4 Strategies to Finish Your Music Writing Projects

If you are frustrated by unfinished songs and pieces you’re working on: You're not alone. This is one of the most common frustrations I hear from composers, songwriters, and producers that are newer to the music writing. It’s usually one of two things:

1) You’ve written a little something, maybe 8 measures or so, and you can’t figure out where to go next, or, 2) your piece seems disjointed - it's just a random collection of ideas. Both of these will stop progress dead in its tracks.

I feel your pain. I've got a full box of unfinished music sitting in my studio. Here are four strategies that I use to finish my music projects.

1. Overcoming Perfectionism

Perfectionism is one of the biggest roadblocks to finishing music projects. It makes you constantly second-guess your work, leading to endless revisions and even creative paralysis. To combat perfectionism:

Shift Your Mindset: Aim for progress rather than perfection. Understand that no piece of music will ever be flawless, and that’s okay. (would we even like it if it was perfect?)

Set Time Limits: Give yourself a deadline to finish sections of your music. This creates a sense of urgency that can help you move past minor imperfections.

2. Zooming Out for Perspective

Another common issue is getting too caught up in the details, losing sight of the overall structure. If you find yourself obsessing over perfecting every single element without considering the bigger picture, try these steps:

30,000 Feet: Before diving into the details, create a broad outline of your piece. Decide on the overall flow and structure, and then work on the individual sections.

Create a “scale model”: I like to use two tools here: The Short Score, and the Timeline. Both of these allow me to put all of my ideas in physical space. Use these tools to visualize your piece from start to finish. This helps ensure all parts fit together cohesively and prevents well-polished sections from feeling out of place.

Develop and Transition: A huge mistake I see from beginners all of the time is abrupt transitions from one idea to the next. Focus on developing your main ideas and creating smooth transitions between sections to maintain a unified composition.

3. Limiting Your Material

It might seem counterintuitive, but trying to use too much material can be a major roadblock. Many composers feel the need to generate numerous ideas to fill a piece, but this often leads to disjointed music. Instead:

Focus on 1-2 Main Ideas: Most successful pieces are built around a few core themes or motifs. Concentrate on developing these ideas thoroughly.

Development Techniques: Expand, alter, reharmonize, and orchestrate your main ideas to create variety and maintain interest without introducing new material.

Creating Relationships: Ensure that your main ideas relate to each other. Use contrasts in rhythm, dynamics, or register to create a sense of unity and progression.

4. Commit to Consistent Practice

Finishing music requires a commitment to sit down and write regularly. It’s not about finding a magic cure but developing a habit and toolbox to overcome common challenges.

Consistent Practice: Set aside dedicated time for composing and stick to it. Regular practice helps build momentum and keeps you engaged with your work.

Feedback and Revision: Don’t be afraid to seek feedback and make revisions. Use criticism constructively to improve your music and move forward.

This isn’t every single obstacle, but they are the ones I’ve found to be the most common - address these, and you’ll finish more of your music writing projects.

Finish Your Music: A Free Email Course

If you're ready to dive deeper and gain more insights, I’ve written about all of these topics in greater detail in a 5 day email course. It provides practical exercises and detailed strategies to help you overcome these challenges and complete your musical works. It’s completely free, and it will only take about 10-15 minutes per day. These are strategies and exercises that I use in my own writing process - and I think you will find them useful as well.

Enroll Here: https://jesse-strickland.mykajabi.com/finish-more-music-enrollment

Setting Realistic Writing Goals

To be clear:, I’m incredible at setting goals; I’m terrible at setting realistic goals. Maybe you’re there too. We get all of these amazing ideas in our heads.

I’m starting a composition #100daysofpractice or a #100daysofwriting whatever you want to call it - I’d just like to be more consistent. Well, I need a plan of some sort for where I’d like to be at the end of the 100 days (sometime in June) - and that’s where the problem lies. So, I thought “what if a student had asked me that question?” And well, we will see how it goes but here are three things I’ve come up with for setting realistic composition/songwriting goals.

Figure Out Appropriate Pacing

Take a look at your recent writing output. How much have you written over a certain period of time? You can probably expect your output won't be significantly more than that. Perhaps you finished 1 piece/song last month. You're probably not going to suddenly write 10 this month. Set a goal of finishing one piece/song, and if you get to more than that - Great!

