have had my Arturia Minilab 3 keyboard for about 6 months now, so I thought I'd give it a proper review. It's a nifty little gadget that has managed to wedge itself neatly into my cluttered workspace (and my heart). Was that too much? That was too much, wasn't it?

First Impressions: Design and Build Quality

At first glance, the Minilab 3 looks like it was designed by someone who’s had their share of cluttered desks. It's not any wider than my Macbook, so it fits wherever my laptop does. That was one of the bigger selling points for me. I take it with me on airplanes. The TSA will give you some puzzled looks, but I know they are just jealous. I also like the sturdiness of the design. Some of the other portable controllers I have tried feel like they might snap in half if you look at them wrong. It’s got a bit of heft, which is reassuring when you’re furiously tapping out a drum beat or tweaking a filter.

Playability

Now, let’s talk keys. The Minilab 3 has 25 of them - ranging from C to C two octaves higher. They are slim, unweighted, and velocity-sensitive...perhaps too sensitive at times. It can be difficult to play something in the middle velocities. But you know, maybe I'm just bad at playing them? The slim nature of the keys takes some getting used to if you are only used to the size of a regular piano.

Speaking of buttons, the 8 RGB backlit pads are a joy...particularly to my 2-year-old. They’re responsive and perfect for all sorts of musical shenanigans, from drum programming to sample triggering - I don't use it much, but I understand this keyboard works really well with Ableton. I'll be honest, I didn't think I would use the drum pads, but I've found a lot more use for them than I expected.

What I haven't used is the knobs and faders - of which there are 8 and 4, respectively. I may find uses for them eventually, but my goal wasn't really to use every feature of this keyboard - I just needed to replace my old full-sized midi controller with something smaller, and more affordable.

Inputs and Outputs

I will say, the USB port is nice. But, I only have two of them on my computer, so that can be a bit of a problem sometimes since I also use the Focusrite Scarlett, which is also a USB. I don't know what I'm saying here as a solution? Maybe Apple just needs more USB ports in their Macbooks.

Software Integration

It comes bundled with a bunch of softwares (including Ableton Light)...and I haven't used any of them. I was mostly interested in its compatibility with the softwares I already use in my workflow: namely Dorico and Logic. In that department it does exactly what I need it to do. I can hook up the Minilab, load in my library of choice, and off we go.

Conclusion

Overall, the Minilab 3 has proven itself to be a trusty sidekick. It has made my workstation more efficient, and I can take it on the road. It has an older brother - an 88 weighted-key version that I will definitely be on the lookout for when I am in the market for one.

The Arturia Minilab 3 has found a permanent spot on my desk and in my creative process. It’s compact, powerful, and incredibly user-friendly. Whether you’re a seasoned pro or just starting out, this little controller packs a big punch. It's not perfect, but it fits perfectly on my desk, doesn’t overwhelm my workspace, and it offers all the features I need to bring my musical ideas to life. If you’re looking for a MIDI controller that’s both versatile and space-saving, the Minilab 3 is a fantastic choice.

Four Questions for Writing Emotion in Music

Music is often emotional, and music often tells stories.

A number of years ago, I noticed that when it came to crafting emotions, and structuring my story for my music - I was usually choosing defaults.

"I'll write a happy song, and it will have 2 verses, 2 choruses, and a bridge." Nothing wrong with that. But, I hadn't intentionally decided whether or not those were the best way to express what I wanted to say.

The first thing I realized was that a good story usually has more than one emotion.

"They were happy, they stayed happy, they lived happily ever after." It's monotonously static. You need more than that for a compelling story.

So, how do we structure our stories, and convey our emotions in a musical way? Here's what I came up with: I ask myself these four questions for every song or piece I write - often before I start writing.

1) Polarity. What is the primary emotion? What is its opposite?

A lot of my music is based not just on two different emotions, but on a contrast of emotions. Emotions don't exactly have concrete opposites (like, Up and Down). Sure, maybe the opposite of Happy is Sad. But what if it is Anger? What if it is Melancholy? It all depends on the story you want to tell. Love can be the opposite of Hate, but it can also be the opposite of Indifference. Asking this question helps me understand the big picture structure of the song.

2) Gravity. Where are we being pulled? What is the force creating the pull?

You could ask this in a musical sense (as in, the leading tone is pulling us to the tonic). But you can also ask this in an emotional sense to help you figure out where your piece wants to go.

3) Journey. What is the emotional journey from start to finish?

If polarity helped me understand the structure from 30,000 feet, Journey is the specific twists and turns the piece took to get there.

There may only be two emotions in the piece - in that case, this is a roadmap of how they interact. But, often there are a lot of emotions, and only two that are primary. Then I need to ask, how do these emotions weave their way into the narrative.

4) Arrival. Where did we end up?

Some composers (and listeners), strongly prefer that the piece end in a logical and expected place. Perhaps that is the most musical choice. "And they all lived happily ever after."

But one thing I like to try is to subvert expectations - try to end the piece with the listener in wonder. Either amazement because they didn't see the ending coming, or, in reflection because I left the ending ambiguous, and it is almost up to the listener to decide how exactly it ended.

Of course, all of this speaks very little to converting emotions into music. That tends to be a highly subjective topic anyway. But, what I'll do with this information after I've done this exercise is to write down every single technique that I can come up with that will convey those emotions using the instruments I have on hand for that piece.

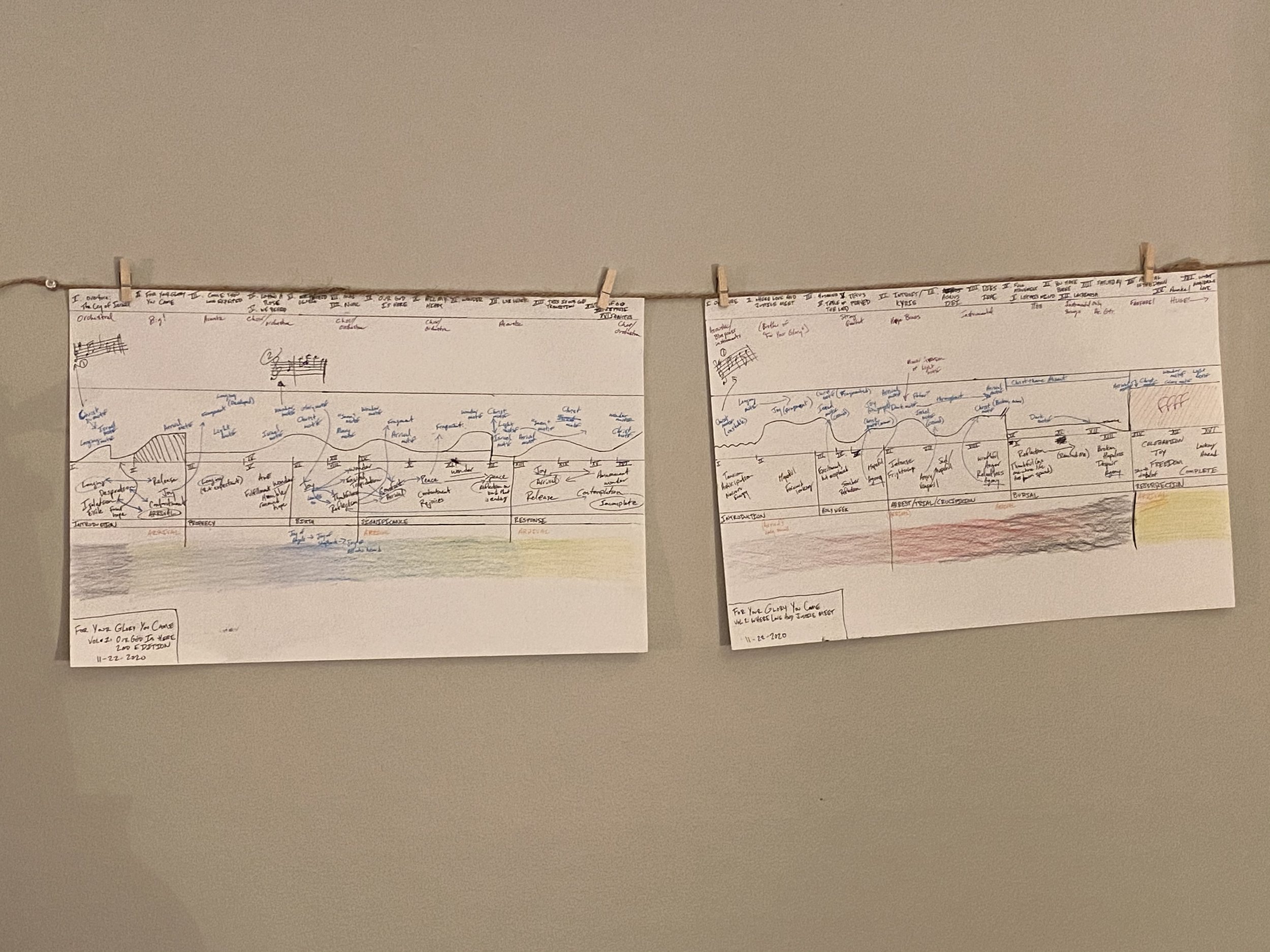

The picture I've attached is from a piece where I wanted to create uncertainty - almost like a fog or a mist; and to the right you can hear how that translated to music.

