Four Questions for Writing Emotion in Music

Music is often emotional, and music often tells stories.

A number of years ago, I noticed that when it came to crafting emotions, and structuring my story for my music - I was usually choosing defaults.

"I'll write a happy song, and it will have 2 verses, 2 choruses, and a bridge." Nothing wrong with that. But, I hadn't intentionally decided whether or not those were the best way to express what I wanted to say.

The first thing I realized was that a good story usually has more than one emotion.

"They were happy, they stayed happy, they lived happily ever after." It's monotonously static. You need more than that for a compelling story.

So, how do we structure our stories, and convey our emotions in a musical way? Here's what I came up with: I ask myself these four questions for every song or piece I write - often before I start writing.

1) Polarity. What is the primary emotion? What is its opposite?

A lot of my music is based not just on two different emotions, but on a contrast of emotions. Emotions don't exactly have concrete opposites (like, Up and Down). Sure, maybe the opposite of Happy is Sad. But what if it is Anger? What if it is Melancholy? It all depends on the story you want to tell. Love can be the opposite of Hate, but it can also be the opposite of Indifference. Asking this question helps me understand the big picture structure of the song.

2) Gravity. Where are we being pulled? What is the force creating the pull?

You could ask this in a musical sense (as in, the leading tone is pulling us to the tonic). But you can also ask this in an emotional sense to help you figure out where your piece wants to go.

3) Journey. What is the emotional journey from start to finish?

If polarity helped me understand the structure from 30,000 feet, Journey is the specific twists and turns the piece took to get there.

There may only be two emotions in the piece - in that case, this is a roadmap of how they interact. But, often there are a lot of emotions, and only two that are primary. Then I need to ask, how do these emotions weave their way into the narrative.

4) Arrival. Where did we end up?

Some composers (and listeners), strongly prefer that the piece end in a logical and expected place. Perhaps that is the most musical choice. "And they all lived happily ever after."

But one thing I like to try is to subvert expectations - try to end the piece with the listener in wonder. Either amazement because they didn't see the ending coming, or, in reflection because I left the ending ambiguous, and it is almost up to the listener to decide how exactly it ended.

Of course, all of this speaks very little to converting emotions into music. That tends to be a highly subjective topic anyway. But, what I'll do with this information after I've done this exercise is to write down every single technique that I can come up with that will convey those emotions using the instruments I have on hand for that piece.

The picture I've attached is from a piece where I wanted to create uncertainty - almost like a fog or a mist; and to the right you can hear how that translated to music.

How do you create emotion in your music? Is it a process like I have just spelled out? Or does yours flow a little more fluidly? Let me know in the comments below.

And if you find this insightful, consider subscribing to my email newsletter:

If you’re looking to learn more about composition and would like to work with me, I’d love to tell you about the different options I’ve got for that. Click here to learn more!

Exploring Take Five's Brilliant Use of 5/4

Take Five is one of the best selling jazz singles of all time. I've always been fascinated by its use of the 5/4 meter. Today we are looking at how the Dave Brubeck Quartet took this simple idea in a complex meter, and made it into a masterpiece.

Take Five is one of the best selling jazz singles of all time. I've always been fascinated by its use of the 5/4 meter. Today we are looking at how the Dave Brubeck Quartet took this simple idea in a complex meter, and made it into a masterpiece.