If one of your goals is to be able to write more/write faster - then start where you are and work your way up incrementally. You can do this by setting Input Goals: "I will write 30 minutes each day." And if you want to build up incrementally: "Each week, I will add 10 more minutes to my writing time." Of course, all of that depends on your schedule and how much time you can actually devote to writing.

2. Factor in things that are writing adjacent.

I'll often work all day editing a manuscript and then feel like I didn't write at all that day. Which isn't true. These things that are associated with writing are critical parts of the writing process. These are things like Freewriting and Experimentation - where you are just playing around but not actually making progress on a project. Or maybe it's studying the work of another composer for their use of techniques. Or, practicing new techniques on your instrument - or figuring out with players what is physically possible or comfortable. Or perhaps like I mentioned, editing and revisions. All of these things are crucial, but they take time, and we need to factor in those things for setting realistic goals.

3. Set goals that are consistent with your long-term goals.

I have had periods where I wrote what I felt like I was "supposed to" write. If there's no one commissioning you to write a piece, there's no reason to spend time writing a piece you don't want to write. Make sure the things you are doing on a daily basis actually line up with your desired trajectory as a composer and songwriter. What can you write today that will serve as a stepping stone to where you want to go? Don't chase after every opportunity just because it's available. Set goals based on what is going to fulfill you artistically, and what is going to help you in the long run.

So, that's where I am today. Day 1 of 100. I'll be documenting this journey so make sure to follow along from now until June, and we will see where I end up.

How To Start (Over)

I’m trying to start writing music again - after about 6 months off.

I didn’t mean for it to happen…but sometimes life happens. And I think we have to be okay with that.

It’s an interesting to be working through. It’s not like I’m doing something I don’t like, or even learning something new.

This is a journal entry, of sorts, into my journey of starting over. I’ve got three thoughts that I hope will help you if you are in the same place.

1. Start Small

If you’ve been on an extended hiatus from composing, you might want to just try jumping back into your old routine. Let me tell you from my recent experience - it doesn’t work. It’s like I was a marathon runner and then I did nothing but sit on the couch and eat potato chips for five years…and my first day back I tried to run 20 miles…at my old pace.

Taking a break is fine, a slow start after a break is fine.

So, I’ve been trying to write for 5 minutes a day. Only 5 minutes. Whatever I get done in that time is what I get done. I’m going to stay at 5 minutes until I feel like I can write longer.

As you can imagine, not much can get done in 5 minutes. And that’s okay. But, it didn’t take many days until I had forgotten about time and I was going for 10 - 15 minutes.

So - give yourself the grace to start small.

2. Establish a Writing Routine

Once you’ve gotten back in the habit of showing up every day and writing - establish a writing routine.

Now. A quick caution here. If you had a writing routine before your hiatus, it might not work this time around. Your life situation may have changed, the amount of time you can devote may be smaller. And also, this is just the second step after ‘write for 5 minutes.’ So, establish a writing routine that will facilitate your composing where you are right now.

Establish when and where you will write. How long are these sessions? What do you want to accomplish? Remember to be realistic. Your answer here shouldn’t be: “three hours, and I’m going to write a 30 minute concerto today.” But maybe like, “a 30 minute session where I’ll write the A theme for a solo piano piece”

3. Find a Community

Composition can be a lonely sport. You just sit at your desk, just you and your thoughts. It can be very isolating. You also might have the pervasive thoughts:

“I’m the only one going through this.”

“Maybe I just don’t have it anymore”

“Everything I write is garbage”

I promise, there are other composers are feeling this. (I’d also like to say parenthetically, your identity as a composer isn’t based on productivity) A really good strategy for combatting this is to find a community of musicians and composers who are trying to learn and get better together.

That’s what I’m seeking to create with my new YouTube channel. You can check out more about that here.

There are also a good number of online communities that you could plug into. The /r/composer subreddit is a pretty good one - you can ask all of your questions, ask for feedback on your work, and see that there are others who are in your boat with you.

So, if you’re trying to start over, don’t get discouraged. Try these three things. And remember, it takes time.