How do you create emotion in your music? Is it a process like I have just spelled out? Or does yours flow a little more fluidly? Let me know in the comments below.

And if you find this insightful, consider subscribing to my email newsletter:

If you’re looking to learn more about composition and would like to work with me, I’d love to tell you about the different options I’ve got for that. Click here to learn more!

Setting Realistic Writing Goals

To be clear:, I’m incredible at setting goals; I’m terrible at setting realistic goals. Maybe you’re there too. We get all of these amazing ideas in our heads.

I’m starting a composition #100daysofpractice or a #100daysofwriting whatever you want to call it - I’d just like to be more consistent. Well, I need a plan of some sort for where I’d like to be at the end of the 100 days (sometime in June) - and that’s where the problem lies. So, I thought “what if a student had asked me that question?” And well, we will see how it goes but here are three things I’ve come up with for setting realistic composition/songwriting goals.

Figure Out Appropriate Pacing

Take a look at your recent writing output. How much have you written over a certain period of time? You can probably expect your output won't be significantly more than that. Perhaps you finished 1 piece/song last month. You're probably not going to suddenly write 10 this month. Set a goal of finishing one piece/song, and if you get to more than that - Great!

If one of your goals is to be able to write more/write faster - then start where you are and work your way up incrementally. You can do this by setting Input Goals: "I will write 30 minutes each day." And if you want to build up incrementally: "Each week, I will add 10 more minutes to my writing time." Of course, all of that depends on your schedule and how much time you can actually devote to writing.

2. Factor in things that are writing adjacent.

I'll often work all day editing a manuscript and then feel like I didn't write at all that day. Which isn't true. These things that are associated with writing are critical parts of the writing process. These are things like Freewriting and Experimentation - where you are just playing around but not actually making progress on a project. Or maybe it's studying the work of another composer for their use of techniques. Or, practicing new techniques on your instrument - or figuring out with players what is physically possible or comfortable. Or perhaps like I mentioned, editing and revisions. All of these things are crucial, but they take time, and we need to factor in those things for setting realistic goals.

3. Set goals that are consistent with your long-term goals.

I have had periods where I wrote what I felt like I was "supposed to" write. If there's no one commissioning you to write a piece, there's no reason to spend time writing a piece you don't want to write. Make sure the things you are doing on a daily basis actually line up with your desired trajectory as a composer and songwriter. What can you write today that will serve as a stepping stone to where you want to go? Don't chase after every opportunity just because it's available. Set goals based on what is going to fulfill you artistically, and what is going to help you in the long run.

So, that's where I am today. Day 1 of 100. I'll be documenting this journey so make sure to follow along from now until June, and we will see where I end up.

Anyone Can Write Music

Writing music is a craft. It's not a rare gift only given to a select few. And because it's a craft - all musicians can and should write music. And today I’ve got an exercise for you to help you get started.

Writing Music is like Writing Language

Let's think about language for a second. That's what I'm using right now to communicate with you. I could have chosen to communicate with you through a series of colored dots - but that wouldn't have been as effective.

In order to communicate with language, you need to be familiar with that language. I can put together sentences of words and you understand them because I know a lot of words and their meanings, I know sentence structure, and I know what it is that I want to communicate. I'm not inventing any new words to communicate this with you - but I am writing. Well, speaking in this case - but I did write it down in the script before I started speaking. Well, and actually before I wrote this script I spoke these thoughts into my voice memo app. And before that, I actually wrote these... [It cuts off, I start the camera over] You get the point - these are thoughts that I am communicating, and I am capable of that because I have learned English. And these particular thoughts do not require me to revolutionize linguistics.

In the same way, all musicians have within them the ability to communicate through writing music - because they know music.

Composition is Just Expression

Just because you have it inside you, that's not to say you'll immediately be good at it. That seems logical enough. My daughter when she was learning to talk would put together sentences like "me want doing swing", but she kept practicing and now she knows that "I would like to swing" better communicates what she wants.

All composition is just a musical expression. And you "getting better" at composition is you getting better at communicating that expression. And like with everything else in life, that happens through practice.

There's never been more resources

And you'll need to practice quite a bit. But it's worth it. And you might say "I have no desire to compose for a career." But I think literally every single musician can and should regularly express themselves by writing their own music. I write a lot of English all the time despite not being a career Novelist. My goal in writing in English isn't to have my books read by the whole world. I wrote a text message a few minutes ago, and it doesn't mean that I have intentions of become Geoffrey Chaucer.

You've got a lot of resources to help you - more than there have ever been. Countless videos and courses on the internet that you can learn to write music. I had none of that 20 years ago when I was learning to compose.

Not only that. But there are so many resources for you to experiment and learn on your own. With DAWs and Instruments and what not. Spitfire Audio has a free version of their BBC orchestra library that gives you access to practice with a full orchestra. It's Crazy.

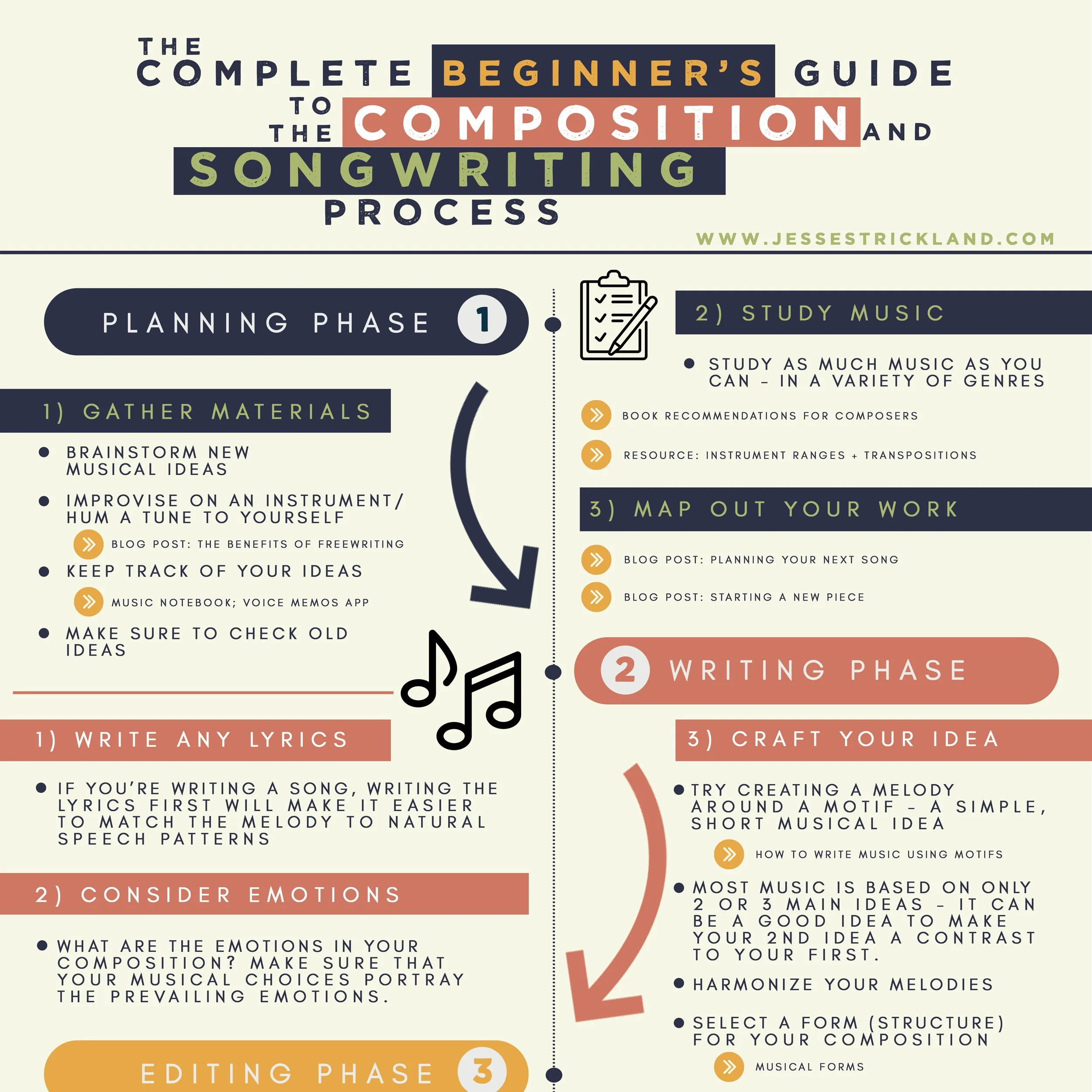

I've got a free resource for you today. I've heard from a number of my composition students that keeping track of the whole process of writing a piece is often overwhelming. So, I've got this interactive PDF that outlines the composition process step-by-step. It's got links to 16 additional resources that I think you'll find useful.