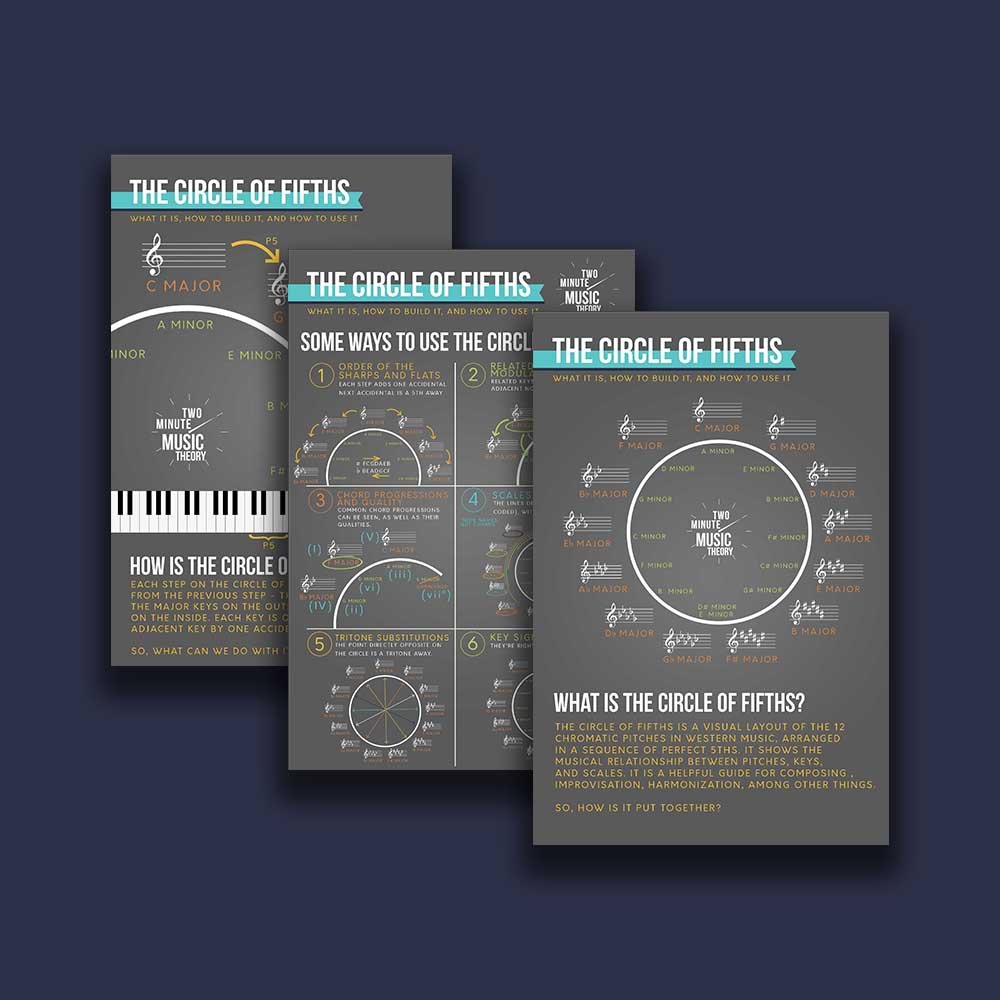

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

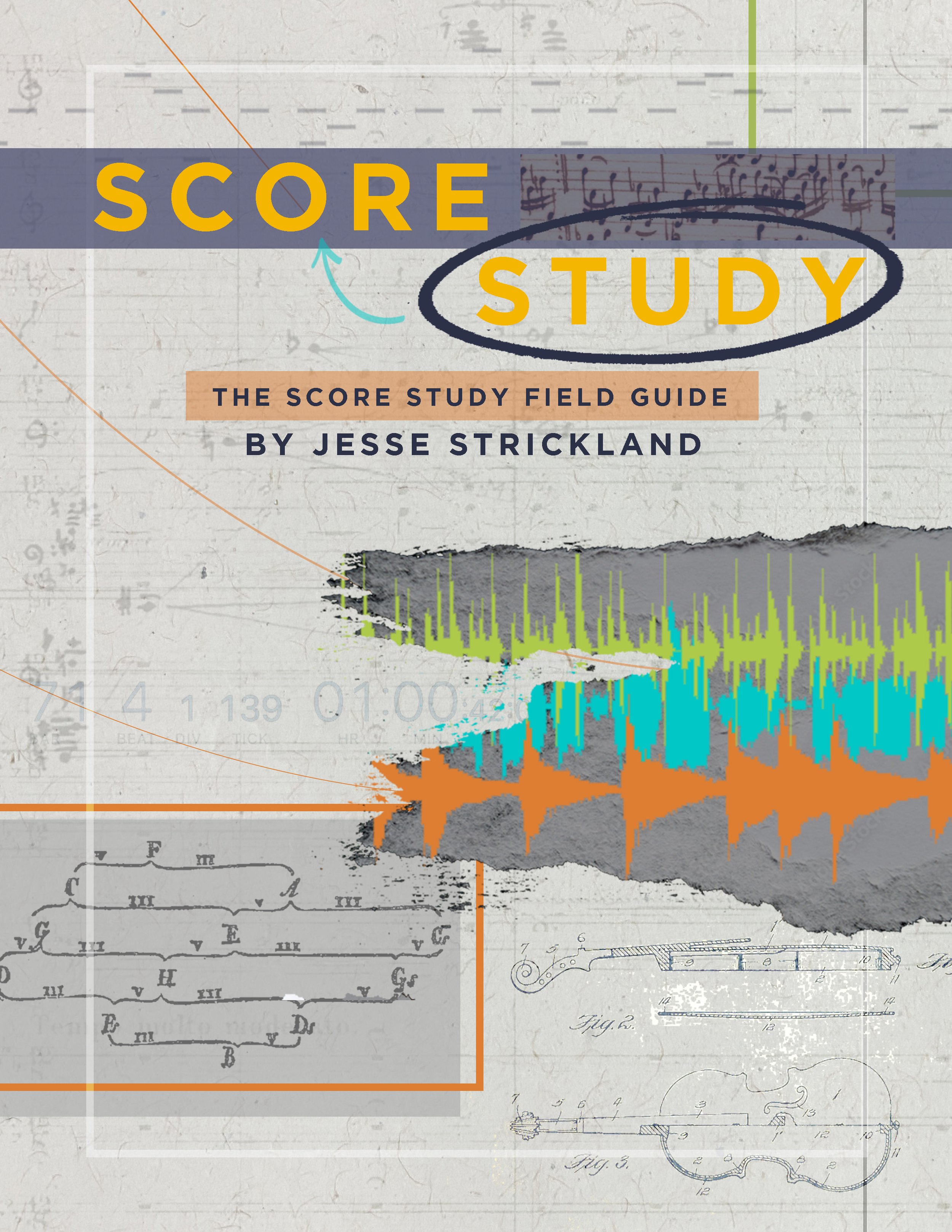

Featured Music Theory Course

Four Things Every New Composer/Songwriter should do

1. Choose Consistency over Quality

Your first compositions aren’t going to be your best. And that’s frustrating - but consistency matters more at this stage. Practice writing a lot - and move on to the next piece. One nice thing about cooking is that it forces you to go through the process and then do it again. You can’t “keep working” on the same grilled cheese sandwich. Cook it, learn from it, try it again. Consistency in the long run will lead to quality.

2. Listen to Music Closely

Really take note of the techniques that other composers are using. Analyze the music, dictate the music, copy the scores by hand, learn to play it on your instrument. This is something else you’ll get better at the more you do it.

3. Listen Widely

I recommend this for any musician, regardless of specialty. Don’t just listen to music in your genre - study across as many genres as you can. You live in a world of infinite genres, let all of them influence your voice.

4. Be Endlessly Curious

Study other arts, ask a lot of questions, experiment constantly, take as many notes as you can, write down everything that comes to your head. I’d wager that every artistic innovation was spurred by curiosity. A lack of curiosity will lead to playing it safe. This is a composer’s best friend, but it is often overlooked. So be curious, and stay curious.