Remember why you fell in love with composition in the first place. And just write.

Embracing Chaos in the Writing Process

The composition process is not a straightforward process. It's quite messy.

But we often want it to be streamlined and efficient. "If I just do x, y, and z; I'll have a piece of music." It's even more frustrating when we look at other composers, and it seems effortless for them. You hear stories of songwriters that wrote a song in 15 minutes, while you're sitting there dealing with writer's block, and you think there is a problem with you:

"Maybe if I was just a better composer, I wouldn't be struggling with this"

The problem is not your skill level, but your expectations. The chaos in the composition process isn't a flaw, but a feature. The goal isn't to get rid of the mess, but to use that mess to our advantage. After all, you can't make an omelette without breaking a few eggs, right?

Here are three ways that we can embrace the chaos in the composition process.

1. Write What You Know First

Notation Softwares, by their nature, force you into linear writing starting at measure 1.

Recording softwares do as well. When you open up a new project, there is a clear expectation that you are working from left to right, and you need to know what you're doing every single measure.

But that's not always what you know. You may only have a lyric fragment or a motif, and you don't know exactly when you're going to use it. Don't give into the temptation to start at measure 1. Write what you know first, and then work your way out from there.

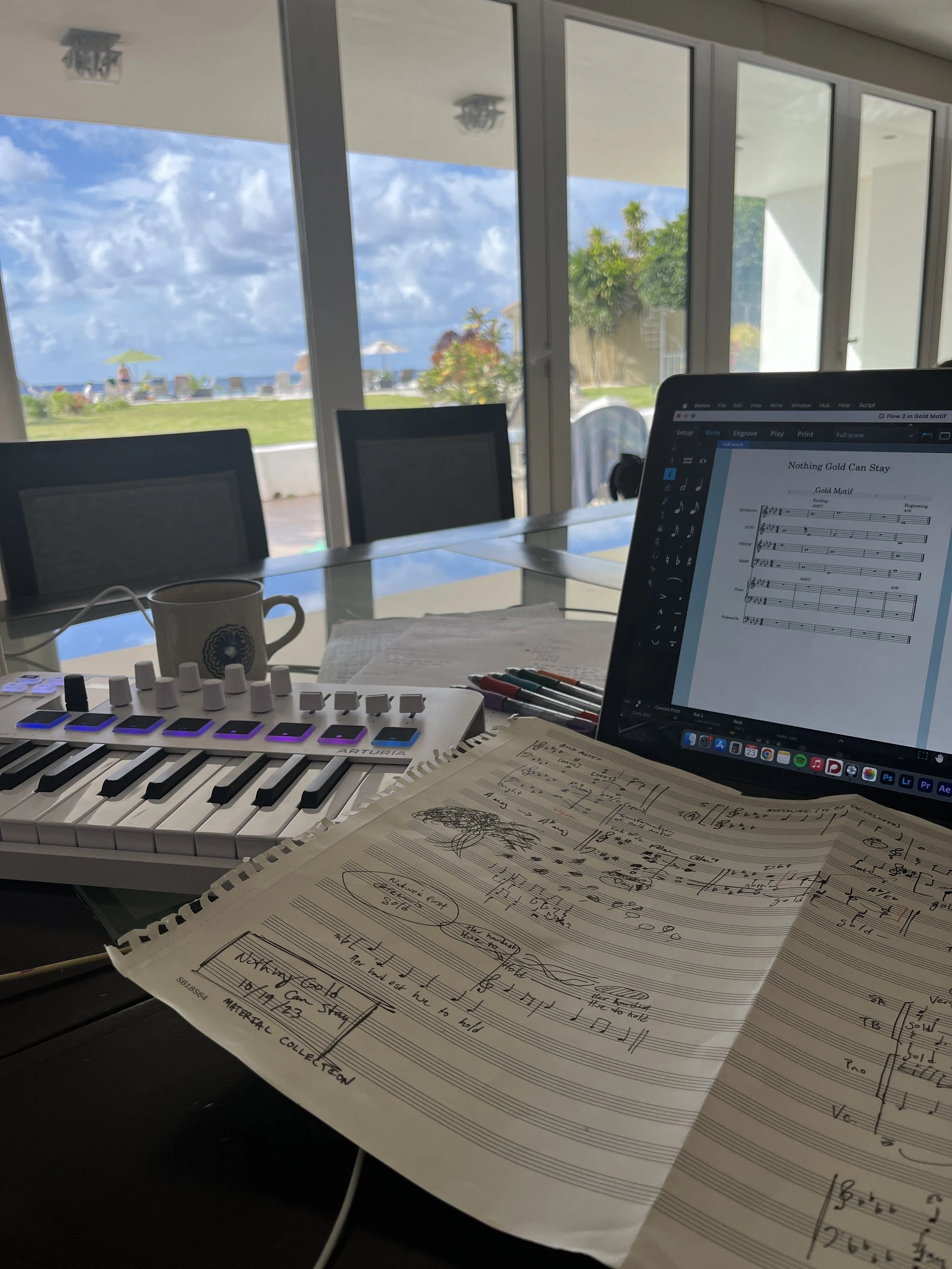

That's one of the reasons I like working on paper - I can work more freely in space. I will either work on large orchestra paper where I can spread out my thoughts, or in a little moleskine notebook that I can carry on the go with me. Both of these options allow me to sketch out ideas without needing to polish them. And they are both helpful when it comes to [starting a new piece].

2. Get To The Double Bar

Speaking of polishing an idea: Don't worry about perfecting any one section - get to the double bar. What do I mean? As quickly as possible, sketch out the entire piece (without having every single answer to every question). Think of this as scaffolding which is set up so that real construction can occur.

Before you start this, it can be nice to have a plan. A rough outline of the structure of the work. I will usually do a timeline before moving on to the short score (where I sketch it out from end to end). Note, with this sketch, I will still work outwards from what I know, filling in the gaps as I figure them out. Still don't feel the pressure to work from left to right.