A Writing Exercise

If you're still thinking "well, that makes sense - but I already know that I can't write music," I want you to try this exercise. It's going to feel awkward. Fight against that feeling. Composition is messy. And here’s the thing. Our goal today isn’t to write a whole song, or a whole piece. The goal is to just write something. Here’s what I want you to do:

Step 1. Take out your phone, and find your voice memo app.

Step 2. Hum something to yourself. Anything. Long or short, doesn't matter. Don't worry about whether or not it is good. Don't overthink it. Just hum something.

Step 3. Do it again. You might as well leave that voice memo going - you never know what's going to happen. Try to get up to five.

Step 4. Listen back to your voice memo. Let's go ahead and quickly come to terms with the fact that it isn't a Radio quality recording and move past that.

Step 5. What do you feel like each snippet is expressing? Happiness? Confusion? Hunger? If composition is expression, what do the melodies you've come up with express?

Step 6. Identify some fragments that you really like. You're looking specifically for something you could build off of. Again, don't be too critical. You're looking for something that you like, not something you think is good. Or, even what you think other people might think is good. Your identification of things you like is a proof of concept that you can write music.

Step 7. Repeat this entire process quite a lot. Hum to yourself all the time. Eventually, humming a melody will be much easier. You'll end up liking more of what you came up with. And you'll better be able to say what your melodies are expressing.

I'd love to hear from you: do you compose music? If so what kind of music do you write? How did you get into writing music? And if you don't write music - do you want to? What obstacles do you see that keep you from it?

Planning Out Your Next Song

[Note: This is post #2 in a five part series on the composition process. If you have not read the introduction post, you can do so here. If you would like a free PDF of the material we’re covering, you can get your copy here.]

Now that we have an overview of the process, let’s zoom in and take a look at each of the phases - starting with the Planning Phase. Planning is a crucial part of the composition process, and it can set you up to have a much smoother writing experience. Maybe planning is something you do every time, or it may not be something you’ve ever thought about. I’ve got four steps, and they should help you stay organized in the writing process.

The Importance of Planning

First things first, let's talk about why planning is so important. By taking the time to plan your composition, you can:

Create a roadmap for your music

Stay organized and focused throughout the writing process

Create a cohesive and intentional piece of music

Avoid writer's block and other creative roadblocks

Improve your productivity and efficiency

Avoid creating problematic music, that you might have to go back and fix all of those mistakes later.

Without a plan, it's easy to get lost in the creative process and lose sight of your goals. I sometimes get caught up in just writing, and almost inevitably I end up having to go back and come up with a plan so the piece isn’t a complete mess.

Other times, you might hit a wall and have no clue where to go with the piece next. But, with a plan, you can always go back and check the map. Having that plan will usually improve your efficiency in writing the piece.

Collect Musical Materials

Before you start planning your piece, collect musical materials that will serve as the building blocks for your composition. Maybe you’ve had an idea in your notebook, and now you’re getting around to writing it. Maybe you’ve got sketches all over the place (on napkins and whatnot) and they need to be consolidated. By collecting these musical materials, you'll have a pool of resources to draw from when you start planning your piece.

I used to try starting from absolute zero with a plan, and then I realized that was a terrible idea - at least for me. It’s definitely better to have some materials that you can use to create a plan with.

If it’s a song with lyrics, I will at least have some of those lyrics on hand for this planning phase. You don’t have to have all of the lyrics completed, just enough for you to know the central ideas of the song.

Purpose of the Piece

What kind of music are you creating, and what's the goal of the piece? Is it a pop song that you want to pitch to a record label, or a cinematic score that you want to use in a film? Defining the purpose of your piece can help you stay focused and ensure that your composition aligns with your goals. Of course, not all music has to have some greater “purpose”, it can just be music. Also, if you’re writing for a performer or ensemble, they might have some purpose for the piece (like an anniversary, or the dedication of a new auditorium…something like that)

You might also consider what sort of meaning the piece has. Is it a love song? Is it a piece about the grandeur of nature? Is it a piece that represents some scientific or mathematical principal? Again, music doesn’t have to have a “meaning”, but if it does, the planning phase is a good place to figure that out.

Scope/Instrumentation

Next up, it's time to consider the scope and instrumentation of your composition. What instruments do you want to use, and how will they work together to create a cohesive sound? How long will the piece be? Is it multi-movement? Is it a single song, or an idea for a full album?

Sometimes this is really easy. You’ve been asked to write for a particular ensemble, and that ensemble has given you some parameters. Like this piece I wrote for a percussion ensemble. It was for 4 performers, and I was told to keep it under 15 minutes long. Furthermore, because of the nature of this ensemble, I was asked to only use metallic percussion instruments. So, those decisions were made for me; which means in the planning phase, I wasn’t deciding which instruments to use, so much as how I would use them.

Other things to consider here (and it’s okay if you don’t know them just yet): What key will you be in, and what tempo will you set? Consider the genre and style of music you're working with, as well as the emotional journey you want to take your listeners on.

Emotional Journey

Speaking of emotional journeys, it's important to think about the emotional arc of your composition. What kind of mood or atmosphere do you want to create, and how will you achieve that through your musical elements? Consider how the melody, harmony, and rhythm can work together to evoke different emotions and feelings in your listeners. You might even want to create a musical map that outlines the emotional journey of your piece, from the opening notes to the final resolution.

Timeline on an 11x17 paper

I like to start all of my pieces with a timeline, that I put on a single 11x17 sheet of paper. You basically start on the left with the beginning of the work with the end of the piece on the right. I like to start by marking time (in minutes and seconds). Then I’ll place the materials that I know I have where I want them (major themes, melodies, etc). You can also mark down emotion words, and colors, and energy levels - all the stuff you just figured out in that emotional journey section.

The Resources I Use

So what do I like to have on hand to plan a piece of music? Honestly, all you really need is a piece of paper and a pen to do what I have suggested above. But. Here are some items that I have found very handy in this process.

1) Like I just mentioned, I like to work on 11x17” pieces of paper. It just gives me more room for ideas. 8x11” is totally fine too, if that’s what you’ve got on hand.

2) This is my sheet music book of choice. It’s got 18 staves, so it’s great for working with a lot of instruments at once. If you want something more notebook sized, this is a good choice.

3) This is a pen that has 5-points so you can draw a music staff on a blank paper. Very handy.

4) I like to have a ruler on hand for marking straight lines and edges.

5) You might also find it helpful to have an instrument nearby - but honestly, I like to do this stage of the process without an instrument so that I focus on the planning, and not on the writing.

Final Thoughts

Planning is an essential part of the music composition process. By taking the time to collect musical materials, define the purpose of your piece, consider the scope and instrumentation, and create an emotional journey, you can create a cohesive and intentional piece of music that aligns with your creative goals. Plus, by creating a timeline to guide your composition process, you can stay organized and productive from start to finish.

But. Here’s the other extreme - that I’m also guilty of: you can spend so much time planning the piece that you never actually get around to writing it. At a certain point, you’ve got a good enough plan, and you’ve just got to start writing. The piece will become something you never intended - but that’s okay, you’ve also got to be willing to listen to what the piece wants and where it wants to go…but that’s a completely different blog post.

So - if you’ve never done it before - the next time you sit down to write a new piece of music, take the time to plan it out. It may seem like an extra step, but in the long run, I have found that it will save you time, energy, and headaches.

Next time, we will talk about the actual writing phase of the composition process. I hope you’ll join me. Make sure you’ve got your copy of the Beginner’s Guide to the Composition + Songwriting Process.

further reading

Introduction to the Composition + Songwriting Process

Why have a Process?

There are a lot of steps and a lot of moving parts when writing a song, or a piece of music. This is why it's really easy to get stuck and frustrated, or even to abandon a project entirely.