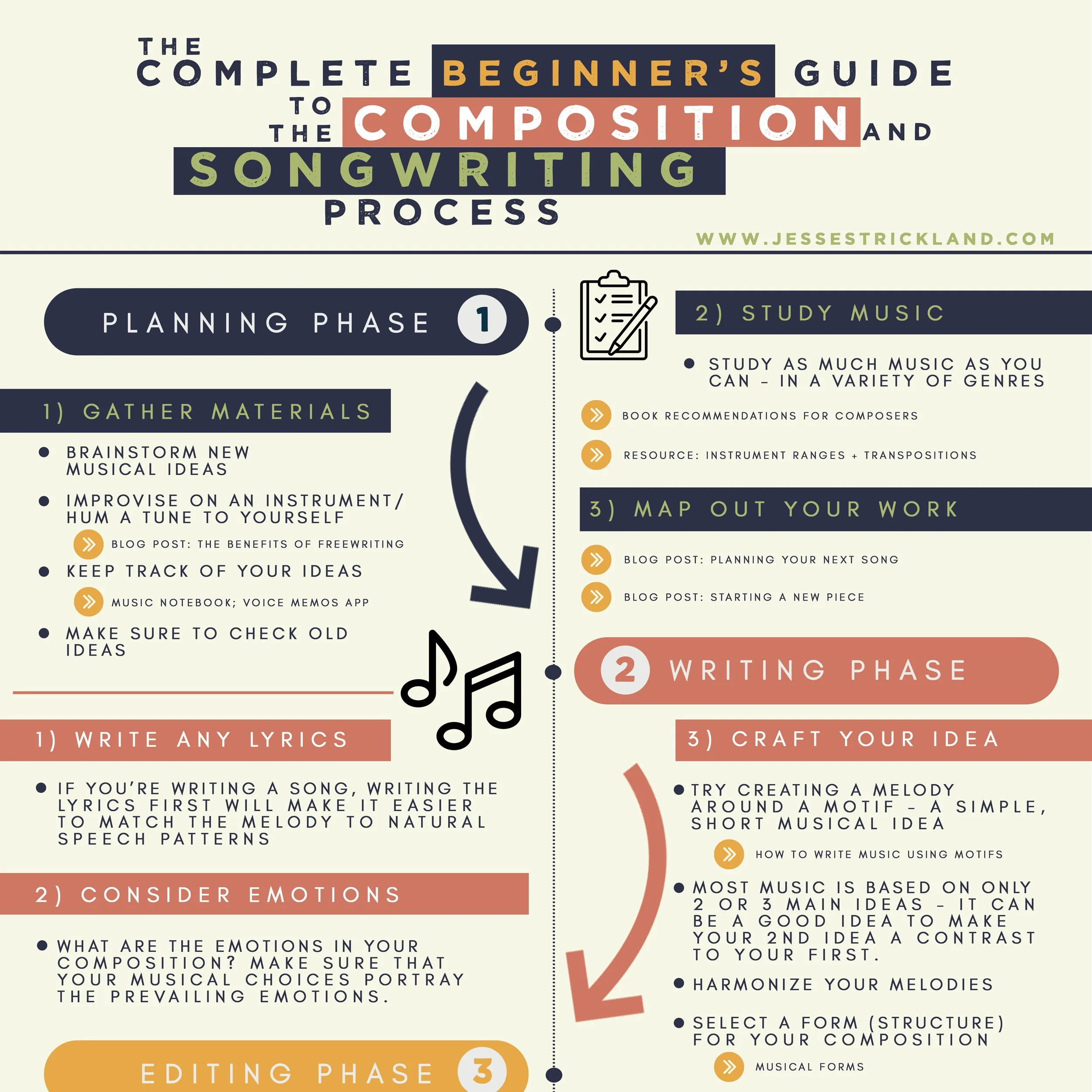

Check out this guide

If you’re new to writing music, I’ve got this free interactive PDF guide to the composition and songwriting process - check it out!

The Art Of Music Theory

Music theory is often confused as being mostly about identification, but really - it's more about interpretation. Music Theory is an art. And it's an artform that is both valuable and practical for all musicians throughout their lifetime.

Music theory is often confused as being mostly about identification, but really - it's more about interpretation. Music Theory is an art. And it's an artform that is both valuable and practical for all musicians throughout their lifetime.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

Introduction to the Composition + Songwriting Process

Why have a Process?

There are a lot of steps and a lot of moving parts when writing a song, or a piece of music. This is why it's really easy to get stuck and frustrated, or even to abandon a project entirely.

It's much easier to accomplish anything if you've got a plan. And for years in my own writing journey, I would constantly get stuck. Whenever I would begin a new piece, things would start off great, until I hit some sort of a wall, and it was like trying to reinvent the wheel every single project. So, I finally had to sit down and write out my personal process for writing a piece of music. Anything that I did that made writing a piece easier, or anything that if I didn't do - I'd have to come back later and do it anyway. Take all of that and put it in a nice linear format, and you've got yourself a bit of an algorithm for writing music.

Of course, it doesn't quite work that nicely. Composition is a messy art. It's not linear, and that's exactly why you need a map. Something you can go back to when you end up lost off the beaten path and unsure which way to go now.

Each and every composer needs their own personal process - we each have a different brain. Our field is an art. This is not a McDonald's, where the goal is to put out an identical product each and every time. We each have our own voice, and our own personality, and our own workflow which produces the results that we want.

However, I think there are four phases to the composition process, regardless of the composer; regardless of the style of music, or era of history.

This is the start of a Five Part series, taking an in-depth look at the composition process. Today, I'll just give an overview of the four phases, and then the next four posts will look at each of them in more detail.

What makes it a composition?

Let's start by defining a composition. There are many ways to write music, and a composition is a specific type of written music. All of the types of written music are valid and good, I'm not trying to elevate one over another, I'm just trying to focus all of us on the same idea. Disclaimer: These are the definitions I'm giving for the sake of this series, other musicians might have varying definitions.

1. A Composition is Original

A composition is a work of music that is new and original to the composer who wrote it. This distinguishes a composition from an arrangement, or a cover. With arrangements and covers, (generally) another composer wrote the source material, and you are just putting your own spin on it. This takes a great deal of skill and consideration, but it's not what I'm talking about in this series. Maybe we'll do a different series on how to do a cover.

So, a composition then, is a work that all of the material is original to the composer (or composers, in the case of a co-write). That's important for our purposes because it gives a composition its own specific process.

2. A Composition is different from an Improvisation

The fact that a composition is planned separates it from an improvisation. You'll often find musicians who have a propensity towards one or the other. I am on the composition side. I have very little ability to improvise. I find that it is very similar to those who can stand up and give a rousing speech of the top of their heads, versus those who do much better to sit down and carefully craft a novel. It's often two separate skill sets.

There's also no editing an improvisation - you know, by definition. Once you've played your saxophone solo, it's over - there's no redo. Of course, once you get into the recording studio with jazz musicians, the line between composition and improvisation starts to blur.