Don't disrupt the flow of getting your ideas out of your head by tweaking minute details. It's difficult to just let this happen: "what if that idea doesn't make sense? what will the cellos play in that section? How is the voicing of this chord?"

All of this can feel very chaotic - almost like you have no control anymore. But it's a good thing - you are making progress, even if you've made a mess.

3. Let the Piece Tell You Where It Wants to Go

Which brings us to the 3 way to embrace chaos: let the piece tell you where it wants to go.

Your original idea might not be the best for the piece. You've got to be willing to toss out the playbook if the piece tells you it wants to go somewhere else.

There's a saying in writing that you need to be willing to cut your best ideas if it isn't what is best for the project. Even if it's the idea you thought this entire work would be based on.

I once wrote a piece and I wanted this big climax, followed by this one particular chord progression that would be a very soft pianissimo - it's the first idea I had for the piece, and I thought I was working everything else up to this one moment. But, when I actually finished the work and listened to it - I knew immediately, it didn't work. It was really difficult to cut it from the final score - but it was best for the piece.

Often, one of the reasons that the writing process feels chaotic is because we are demanding order where there is none.

further reading

Scaling the Wall: A Composer's Guide to Overcoming Writer's Block

Check out my new eBook!

Even though there’s probably not any hard research on it, I feel pretty confident stating that exactly 100% of composer’s throughout the course of history have experienced Writer’s Block. Put it right there on the list of inevitables with death and taxes.

I know this is a topic on a lot of composer’s minds. Almost every single masterclass or lecture I’ve given to a group of composers, one of the questions at the end is always about dealing with writer’s block. It’s perhaps the question I get asked most often.

I have certainly dealt with it more times than I would like - I feel like my ADHD might impact the frequency. And somehow, each and every time it feels like reinventing the wheel to get out of it. So, for the last few years, I’ve been meticulously documenting exactly what has happened when I fell into writer’s block, what I did to get out of it, and what I did to maintain creativity.

And today, I’m excited to announce that I have compiled all of those strategies into a step-by-step guide, and I’ve put that guide into an eBook for all composer’s to use the next time they inevitably fall into writer’s block.

We’ll look at 1) how to get out of writer’s block, 2) the importance of mental health and creating a healthy relationship with your work, and 3) strategies for maintaining creativity.