It's much easier to accomplish anything if you've got a plan. And for years in my own writing journey, I would constantly get stuck. Whenever I would begin a new piece, things would start off great, until I hit some sort of a wall, and it was like trying to reinvent the wheel every single project. So, I finally had to sit down and write out my personal process for writing a piece of music. Anything that I did that made writing a piece easier, or anything that if I didn't do - I'd have to come back later and do it anyway. Take all of that and put it in a nice linear format, and you've got yourself a bit of an algorithm for writing music.

Of course, it doesn't quite work that nicely. Composition is a messy art. It's not linear, and that's exactly why you need a map. Something you can go back to when you end up lost off the beaten path and unsure which way to go now.

Each and every composer needs their own personal process - we each have a different brain. Our field is an art. This is not a McDonald's, where the goal is to put out an identical product each and every time. We each have our own voice, and our own personality, and our own workflow which produces the results that we want.

However, I think there are four phases to the composition process, regardless of the composer; regardless of the style of music, or era of history.

This is the start of a Five Part series, taking an in-depth look at the composition process. Today, I'll just give an overview of the four phases, and then the next four posts will look at each of them in more detail.

What makes it a composition?

Let's start by defining a composition. There are many ways to write music, and a composition is a specific type of written music. All of the types of written music are valid and good, I'm not trying to elevate one over another, I'm just trying to focus all of us on the same idea. Disclaimer: These are the definitions I'm giving for the sake of this series, other musicians might have varying definitions.

1. A Composition is Original

A composition is a work of music that is new and original to the composer who wrote it. This distinguishes a composition from an arrangement, or a cover. With arrangements and covers, (generally) another composer wrote the source material, and you are just putting your own spin on it. This takes a great deal of skill and consideration, but it's not what I'm talking about in this series. Maybe we'll do a different series on how to do a cover.

So, a composition then, is a work that all of the material is original to the composer (or composers, in the case of a co-write). That's important for our purposes because it gives a composition its own specific process.

2. A Composition is different from an Improvisation

The fact that a composition is planned separates it from an improvisation. You'll often find musicians who have a propensity towards one or the other. I am on the composition side. I have very little ability to improvise. I find that it is very similar to those who can stand up and give a rousing speech of the top of their heads, versus those who do much better to sit down and carefully craft a novel. It's often two separate skill sets.

There's also no editing an improvisation - you know, by definition. Once you've played your saxophone solo, it's over - there's no redo. Of course, once you get into the recording studio with jazz musicians, the line between composition and improvisation starts to blur.

But here we are talking about a planned, crafted, and edited work of music - known as a composition.

One other note: Some might make a distinction between a composer and a songwriter - but I do both and they both have the exact same process for me. So, these four phases apply to both songs and instrumental compositions.

A Free PDF

For this series, I've made an infographic PDF of the entire composition + songwriting process that we're talking about - and it's free when you sign up for my email list. It's also an interactive PDF, so it has links to 16 additional composition resources. You can get your free copy of it here, and follow along as we go the next four posts.

The Four Phases

So what are these four phases? You can break the composition process into the Planning Phase, the Writing Phase, the Editing Phase, and the Transferral Phase.

Planning Phase

Like I mentioned earlier, a composition is planned. Even if you start with a template (say "Verse, Chorus, Verse, Chorus, Bridge, Chorus"), that's still a plan. You're deciding a number of things about the piece before you actually get into the writing of it:

- What's it going to be about?

- What instruments are involved?

- What compositional techniques are you going to use?

- How long will it be?

- What emotions do you want to portray?

And maybe you don't know the answer to some of these things to begin with, but I have found deciding on some of these things before I start writing makes the process go a lot smoother.

The planning phase can look vastly different depending on the style of music. If you're writing film or video game music, the planning phase is very different than a piece that is not written for picture.

Writing Phase

Once you've got a pretty good plan, it's time to start writing. I have found this to be the least linear phase out of the four. I often like to think of the steps in this phase as a checklist rather than a progression. I'll work on a lyric here, a melody there, go back and work on that lyric, then oh, I just had an idea for the B section. It's a rather messy endeavor. This particular section is the place where I get lost most often - but that's why I developed a process. I can always go back and look at the process, and I can also go back and look at the plan I made during the planning phase.

The goal with this phase is to end up with a first draft. I tend to not try to do any fixing during this stage - just get it all out of my head as quickly and as orderly as possible.

Editing Phase

Three main things happen for me in this phase.

1. A music edit. I go back and listen to see what isn't working. A horn part that is not playable. A section where the pacing is too slow. A lyric that's clunky and a little cheesy. A transition that was too abrupt. Those sorts of things

2. Go look for feedback. Composition can be a lonely sport. You've been in your own head the whole time, it's time to bring some other brain into the process.

3. A Notation edit. Unlike the music edit, I'm just looking for things that are out of place in the score this pass. That dynamic marking is in the wrong spot, these two staves are too close to each other. Are my page margins wide enough? Super tedious stuff. Also, something that you may not need to worry about if your goal is to recording.

Transferral Phase

This one might need a different name, but it's the best single word I could find to describe this part of the process.

So we have our final composition - there are typically one of two goals:

1) Record it for audiences to listen to

2) Write it down to hand to players who will perform it for an audience to listen to

Obviously, this particular phase might depend on which style of music you're writing for - as more classical music tends to be the second option, and more popular music tends to be more of the first option.

Of course, there's always that third option where you're going to both write it down, and record it.

The point in all three of these options is that you are taking this idea that was in your head, and you are turning into something that can be understood by another human.

The Series continues...

So, that's a quick overview of the composition process.

Stay tuned for the next four posts where we will look into each of the four phases in detail. Starting with Planning Your Composition.

In the meantime, make sure to get your copy of the Beginner's Guide to the Composition Process.

How To Start (Over)

I’m trying to start writing music again - after about 6 months off.

I didn’t mean for it to happen…but sometimes life happens. And I think we have to be okay with that.

It’s an interesting to be working through. It’s not like I’m doing something I don’t like, or even learning something new.

This is a journal entry, of sorts, into my journey of starting over. I’ve got three thoughts that I hope will help you if you are in the same place.

1. Start Small

If you’ve been on an extended hiatus from composing, you might want to just try jumping back into your old routine. Let me tell you from my recent experience - it doesn’t work. It’s like I was a marathon runner and then I did nothing but sit on the couch and eat potato chips for five years…and my first day back I tried to run 20 miles…at my old pace.

Taking a break is fine, a slow start after a break is fine.

So, I’ve been trying to write for 5 minutes a day. Only 5 minutes. Whatever I get done in that time is what I get done. I’m going to stay at 5 minutes until I feel like I can write longer.

As you can imagine, not much can get done in 5 minutes. And that’s okay. But, it didn’t take many days until I had forgotten about time and I was going for 10 - 15 minutes.

So - give yourself the grace to start small.

2. Establish a Writing Routine

Once you’ve gotten back in the habit of showing up every day and writing - establish a writing routine.

Now. A quick caution here. If you had a writing routine before your hiatus, it might not work this time around. Your life situation may have changed, the amount of time you can devote may be smaller. And also, this is just the second step after ‘write for 5 minutes.’ So, establish a writing routine that will facilitate your composing where you are right now.

Establish when and where you will write. How long are these sessions? What do you want to accomplish? Remember to be realistic. Your answer here shouldn’t be: “three hours, and I’m going to write a 30 minute concerto today.” But maybe like, “a 30 minute session where I’ll write the A theme for a solo piano piece”

3. Find a Community

Composition can be a lonely sport. You just sit at your desk, just you and your thoughts. It can be very isolating. You also might have the pervasive thoughts:

“I’m the only one going through this.”

“Maybe I just don’t have it anymore”

“Everything I write is garbage”

I promise, there are other composers are feeling this. (I’d also like to say parenthetically, your identity as a composer isn’t based on productivity) A really good strategy for combatting this is to find a community of musicians and composers who are trying to learn and get better together.

That’s what I’m seeking to create with my new YouTube channel. You can check out more about that here.

There are also a good number of online communities that you could plug into. The /r/composer subreddit is a pretty good one - you can ask all of your questions, ask for feedback on your work, and see that there are others who are in your boat with you.

So, if you’re trying to start over, don’t get discouraged. Try these three things. And remember, it takes time.

Remember why you fell in love with composition in the first place. And just write.

Which Notation Software Should I Use?

For any composer/arranger/songwriter who uses staff notation for either writing or performing, you'll more than likely need a notation software. Maybe you want to write it out by hand, but I don't recommend it. It will obvious look much cleaner, and more professional to have your music engraved by a notation software.

How do you know which one to use? Pretty much all of them claim to be the best software on the market. With a multitude of notation software options available today, each boasting its own set of features and quirks, it's natural to feel a little overwhelmed when trying to pick the best one for your needs. Today I'll attempt to guide you through the labyrinth of musical notation software.