But here we are talking about a planned, crafted, and edited work of music - known as a composition.

One other note: Some might make a distinction between a composer and a songwriter - but I do both and they both have the exact same process for me. So, these four phases apply to both songs and instrumental compositions.

A Free PDF

For this series, I've made an infographic PDF of the entire composition + songwriting process that we're talking about - and it's free when you sign up for my email list. It's also an interactive PDF, so it has links to 16 additional composition resources. You can get your free copy of it here, and follow along as we go the next four posts.

The Four Phases

So what are these four phases? You can break the composition process into the Planning Phase, the Writing Phase, the Editing Phase, and the Transferral Phase.

Planning Phase

Like I mentioned earlier, a composition is planned. Even if you start with a template (say "Verse, Chorus, Verse, Chorus, Bridge, Chorus"), that's still a plan. You're deciding a number of things about the piece before you actually get into the writing of it:

- What's it going to be about?

- What instruments are involved?

- What compositional techniques are you going to use?

- How long will it be?

- What emotions do you want to portray?

And maybe you don't know the answer to some of these things to begin with, but I have found deciding on some of these things before I start writing makes the process go a lot smoother.

The planning phase can look vastly different depending on the style of music. If you're writing film or video game music, the planning phase is very different than a piece that is not written for picture.

Writing Phase

Once you've got a pretty good plan, it's time to start writing. I have found this to be the least linear phase out of the four. I often like to think of the steps in this phase as a checklist rather than a progression. I'll work on a lyric here, a melody there, go back and work on that lyric, then oh, I just had an idea for the B section. It's a rather messy endeavor. This particular section is the place where I get lost most often - but that's why I developed a process. I can always go back and look at the process, and I can also go back and look at the plan I made during the planning phase.

The goal with this phase is to end up with a first draft. I tend to not try to do any fixing during this stage - just get it all out of my head as quickly and as orderly as possible.

Editing Phase

Three main things happen for me in this phase.

1. A music edit. I go back and listen to see what isn't working. A horn part that is not playable. A section where the pacing is too slow. A lyric that's clunky and a little cheesy. A transition that was too abrupt. Those sorts of things

2. Go look for feedback. Composition can be a lonely sport. You've been in your own head the whole time, it's time to bring some other brain into the process.

3. A Notation edit. Unlike the music edit, I'm just looking for things that are out of place in the score this pass. That dynamic marking is in the wrong spot, these two staves are too close to each other. Are my page margins wide enough? Super tedious stuff. Also, something that you may not need to worry about if your goal is to recording.

Transferral Phase

This one might need a different name, but it's the best single word I could find to describe this part of the process.

So we have our final composition - there are typically one of two goals:

1) Record it for audiences to listen to

2) Write it down to hand to players who will perform it for an audience to listen to

Obviously, this particular phase might depend on which style of music you're writing for - as more classical music tends to be the second option, and more popular music tends to be more of the first option.

Of course, there's always that third option where you're going to both write it down, and record it.

The point in all three of these options is that you are taking this idea that was in your head, and you are turning into something that can be understood by another human.

The Series continues...

So, that's a quick overview of the composition process.

Stay tuned for the next four posts where we will look into each of the four phases in detail. Starting with Planning Your Composition.

In the meantime, make sure to get your copy of the Beginner's Guide to the Composition Process.

[FREE] The Complete Beginner's Guide to the Composition Process

Free Interactive pdf guide

One thing I hear from composition students a lot is that the entire process of writing a piece from start to finish is a little overwhelming. I get it. There’s a lot of moving parts. The project has a lot of phases, and each phase has a lot of steps (and sub-steps). Especially for composers with ADHD (like me), it can feel nearly impossible to keep track of.

Maybe you’re a new composer, and you want to get started but how to even go about that is kinda paralyzing.

So, I’ve got a new resource here for you today. It’s an interactive infographic outlining the entire composition process. Each place you find a yellow arrow, there is a link to an additional composition resource that will help guide you on the process.

This resource is free, but it is an exclusive for my email newsletter subscribers. So, if you’d like a copy of it you can subscribe to my newsletter by filling out the form below. I’ll send out new composition resources and tips every week - I think you’ll find it super helpful.

How To Start (Over)

I’m trying to start writing music again - after about 6 months off.

I didn’t mean for it to happen…but sometimes life happens. And I think we have to be okay with that.

It’s an interesting to be working through. It’s not like I’m doing something I don’t like, or even learning something new.

This is a journal entry, of sorts, into my journey of starting over. I’ve got three thoughts that I hope will help you if you are in the same place.