All of the things in this eBook are strategies that I personally use in my daily life as a composer, and I think you will find this guide immensely helpful.

So if you are stuck in the pit of writer’s block, desperately looking for a ladder to scale the wall, check out this guide.

Making Rejection Your Ally

For musician of any sort, rejection is a common occurrence…and I’ll be honest, that sucks. Whether it's a rejection letter from a publisher or record label, a negative review from a critic, or not getting the gig you wanted, rejection can be a tough pill to swallow. But rejection doesn't have to be 100% bad. In fact, if you approach it with the right mindset, rejection can be a powerful ally to help you grow as a musician. So, today I want to give some tips I’ve learned on how to deal with rejection and use it to your advantage.

1. Don’t take it personally

First off, remember that it's not personal. I know that’s easier said than done. When you're rejected, it doesn't mean that you're a bad musician or that your music isn't good enough. It simply means that the person or organization that rejected you didn't see a fit for you at this particular time. I understand that doesn’t make it any easier. But. Remember that the music industry is subjective, and what one person likes, another person may not. So don't take rejection as a reflection of your talent or worth as a musician.

This is a rather difficult thing to do. What is more vulnerable than putting your art out into the world? More often than not, It’s not just something you made, but rather it’s a piece of you.

Let’s look at some of the more frequent causes of rejection:

Composition Competitions

Wow, do I have a lot of thoughts on composition competitions. Most of them are not relevant to this discussion so I’ll try to sort through what is pertinent. Each organization who puts together a competition like this probably has a particular sound in mind for the piece they’d like. If not, then you’re looking at dealing with the particular preference of the judges. Neither of these are a reflection on you as a composer.

I love watching cooking competitions. During the judging you’ll hear discrepancies like one judge saying “my meat is overcooked” or “it’s got too much salt for my liking”, and then the next judge will completely disagree with them and say that the dish was executed perfectly. In those moments, it’s hard not to think about composition competitions and the judging that goes on behind the scenes that the composers don’t know about. I have no idea what those judges are looking for - music is a subjective art, not an objective sport. Maybe that judge just wanted a little more chromaticism, a little less polyphony, or any number of other things.

Many of these competitions even require you to take your name off before you submit, so it’s really not personal in those cases. It still feels that way sometimes.

Labels and Publishers

I feel like it’s probably difficult to overstate how many submissions labels and publishers get from musicians on a daily basis.

I once sent in a choir piece to a music publisher that I was rather proud of. The choir who commissioned it had done a spectacular job with the premiere. I was encouraged by the director of that choir to send it to a particular publisher that they had a connection to. After months of waiting, I finally got a response: “This is a beautiful piece! I love it! Unfortunately, we are going to have to pass because we don’t think it will sell all that well.”

Sometimes it’s very obvious that you aren’t the correct fit with a label or a publisher. I’m probably not getting too many record deals by sending my demo off to a heavy metal label - and that doesn’t cause me any pain. It’s when it seems like you would be a good fit, and the executives disagree that this gets hard.

University Music Programs

I’m not even going to pretend that I have even a 1% understanding of the university admissions process. But it’s definitely a common source of rejection among musicians.

Concluding this section: Some composers specifically try to get rejected a certain number of times per year. This does a few things: 1) it’s proof you’re putting yourself out there, 2) gives you a better chance of being accepted for something, and 3) firmly accepts rejection as an unavoidable reality, and in so doing that takes away some of its sting.

2. Look for constructive criticism

Okay, it’s one thing to not take it personally, and just shrug it off, but how can we use that rejection to move forward? One of the worst parts of most rejections letters is that there is absolutely no comment about why you were rejected. It feels like you sent your music to a magic 8 ball and it just responded “you lose, try again.” But. There are those times where we do receive comments that go along with the rejection; and that’s when we really need to take an honest look at what suggestions have been offered. I will be honest and say that I spent a lot of the first decade of my career dismissing suggestions I was given because they just ‘didn’t understand’ the piece. Yeah, that was dumb.

Look for any constructive criticism that can help you improve. This may come in the form of feedback from a record label or producer, or it may be in the form of a negative review that points out specific areas that need improvement - or even from a performer who played your piece. While it can be tough to hear criticism about your music, try to take it as an opportunity to learn and grow. Look for the nuggets of truth in the criticism and use them to make your music better.