Most of the notation software options available have both a free and a pro version - obviously with the free version having less capabilities than its premium counterpart. Which one you need will be dependent on which capabilities you need your notation software to have. Also note that many of these software have some sort of Education Discount.

Noteflight

Noteflight Basic

This is an online software that I would recommend if you have been given a composition assignment in a class and need a free notation software. Very user friendly even for beginners, and it has plenty of features, but you are limited to 10 scores in the free version. So, if you only need it for somewhere between 1 and 10 projects - you're gold.

Noteflight Premium

But, I'm going to bet in the process of creating your first 10 scores, you get really hooked on this whole music writing thing, and you'll want to make more. You can upgrade to Noteflight Premium for either a monthly or a yearly subscription. Premium is where Noteflight really shines. You'll have access to all of the notation input features, but also access to over 80,000 digital scores that are in the Hal Leonard collection. While I think this is a good choice for all composers - it's probably the best choice for those who are looking to do mostly arrangements because of the access to the Hal Leonard catalog. Noteflight also has a great collaboration feature, making it a good choice for ensembles.

Not only that but you've got access to the ArrangeMe platform - Hal Leonard's platform for selling arrangements. If you work with arrangements, you know how difficult it is to jump through all of those legal hoops. Here, most of that is taken care of for you.

Conclusion: Best Choice for Arrangers, A Cappella Ensembles, and Educational Use

Dorico

Dorico SE

This is Dorico's free version. You are not limited by printing or number of scores, but you are pretty limited in terms of the customization (which in my opinion, is what makes Dorico stand out). Many of the options are fixed for you, and you are limited to 8 instruments on any given project.

Dorico Pro

A friend of mine in grad school was a beta tester for Dorico and he introduced me to it, and I was instantly hooked. I originally switched to Dorico because of its capabilities with microtonal accidentals. It has the ability to do most anything you can imagine for staff notation. In my opinion, this software is the most intuitive and user friendly. The amount of customization that you can do with Dorico is almost inexhaustible. I recommend this for higher education and professional composers who specifically need advanced features from their notation software (ie, microtonality, etc). This software is a one time payment (until you want to upgrade). This is my every day notation software, and my performers have always been thrilled with the clarity of the final scores.

Dorico also has a great capability for scoring to picture. So, if you are a film or TV composer (or, are pursuing that path) this might be the software you need. I personally don't do any scoring for picture, so I can't fully speak to its full potential there.

Dorico is from the same developers as Cubase, which makes them rather compatible, if you have Cubase as your recording software.

Conclusion: Best Choice for professional composers, film and tv composers

Sibelius

I don't really have anything good to say about Sibelius. In all of my experience with the software, it's glitchy, it constantly crashes, it's not terribly intuitive, and it hasn't really improved with new software updates. It's also got a pretty high price tag. Anyone who has ever used Sibelius probably has trauma related to a “Sibelius has unexpected stopped working” error.

That being said, it's been around for quite some time and at one point was likely the most popular. I know there are a lot of professional composers who still have Sibelius as their primary software. So, this is just my experience with Sibelius - your results may vary.

One other thing: it is from the same developers as ProTools - so the two are fully integrated. So, if you use that as your recording software, you might give this a try.

Conclusion: Choose something else

Finale

This was my first notation software. I found a free version of it way back in like 2005 or something. I used it for over a decade until I switched to Dorico. It's fairly easy to use, but it has a moderate learning curve. I wrote my first major work using Finale, and it was fine. Their website make it sound like it's a way better software than it is.

For years, Finale and Sibelius were like your only two choices - so a lot of professional composers are still Finale users. It has all of the features you're probably going to need.

My biggest complaint with Finale is 1) sometimes you can make a small change and it will completely destroy all of your formatting (like Microsoft Word does sometimes), and 2) it doesn't always make the best decisions when it comes to notation layout. I have spent hours fixing mistakes that Finale made when I input something. You've really got to know your notation standards to know what is correct.

It is much cheaper than Dorico and Sibelius, and it has a good educational price point. So, if you end up learning Finale because it's what is in your school's computer lab, you might just end up sticking with Finale.

Conclusion: If your choice is Sibelius or Finale, choose Finale.

MuseScore

According to its website, it's the most popular notation software - perhaps because it is the only one on this list that is entirely free. All of the capabilities of MuseScore come without cost, it's a free download, and a great software. For the price, the playback instruments in its latest version are incredible (just go look some up on YouTube). This is a great no-risk software for new composers who are trying everything out. If you decide composition isn't for you, you haven't lost anything. But, even if you keep going, MuseScore probably has most everything you'll need. However, I have found for me personally, I don't like the user interface as much (even though it has GREATLY improved from its previous versions)

It's also Open Source, so it's always improving, and you don't have to wait years for a software update. It is very easy to share your music, and have your music found by others.

Conclusion: Best Choice for brand new composers, hobbyist composers

Final Thoughts

To wrap all of this up - you can honestly use any of these softwares successfully.

Consider these factors:

- Price you're willing to invest

- Specific capabilities you need

- The user interface that you find the easiest/most natural

- Sharing functionality that suits you

Perhaps you'll even have to weigh which of these factors are most important (give up some functionality for a lower price, etc.). It's likely that all of these have a free trial, so I do recommend trying each of them out and seeing which one you like the most. At the end of the day, the best software is one that is capable of getting your musical vision in writing in a way that the performers will best understand, and won't cost you your sanity in the process.

One last question: Do I actually need a notation software?

For any composer/arranger/songwriter who uses staff notation for either writing or performing: Yes, you'll more than likely need a notation software. However, not every musician uses staff notation. Maybe chord charts or lead sheets is more common in your genre. Don't feel like you have to use staff notation to be a musician. In that case, you probably don't need a notation software - you might be better served by a recording software.

Top 10 Book Recommendations for Composers

One frequent question I get from younger composers is "what books should I read to study composition?" So, I've got my top 10 books that have been foundational for me in my career (both as I was getting started, and even still today).

1. Fundamentals of Composition (Arnold Schoenberg)

2. Theory of Harmony (Schoenberg)

If you know anything about Arnold Schoenberg's music, it might seem odd that I have these books on my list. But, they are simply wonderful books for new composers. He breaks everything down in a very accessible way. No book has impacted how I think about composition more than the "Fundamentals of Composition."

This is the gold standard when it comes to music notation. I cannot recommend this one enough.

As a composer who works with classical ensembles and is also self-published, this book is one of the two books that literally lives on my writing desk. After I was rather embarrassed at a rehearsal where my score and parts were (to be honest) rather unprofessional, I had a professor recommend this book to me. I studied it furiously, and it has made all the difference in my score presentations. If you use staff notation which will be read by performers, this book is pretty much mandatory.

4. Study of Orchestration (Samuel Adler)

The other book that lives on my desk. It was first published in 1982, so some orchestration ideas might not seem as relevant today. But it is comprehensive. It works its way through every family of instruments giving you just about everything you could need to know for writing for that instrument. Note: it is definitely more geared towards writing for those instruments in an orchestral context.

All that being said, I reference this book almost daily. Even if you are a complete beginner to orchestration - this book will be a great guide for you.

5. New Musical Resources (Henry Cowell)

First published in 1930, this book was rather groundbreaking at the time. It explores innovative concepts in both composition and music theory. For the time, many of the approaches to rhythm, harmony, and timbre would have been considered unconventional (like tone clusters, rhythm scales, negative harmony, etc) It really showed the potential of non-traditional instruments and techniques - particularly extended techniques.

While these techniques may seem common now, what I really like about this one it how it encourages composers to break free from conventional musical practices and explore new creative possibilities.

6. 20th Century Harmony (Vincent Persichetti)

The techniques of the 20th century in Western music were quite the departure from traditional techniques. This book gives a great overview of the music theory of the early 20th century. It was published in 1961, so it only covers the music of the first half of the century - namely Schoenberg, Webern, and Berg.

20th Century techniques can be rather confusing to beginners, but this book does a great job of explaining complex topics. Being that the early 20th century laid the foundation for what is currently happening in classical music - this book is highly recommended.

7. Study of Counterpoint and Fugue (Joseph Fux)

An absolute all time classic. If you've ever taken a music theory course and wondered where all of those rules came from - it's probably this book. This is a pedagogical book - meaning it was written for students - and it serves its purpose well. You just need to remember its purpose when reading it. The training in counterpoint that it will give you is a great foundation, and it will give you valuable skills as a composer, even if you don't follow exactly what it says (because if you do, you'll end up sounding like Bach but worse.)

In classical composition training, composers were taught orchestration, and counterpoint; and this book is a great place to go if you want to learn counterpoint.