1. Start Small

If you’ve been on an extended hiatus from composing, you might want to just try jumping back into your old routine. Let me tell you from my recent experience - it doesn’t work. It’s like I was a marathon runner and then I did nothing but sit on the couch and eat potato chips for five years…and my first day back I tried to run 20 miles…at my old pace.

Taking a break is fine, a slow start after a break is fine.

So, I’ve been trying to write for 5 minutes a day. Only 5 minutes. Whatever I get done in that time is what I get done. I’m going to stay at 5 minutes until I feel like I can write longer.

As you can imagine, not much can get done in 5 minutes. And that’s okay. But, it didn’t take many days until I had forgotten about time and I was going for 10 - 15 minutes.

So - give yourself the grace to start small.

2. Establish a Writing Routine

Once you’ve gotten back in the habit of showing up every day and writing - establish a writing routine.

Now. A quick caution here. If you had a writing routine before your hiatus, it might not work this time around. Your life situation may have changed, the amount of time you can devote may be smaller. And also, this is just the second step after ‘write for 5 minutes.’ So, establish a writing routine that will facilitate your composing where you are right now.

Establish when and where you will write. How long are these sessions? What do you want to accomplish? Remember to be realistic. Your answer here shouldn’t be: “three hours, and I’m going to write a 30 minute concerto today.” But maybe like, “a 30 minute session where I’ll write the A theme for a solo piano piece”

3. Find a Community

Composition can be a lonely sport. You just sit at your desk, just you and your thoughts. It can be very isolating. You also might have the pervasive thoughts:

“I’m the only one going through this.”

“Maybe I just don’t have it anymore”

“Everything I write is garbage”

I promise, there are other composers are feeling this. (I’d also like to say parenthetically, your identity as a composer isn’t based on productivity) A really good strategy for combatting this is to find a community of musicians and composers who are trying to learn and get better together.

That’s what I’m seeking to create with my new YouTube channel. You can check out more about that here.

There are also a good number of online communities that you could plug into. The /r/composer subreddit is a pretty good one - you can ask all of your questions, ask for feedback on your work, and see that there are others who are in your boat with you.

So, if you’re trying to start over, don’t get discouraged. Try these three things. And remember, it takes time.

Remember why you fell in love with composition in the first place. And just write.

Top 10 Book Recommendations for Composers

One frequent question I get from younger composers is "what books should I read to study composition?" So, I've got my top 10 books that have been foundational for me in my career (both as I was getting started, and even still today).

1. Fundamentals of Composition (Arnold Schoenberg)

2. Theory of Harmony (Schoenberg)

If you know anything about Arnold Schoenberg's music, it might seem odd that I have these books on my list. But, they are simply wonderful books for new composers. He breaks everything down in a very accessible way. No book has impacted how I think about composition more than the "Fundamentals of Composition."

This is the gold standard when it comes to music notation. I cannot recommend this one enough.

As a composer who works with classical ensembles and is also self-published, this book is one of the two books that literally lives on my writing desk. After I was rather embarrassed at a rehearsal where my score and parts were (to be honest) rather unprofessional, I had a professor recommend this book to me. I studied it furiously, and it has made all the difference in my score presentations. If you use staff notation which will be read by performers, this book is pretty much mandatory.

4. Study of Orchestration (Samuel Adler)

The other book that lives on my desk. It was first published in 1982, so some orchestration ideas might not seem as relevant today. But it is comprehensive. It works its way through every family of instruments giving you just about everything you could need to know for writing for that instrument. Note: it is definitely more geared towards writing for those instruments in an orchestral context.

All that being said, I reference this book almost daily. Even if you are a complete beginner to orchestration - this book will be a great guide for you.

5. New Musical Resources (Henry Cowell)

First published in 1930, this book was rather groundbreaking at the time. It explores innovative concepts in both composition and music theory. For the time, many of the approaches to rhythm, harmony, and timbre would have been considered unconventional (like tone clusters, rhythm scales, negative harmony, etc) It really showed the potential of non-traditional instruments and techniques - particularly extended techniques.

While these techniques may seem common now, what I really like about this one it how it encourages composers to break free from conventional musical practices and explore new creative possibilities.

6. 20th Century Harmony (Vincent Persichetti)

The techniques of the 20th century in Western music were quite the departure from traditional techniques. This book gives a great overview of the music theory of the early 20th century. It was published in 1961, so it only covers the music of the first half of the century - namely Schoenberg, Webern, and Berg.

20th Century techniques can be rather confusing to beginners, but this book does a great job of explaining complex topics. Being that the early 20th century laid the foundation for what is currently happening in classical music - this book is highly recommended.