What to keep, and what not to

This is a really tough question to answer. I would say there are kind of three categories of responses to criticism?

What you immediately should dismiss.

Is it constructive? If not, get rid of it. If you implemented that suggestion, would it go against who you are as a composer? If so, dismiss it. Like I said earlier, deciding what to dismiss can be a hard rope to balance on (mostly from youthful arrogance), but over time I think it becomes easier to recognize what you should immediately dismiss.What you should implement right away.

If your comments said something like “violins can’t play this passage,” or, “This notation is unreadable”, or “You forgot to transpose your horn part” (all comments I’ve gotten) - fix those things immediately. These have less to do with your musicality, and are more technical in nature. Always take those as a learning opportunity, and try your hardest to not make those mistakes twice.What you should file away for later.

I think the majority of feedback we get on our music falls in this category. Maybe we didn’t fully understand the suggestion at the time, but after some thought, it was correct. Or, maybe it was a suggestion that you a little uncomfortable hearing, but then thought “what if I did experiment with trying that?” I think a lot more of the comments we receive are applicable to us than we may think at first.

3. What can you do better?

The unpleasant truth is that rejection can be a valuable learning experience. Take some time to reflect on what went wrong and how you can improve for next time. Did you not prepare enough for the audition or interview? Did you not have the right materials or press kit? Did you not research the organization or individual enough before approaching them? If you know of the specific reason for the rejection, use it as a learning opportunity to make sure you're better prepared next time. Of course, sometimes you do everything right and it still doesn’t work out…so for that, refer back to section 1.

An opportunity for Improvement

As artists, our relentless pursuit should be in getting better at our art. Rejection and criticism offers us that very chance. And it gives us a perspective that is very different than our own. Blind spots are notoriously hard to see.

What if your favorite part of the song is the very thing that is making the song not work? You’ve got to be willing to part with it. Cut your best material if it isn’t right for the piece (but don’t throw it away, find some other, better suited spot for it).

Teachability

A lot of it comes down to how teachable you are willing to be. It’s like a parent who insists their child can’t be the problem because their child is perfect. You’re going to miss a lot of opportunities for improvement based on how willing you are to change what needs to be changed, and to learn what needs to be learned.

Practice.

Every musician hears this every single minute of our lives, so I won’t linger here too long. But, yeah. Practice your craft. And I’ll turn the mirror back at me and tell me to practice my craft too.

4. Stay positive

It's easy to get discouraged after being rejected, but it's important to stay positive. Remember that rejection is a part of the music industry, and every successful musician has faced rejection at some point. Use rejection as motivation to work harder and improve your music. Focus on the positive feedback you've received and the progress you've made so far. Remember why you started making music in the first place, and let that passion drive you forward.

The value of your music

Here’s the truth: your music has intrinsic value by the very fact that you saw enough value in it to make it in the first place. And there is an audience for it. I also know how difficult it is - even with how connected we are through the internet - to find that audience. Someone is out there, who upon finding your music will say “wow, I wish I had known about this sooner.”

5. Keep moving forward

Finally, don't let rejection stop you from pursuing your dreams. Keep moving forward and continue to make music. Remember that success in the music industry often comes after many rejections and setbacks. Keep honing your craft and seeking out new opportunities. The more you put yourself out there, the more chances you have of finding success.

Start on the next one.

There’s a great scene in “Tick, Tick Boom” where Jonathan Larson (played by Andrew Garfield) has just had a successful musical workshop, but didn’t receive any offers for his musical to be produced. He asks his agent “what should I do now?” or something to that effect, and she simply responds: “Get to work on the next one.”

Conclusion

Remember first and foremost that rejection is subjective. What one person may reject, another person may embrace. Keep that in mind as you continue to pursue your music career. Don't let rejection define you or your music. Keep creating, keep learning, and keep pushing forward. Eventually, I believe your hard work and perseverance will pay off.

Use rejection as an opportunity to learn and grow, and don't take it personally. Look for constructive criticism, learn from the experience, stay positive, and keep moving forward. With these tips, you can turn rejection into an ally to help you achieve your musical goals.