8. Music of the Lord of the Rings (Doug Adams)

This is my personal favorite of the bunch. Unlike all of the other books, this one is simply an analysis of the soundtrack of the Lord of the Rings trilogy. Apparently, they knew they were on to something good, because during the production process, Doug Adams followed composer Howard Shore around, taking detailed notes about absolutely every single facet of the film's score. The result was nothing short of what I'm sure will prove to be one of the best composition books of the 21st century.

In my estimation, the Lord of the Rings music is by far and away the best film score of all times. So, if you are looking to go into film scoring - you need this book. Study every page of it. But, also if you're a Tolkien nerd - you need this book.

9. Techniques of the Contemporary Composers (David Cope)

This was the first ever composition text I read. I just happened upon it in a public library. At the time, I hadn't received any composition training - I was just eager to learn. So, I read it. And though I didn't fully understand all of it at the time, I was hooked.

"Modern" always lends itself to irony, as this book was published in 1984...and is no longer modern. But it does pick up where the Persichetti book left off, and covers the major composition trends of the later 20th century, namely Minimalism, Aleatoric and chance music, electronic instruments, and microtonality.

10. Choral Arranging (Hawley Ades)

As a primarily choral composer, I have spent a lot of time with this book over the years. I have found that on the whole, many composer who are not choir members themselves are greatly under-educated about writing for choir. And as a choir member, I can tell you it's usually very obvious from their writing when a composer has not sung in a choir themselves.

So, I highly recommend this book if you are a composer who is looking to write for choir in any capacity. It walks you through proper voice leading and voicing, text setting and clarity, even the ranges and registers. Do all of your singers a favor and memorize this book.

Further Reading

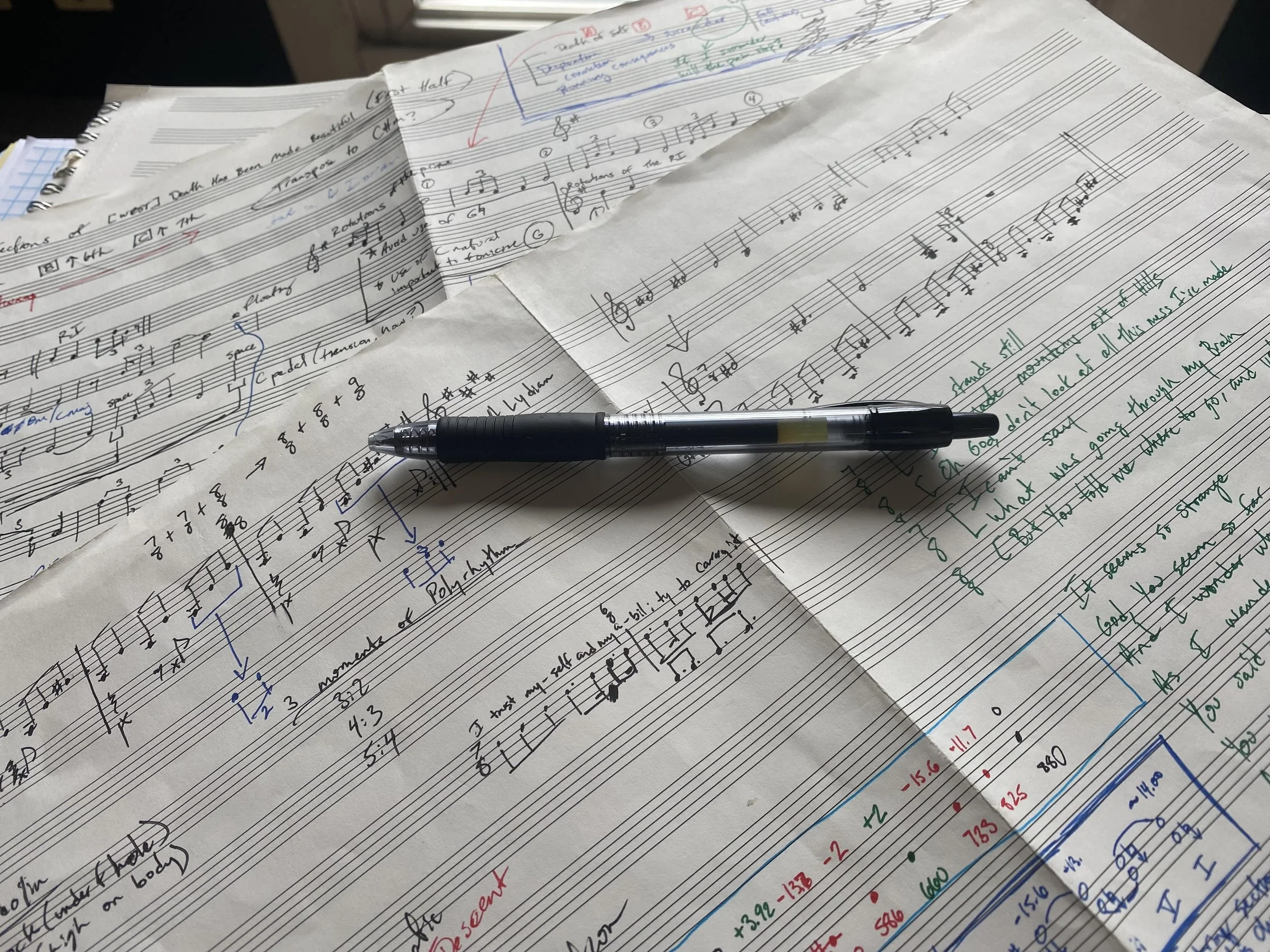

Embracing Chaos in the Writing Process

The composition process is not a straightforward process. It's quite messy.

But we often want it to be streamlined and efficient. "If I just do x, y, and z; I'll have a piece of music." It's even more frustrating when we look at other composers, and it seems effortless for them. You hear stories of songwriters that wrote a song in 15 minutes, while you're sitting there dealing with writer's block, and you think there is a problem with you:

"Maybe if I was just a better composer, I wouldn't be struggling with this"

The problem is not your skill level, but your expectations. The chaos in the composition process isn't a flaw, but a feature. The goal isn't to get rid of the mess, but to use that mess to our advantage. After all, you can't make an omelette without breaking a few eggs, right?

Here are three ways that we can embrace the chaos in the composition process.

1. Write What You Know First

Notation Softwares, by their nature, force you into linear writing starting at measure 1.

Recording softwares do as well. When you open up a new project, there is a clear expectation that you are working from left to right, and you need to know what you're doing every single measure.

But that's not always what you know. You may only have a lyric fragment or a motif, and you don't know exactly when you're going to use it. Don't give into the temptation to start at measure 1. Write what you know first, and then work your way out from there.

That's one of the reasons I like working on paper - I can work more freely in space. I will either work on large orchestra paper where I can spread out my thoughts, or in a little moleskine notebook that I can carry on the go with me. Both of these options allow me to sketch out ideas without needing to polish them. And they are both helpful when it comes to [starting a new piece].

2. Get To The Double Bar

Speaking of polishing an idea: Don't worry about perfecting any one section - get to the double bar. What do I mean? As quickly as possible, sketch out the entire piece (without having every single answer to every question). Think of this as scaffolding which is set up so that real construction can occur.

Before you start this, it can be nice to have a plan. A rough outline of the structure of the work. I will usually do a timeline before moving on to the short score (where I sketch it out from end to end). Note, with this sketch, I will still work outwards from what I know, filling in the gaps as I figure them out. Still don't feel the pressure to work from left to right.

Don't disrupt the flow of getting your ideas out of your head by tweaking minute details. It's difficult to just let this happen: "what if that idea doesn't make sense? what will the cellos play in that section? How is the voicing of this chord?"

All of this can feel very chaotic - almost like you have no control anymore. But it's a good thing - you are making progress, even if you've made a mess.

3. Let the Piece Tell You Where It Wants to Go

Which brings us to the 3 way to embrace chaos: let the piece tell you where it wants to go.

Your original idea might not be the best for the piece. You've got to be willing to toss out the playbook if the piece tells you it wants to go somewhere else.

There's a saying in writing that you need to be willing to cut your best ideas if it isn't what is best for the project. Even if it's the idea you thought this entire work would be based on.

I once wrote a piece and I wanted this big climax, followed by this one particular chord progression that would be a very soft pianissimo - it's the first idea I had for the piece, and I thought I was working everything else up to this one moment. But, when I actually finished the work and listened to it - I knew immediately, it didn't work. It was really difficult to cut it from the final score - but it was best for the piece.

Often, one of the reasons that the writing process feels chaotic is because we are demanding order where there is none.

further reading

Scaling the Wall: A Composer's Guide to Overcoming Writer's Block

Check out my new eBook!