7. Study of Counterpoint and Fugue (Joseph Fux)

An absolute all time classic. If you've ever taken a music theory course and wondered where all of those rules came from - it's probably this book. This is a pedagogical book - meaning it was written for students - and it serves its purpose well. You just need to remember its purpose when reading it. The training in counterpoint that it will give you is a great foundation, and it will give you valuable skills as a composer, even if you don't follow exactly what it says (because if you do, you'll end up sounding like Bach but worse.)

In classical composition training, composers were taught orchestration, and counterpoint; and this book is a great place to go if you want to learn counterpoint.

8. Music of the Lord of the Rings (Doug Adams)

This is my personal favorite of the bunch. Unlike all of the other books, this one is simply an analysis of the soundtrack of the Lord of the Rings trilogy. Apparently, they knew they were on to something good, because during the production process, Doug Adams followed composer Howard Shore around, taking detailed notes about absolutely every single facet of the film's score. The result was nothing short of what I'm sure will prove to be one of the best composition books of the 21st century.

In my estimation, the Lord of the Rings music is by far and away the best film score of all times. So, if you are looking to go into film scoring - you need this book. Study every page of it. But, also if you're a Tolkien nerd - you need this book.

9. Techniques of the Contemporary Composers (David Cope)

This was the first ever composition text I read. I just happened upon it in a public library. At the time, I hadn't received any composition training - I was just eager to learn. So, I read it. And though I didn't fully understand all of it at the time, I was hooked.

"Modern" always lends itself to irony, as this book was published in 1984...and is no longer modern. But it does pick up where the Persichetti book left off, and covers the major composition trends of the later 20th century, namely Minimalism, Aleatoric and chance music, electronic instruments, and microtonality.

10. Choral Arranging (Hawley Ades)

As a primarily choral composer, I have spent a lot of time with this book over the years. I have found that on the whole, many composer who are not choir members themselves are greatly under-educated about writing for choir. And as a choir member, I can tell you it's usually very obvious from their writing when a composer has not sung in a choir themselves.

So, I highly recommend this book if you are a composer who is looking to write for choir in any capacity. It walks you through proper voice leading and voicing, text setting and clarity, even the ranges and registers. Do all of your singers a favor and memorize this book.

Further Reading

The Instrument Transposition Chart I Always Wanted

If you’re a performer, conductor, composer, or music student who has to deal with the headache of transposing instruments - I’ve got a brand new resource for you today.

It’s no surprise that transposing instruments are notoriously difficult to understand. The math of compensation is a bear, and that doesn’t even include the notoriously confusing language that goes along with transposition (“it transposes down a perfect fifth? is that written or sounding? so, I need to go down a fifth? I want to punch whoever came up with this.”)

Not only that - in school, I had to learn the ballpark ranges of every instrument. Here’s the thing, it’s difficult to keep memorized - not to mention, we learned the ranges for professional orchestra players. But in my actual work, I usually write for younger ensembles and I need to know their ranges too. It’s another thing that takes a bunch of time and effort to look up.

For the last decade or so, I’ve been compiling a crude version of this on my desk on various scraps of paper so that I don’t have to endlessly google the answer - or flip through an orchestration textbook - only to have to try to decipher what they mean. Now, I’ve completed this “Instrumental and Vocal Ranges and Transpositions” chart as a comprehensive desk reference guide for all musicians.

The chart is divided by instrument family , with 44 instruments total. For each instrument the chart includes:

Ranges for Beginner, Intermediate, Advanced, and Professional Players

Transpositions for each key, and a direct comparison to the concert pitch

Other notes about writing or reading parts for that instrument

Some great applications for this chart:

Writing and arranging for any ensemble that uses staff notation

Study guide for music students who are first learning about the idea of transposition

Educators who are teaching about transposing instruments

Score study for conductors who are using transposing scores

Analysis for music theorists (or music theory students) who are studying scores

Performers who play transposing instruments - especially younger performers

I think you will find this chart to be a priceless addition to your collection, improving your work flow - it has certainly improved mine.

As an aside, if you’ve been considering enrolling in my beginner composition course “Start Write Now”, this chart is included for free when you enroll. Just saying.

To get your copy of the chart click the link below.

further reading

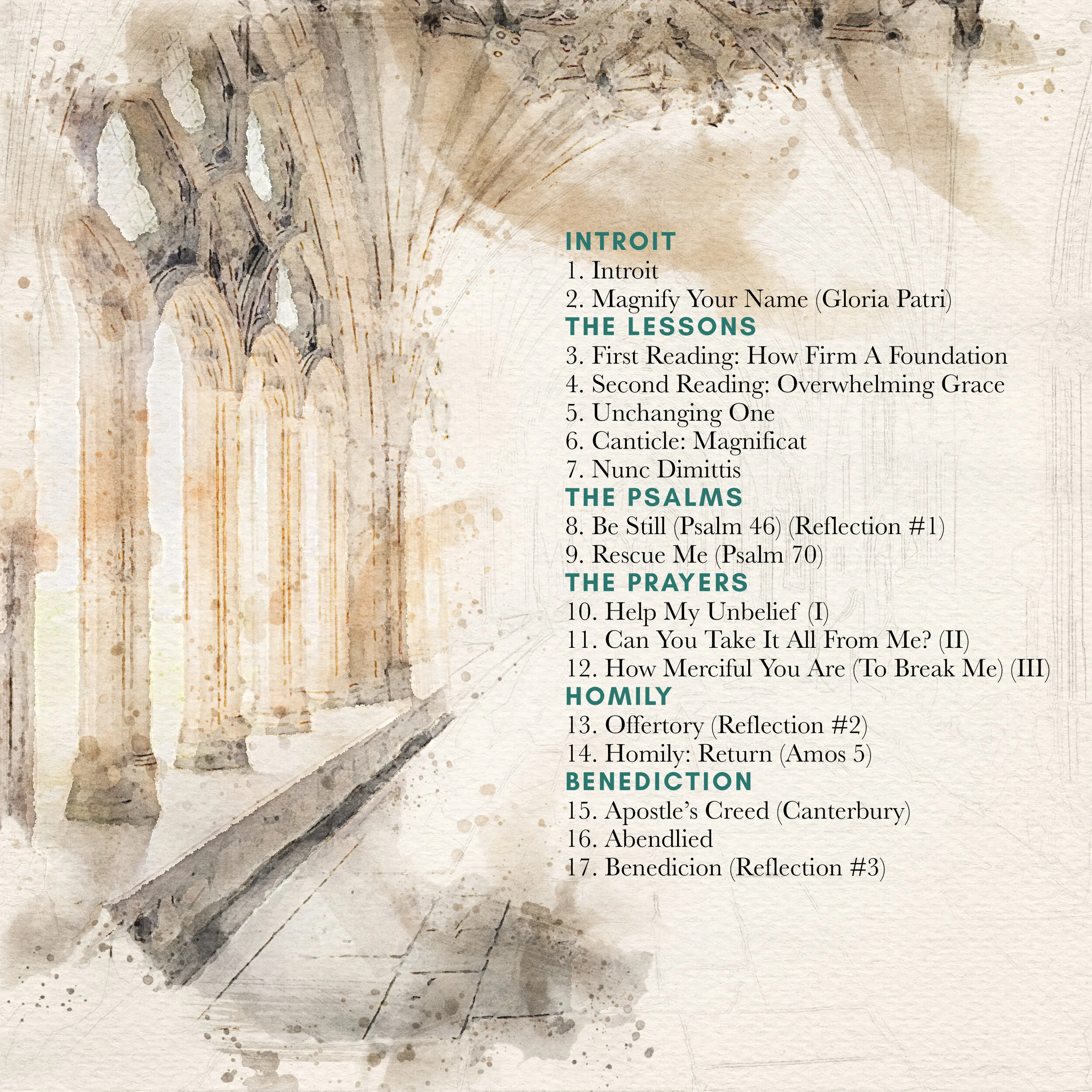

EVENSONG IS HERE

After nearly two years of work, I’m excited to announce that my new album Evensong is here!

Trappist-1: Percussion Quartet No. 1

The official video of my first Percussion Quartet!

The official video for my first Percussion Quartet is live on Facebook! Thanks to my friend Chase Banks and his wonderful team of percussionists for an excellent performance!

The piece itself is called Trappist-1, which refers to a Star System 29 light years from earth. It has 7 planets that all orbit their star closer than Mercury does to the sun. In order for this system to not collapse, the planets orbit each other in a very mathematical way, most of them orbiting their neighbor planet at a ratio of 3:2. In music, the 3:2 ratio is a Perfect 5th, and if you assign the outermost planet as C, then follow the ratios, you end up with a Cmaj9 chord - which is the basis of the piece. In addition, each planet was given a leitmotif, with each motif being proportional to the orbital period of the planet, using musical characteristics that match what we know about each planet. So, go check it out!

Interested in performing this piece? Score and Parts available here.

![[FREE] The Complete Beginner's Guide to the Composition Process](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/588ed41937c5818a6a0b577b/1695052299448-FQ70RDLLDZLJF9XJM5CH/Comp+Infographic+SQ.jpg)