Even though there’s probably not any hard research on it, I feel pretty confident stating that exactly 100% of composer’s throughout the course of history have experienced Writer’s Block. Put it right there on the list of inevitables with death and taxes.

I know this is a topic on a lot of composer’s minds. Almost every single masterclass or lecture I’ve given to a group of composers, one of the questions at the end is always about dealing with writer’s block. It’s perhaps the question I get asked most often.

I have certainly dealt with it more times than I would like - I feel like my ADHD might impact the frequency. And somehow, each and every time it feels like reinventing the wheel to get out of it. So, for the last few years, I’ve been meticulously documenting exactly what has happened when I fell into writer’s block, what I did to get out of it, and what I did to maintain creativity.

And today, I’m excited to announce that I have compiled all of those strategies into a step-by-step guide, and I’ve put that guide into an eBook for all composer’s to use the next time they inevitably fall into writer’s block.

We’ll look at 1) how to get out of writer’s block, 2) the importance of mental health and creating a healthy relationship with your work, and 3) strategies for maintaining creativity.

All of the things in this eBook are strategies that I personally use in my daily life as a composer, and I think you will find this guide immensely helpful.

So if you are stuck in the pit of writer’s block, desperately looking for a ladder to scale the wall, check out this guide.

Making Rejection Your Ally

For musician of any sort, rejection is a common occurrence…and I’ll be honest, that sucks. Whether it's a rejection letter from a publisher or record label, a negative review from a critic, or not getting the gig you wanted, rejection can be a tough pill to swallow. But rejection doesn't have to be 100% bad. In fact, if you approach it with the right mindset, rejection can be a powerful ally to help you grow as a musician. So, today I want to give some tips I’ve learned on how to deal with rejection and use it to your advantage.

1. Don’t take it personally

First off, remember that it's not personal. I know that’s easier said than done. When you're rejected, it doesn't mean that you're a bad musician or that your music isn't good enough. It simply means that the person or organization that rejected you didn't see a fit for you at this particular time. I understand that doesn’t make it any easier. But. Remember that the music industry is subjective, and what one person likes, another person may not. So don't take rejection as a reflection of your talent or worth as a musician.

This is a rather difficult thing to do. What is more vulnerable than putting your art out into the world? More often than not, It’s not just something you made, but rather it’s a piece of you.

Let’s look at some of the more frequent causes of rejection:

Composition Competitions

Wow, do I have a lot of thoughts on composition competitions. Most of them are not relevant to this discussion so I’ll try to sort through what is pertinent. Each organization who puts together a competition like this probably has a particular sound in mind for the piece they’d like. If not, then you’re looking at dealing with the particular preference of the judges. Neither of these are a reflection on you as a composer.

I love watching cooking competitions. During the judging you’ll hear discrepancies like one judge saying “my meat is overcooked” or “it’s got too much salt for my liking”, and then the next judge will completely disagree with them and say that the dish was executed perfectly. In those moments, it’s hard not to think about composition competitions and the judging that goes on behind the scenes that the composers don’t know about. I have no idea what those judges are looking for - music is a subjective art, not an objective sport. Maybe that judge just wanted a little more chromaticism, a little less polyphony, or any number of other things.

Many of these competitions even require you to take your name off before you submit, so it’s really not personal in those cases. It still feels that way sometimes.

Labels and Publishers

I feel like it’s probably difficult to overstate how many submissions labels and publishers get from musicians on a daily basis.

I once sent in a choir piece to a music publisher that I was rather proud of. The choir who commissioned it had done a spectacular job with the premiere. I was encouraged by the director of that choir to send it to a particular publisher that they had a connection to. After months of waiting, I finally got a response: “This is a beautiful piece! I love it! Unfortunately, we are going to have to pass because we don’t think it will sell all that well.”

Sometimes it’s very obvious that you aren’t the correct fit with a label or a publisher. I’m probably not getting too many record deals by sending my demo off to a heavy metal label - and that doesn’t cause me any pain. It’s when it seems like you would be a good fit, and the executives disagree that this gets hard.

University Music Programs

I’m not even going to pretend that I have even a 1% understanding of the university admissions process. But it’s definitely a common source of rejection among musicians.

Concluding this section: Some composers specifically try to get rejected a certain number of times per year. This does a few things: 1) it’s proof you’re putting yourself out there, 2) gives you a better chance of being accepted for something, and 3) firmly accepts rejection as an unavoidable reality, and in so doing that takes away some of its sting.

2. Look for constructive criticism

Okay, it’s one thing to not take it personally, and just shrug it off, but how can we use that rejection to move forward? One of the worst parts of most rejections letters is that there is absolutely no comment about why you were rejected. It feels like you sent your music to a magic 8 ball and it just responded “you lose, try again.” But. There are those times where we do receive comments that go along with the rejection; and that’s when we really need to take an honest look at what suggestions have been offered. I will be honest and say that I spent a lot of the first decade of my career dismissing suggestions I was given because they just ‘didn’t understand’ the piece. Yeah, that was dumb.

Look for any constructive criticism that can help you improve. This may come in the form of feedback from a record label or producer, or it may be in the form of a negative review that points out specific areas that need improvement - or even from a performer who played your piece. While it can be tough to hear criticism about your music, try to take it as an opportunity to learn and grow. Look for the nuggets of truth in the criticism and use them to make your music better.

What to keep, and what not to

This is a really tough question to answer. I would say there are kind of three categories of responses to criticism?

What you immediately should dismiss.

Is it constructive? If not, get rid of it. If you implemented that suggestion, would it go against who you are as a composer? If so, dismiss it. Like I said earlier, deciding what to dismiss can be a hard rope to balance on (mostly from youthful arrogance), but over time I think it becomes easier to recognize what you should immediately dismiss.What you should implement right away.

If your comments said something like “violins can’t play this passage,” or, “This notation is unreadable”, or “You forgot to transpose your horn part” (all comments I’ve gotten) - fix those things immediately. These have less to do with your musicality, and are more technical in nature. Always take those as a learning opportunity, and try your hardest to not make those mistakes twice.What you should file away for later.

I think the majority of feedback we get on our music falls in this category. Maybe we didn’t fully understand the suggestion at the time, but after some thought, it was correct. Or, maybe it was a suggestion that you a little uncomfortable hearing, but then thought “what if I did experiment with trying that?” I think a lot more of the comments we receive are applicable to us than we may think at first.

3. What can you do better?

The unpleasant truth is that rejection can be a valuable learning experience. Take some time to reflect on what went wrong and how you can improve for next time. Did you not prepare enough for the audition or interview? Did you not have the right materials or press kit? Did you not research the organization or individual enough before approaching them? If you know of the specific reason for the rejection, use it as a learning opportunity to make sure you're better prepared next time. Of course, sometimes you do everything right and it still doesn’t work out…so for that, refer back to section 1.

An opportunity for Improvement

As artists, our relentless pursuit should be in getting better at our art. Rejection and criticism offers us that very chance. And it gives us a perspective that is very different than our own. Blind spots are notoriously hard to see.

What if your favorite part of the song is the very thing that is making the song not work? You’ve got to be willing to part with it. Cut your best material if it isn’t right for the piece (but don’t throw it away, find some other, better suited spot for it).

Teachability

A lot of it comes down to how teachable you are willing to be. It’s like a parent who insists their child can’t be the problem because their child is perfect. You’re going to miss a lot of opportunities for improvement based on how willing you are to change what needs to be changed, and to learn what needs to be learned.

Practice.

Every musician hears this every single minute of our lives, so I won’t linger here too long. But, yeah. Practice your craft. And I’ll turn the mirror back at me and tell me to practice my craft too.

4. Stay positive

It's easy to get discouraged after being rejected, but it's important to stay positive. Remember that rejection is a part of the music industry, and every successful musician has faced rejection at some point. Use rejection as motivation to work harder and improve your music. Focus on the positive feedback you've received and the progress you've made so far. Remember why you started making music in the first place, and let that passion drive you forward.

The value of your music

Here’s the truth: your music has intrinsic value by the very fact that you saw enough value in it to make it in the first place. And there is an audience for it. I also know how difficult it is - even with how connected we are through the internet - to find that audience. Someone is out there, who upon finding your music will say “wow, I wish I had known about this sooner.”

5. Keep moving forward

Finally, don't let rejection stop you from pursuing your dreams. Keep moving forward and continue to make music. Remember that success in the music industry often comes after many rejections and setbacks. Keep honing your craft and seeking out new opportunities. The more you put yourself out there, the more chances you have of finding success.

Start on the next one.

There’s a great scene in “Tick, Tick Boom” where Jonathan Larson (played by Andrew Garfield) has just had a successful musical workshop, but didn’t receive any offers for his musical to be produced. He asks his agent “what should I do now?” or something to that effect, and she simply responds: “Get to work on the next one.”

Conclusion

Remember first and foremost that rejection is subjective. What one person may reject, another person may embrace. Keep that in mind as you continue to pursue your music career. Don't let rejection define you or your music. Keep creating, keep learning, and keep pushing forward. Eventually, I believe your hard work and perseverance will pay off.

Use rejection as an opportunity to learn and grow, and don't take it personally. Look for constructive criticism, learn from the experience, stay positive, and keep moving forward. With these tips, you can turn rejection into an ally to help you achieve your musical goals.

Starting a New Piece

I thought maybe I would share 3 strategies that helped me overcome writer’s block, and actually start this project.

I’m starting a brand new piece today. I’ve had this idea for a while, but it’s just been sitting in my notebook.

So, I thought maybe I would share 3 strategies that helped me overcome writer’s block, and actually start this project. I’ll be coming at this from a composer’s perspective, but I imagine these strategies probably would transfer to just about any creative endeavor.

1. Start with what you have

What’s in your sketchbook

That stuff you doodle on a napkin

Voice memos you made on your phone

Is there anything you’ve already thought of that can be the basis for your new project?

Are there multiple fragments in your sketchbook that could be combined for this project?

For this piece, I’m starting with a melodic fragment that I found in my notebook (and the concept of “home”, but more on starting with concepts in a little bit). Those little fragments can be expanded to create an entire piece. It does need to be the right fit though, so it’s helpful to have a notebook full of possibilities.

So, If you haven’t already, start a sketchbook/ideas notebook/Voice Memo Catalog. This can be great for starting projects, but it can be especially helpful for all of those times you’re working on something else, but you’ve got a really good but totally unrelated idea.

2. Start with a Story, an Emotion, or a Picture

Sometimes the story comes to me before any music does.

Pick an emotion, any emotion will do. Then brainstorm every single way to evoke that emotion in musical terms. I also like to ask what is the opposite of that emotion, which can give the piece a nice contrast.

Start with a picture in your head: How would you create that scene in music? How would this look in another artform? For example, how would my music look if it was a painting? What would this piece be as a film?

I’ve been pondering different ideas of “home” for a while, and I think that will be the basis for this piece. Perhaps each idea of home can be the basis for each movement, we’ll see. But, having that concept in mind allows me to then think about how to translate that to music.

3. Set a limitation

With literally every possibility sitting before you, it can be extremely intimidating to actually start down a path. All art requires a limitation, or it would never get made. If I just choose the instruments I’ll use, and the length of the piece, I’ve excluded a lot right there, right off the bat. This is really helpful, because you now no longer have to worry about the millions of possibilities you won’t pursue in this project.

I’m starting with cello, and piano, and I want it to be about 10 minutes long.

Take away something. What if you tried to write with no melody? I find this very helpful especially if you tend to do something all the time. I tend to focus too much on melody, so taking it away can really help you focus on other things and come up with something different. You can discover a lot of cool ideas when you are forced to do something different than usual. If you always write in G major with 4/4 time, force yourself to write in anything other than G major 4/4.

Start with a limiting concept. Like a piece built entirely on 3rds. Or, a unique scale to work with. Or, never use C#.

Hopefully, that gave you some piece motivation or inspiration for starting your next project. I should probably stop procrastinating and get back to writing.

Should You Update Your Old Music?

I’m entering year 12 of my composition career. And here’s the thing: a lot of the music I wrote in those first few years is not quite up to my current standards. I’ve improved a lot - which is definitely what you want. A lot of that early music got one or maybe two performances and they’ve kinda just been collecting dust ever since. Or, maybe it’s a song on an early album that receives exactly 2 streams per year.

I was recently asked if I have any works for a particular choir voicing - and I did…but it’s one of those old pieces. I’m not exactly sure I want to hand that piece to an ensemble. We probably all have those moments where we look back on our past work and think: “what was I thinking? Violins don’t even have that note”, “these lyrics sound like they were written by a 3rd grader, and what’s with this guitar part?”, “I don’t even remember writing that”, or, “I’m confident the sopranos hate me for that - and they have every right to”.

That sent me down a rather deep rabbit hole: should I update my old music? Both from a practical and philosophical perspective. Should composers, in general, go back and fix the mistakes of their earlier works? If so, what exactly should they fix? Minor errors? Complete overhauls? All the above?

Today I want to look at the pros and cons of updating your old works, and I’ll let you know what I concluded about updating my own old works.

First let’s look at a few benefits of revisiting and revising your old music:

1. Make an unplayable piece performable.

Pieces that I wrote back in the day on the free version of Finale lacked any sort of regard for whether real life musicians could play that part. If a piece actually made it into the performer’s hands, they would usually tell me if a passage was awkward - or impossible. But that doesn’t mean that we always end up with a smooth, idiomatic part for all of our players, there’s a difference between “playable” and “comfortable”. Once I had a horn passage that was technically in the correct range, but it was the highest part of the range, and it stayed there for quite some time, and I forgot to include any places for the player to breathe. I think the guy’s lips fell off during one rehearsal.

If you’ve got a piece that you like but it has some problems like this, revising it could give the piece new life, or at least a longer life. This is especially important for composers that are self-published as you are your own editor 99% of the time - all mistakes in the score are your fault. And honestly, errors are like whack-a-mole - you take care of one of them and five more pop up in its place.

2. You didn’t have the resources at the time

Maybe you didn’t have the best quality microphone when you recorded it the first time. Maybe your voice has improved. Maybe you’ve gotten better at guitar and so you could record that solo the way you heard it in your head. Maybe you wanted a string quartet, but all you could find was a violin, a clarinet, and a tuba - so you went with that.

Revisiting an old piece can improve the quality of the piece if there are more resources available to you now. If you’ve been dissatisfied with the way a recording or a piece turned out the first time, and you feel like your artistic vision wasn’t fulfilled, this might be a good option.

3. Your artistic vision changed.

Now, this one is perhaps controversial from a philosophical point of view. But if you’re okay with doing a complete overhaul of your work, you might revisit a song because your vision has changed. Maybe you really like the original idea you had, but the execution of it back then is nothing like how you’d do it now. As you grow and evolve as an artist, your creative vision will change, and you can bring your old music in line with your current direction.

On a similar note, I’ve often been curious what it might sound like if some of my favorite artists took their earliest hits and did a “if I wrote this now” version. What if Toto wrote “Africa” today? What would that sound like? Some music (stylistically) is really the product of the time it was written and might not translate well to current styles, but it might be something worth trying with your old stuff.

Drawbacks to updating your old music:

1. It takes time away from new music

With all of these benefits listed above, you do have to consider the price: revising your old music takes time. And if you’re like me, you already find that 24 hours simply is not a long enough day. You’ve got to analyze whether the benefit of revising an old piece outweighs the cost of not working on a new piece.

2. For some, Philosophically, this is like “rewriting history”

For a number of composers, they feel like their entire life’s work should effectively serve as their musical auto-biography. In that sense, it would be like “rewriting” your personal history if you change past works, especially if it was just to bring it in line with your current vision.

And yeah, I kinda see that - if there is a lyric, or a musical moment that came out of a very specific moment in your life - it would change the meaning if you revised the piece.

3. Your fans might not like it.

Certain old music has a particular charm. Many people miss the noise that comes from old vinyls on the new digital music. If you’ve got a piece or a song that is well-loved, it might not be received well if you change it. Not that everything you do has to be to make the fans happy, it’s just something to consider.

Furthermore, you may not like it. You might spend all of this time revising, only to find out you like what you did in the first place better. Sometimes it is hard to capture that magic a second time. But also, it might not be fixable. There’s a profound frustration that festers from trying to resuscitate a piece that is already six feet underground.

So, how much should you revise?

This takes into consideration all of the pros and cons we just talked about. If you go with a “fix the errors” approach, that won’t take nearly as much time as a complete overhaul. I’d also argue that fixing minor errors doesn’t change your past artistic vision.

And if you do decide to revise a piece now, is there a point in the future that you’d want to update it again? Maybe that would be a waste of time…or, maybe it would be a cool series throughout your life to just update the same piece every 10 years or something like that.

Ultimately, it’s up to you. You know your own artistic vision and goals. So, what am I going to do? I’m going to fix enough errors so that all of my previous works are playable, and enjoyable. But, I’ll leave major structural changes in the past. Did I write a low F for a violin? I’ll fix it. Did I incorrectly place syllabic stress in a few places? Those are getting left alone.

I like the work that I’ve done, and I’d like for those pieces to continue. But I also stand by what I wrote back then, even if it isn’t up to my current standards, or what I would have done if I wrote it today.

So, what do you think about revisiting and revising your old music? Let me know in the comments!