Which Notation Software Should I Use?

For any composer/arranger/songwriter who uses staff notation for either writing or performing, you'll more than likely need a notation software. Maybe you want to write it out by hand, but I don't recommend it. It will obvious look much cleaner, and more professional to have your music engraved by a notation software.

How do you know which one to use? Pretty much all of them claim to be the best software on the market. With a multitude of notation software options available today, each boasting its own set of features and quirks, it's natural to feel a little overwhelmed when trying to pick the best one for your needs. Today I'll attempt to guide you through the labyrinth of musical notation software.

Most of the notation software options available have both a free and a pro version - obviously with the free version having less capabilities than its premium counterpart. Which one you need will be dependent on which capabilities you need your notation software to have. Also note that many of these software have some sort of Education Discount.

Noteflight

Noteflight Basic

This is an online software that I would recommend if you have been given a composition assignment in a class and need a free notation software. Very user friendly even for beginners, and it has plenty of features, but you are limited to 10 scores in the free version. So, if you only need it for somewhere between 1 and 10 projects - you're gold.

Noteflight Premium

But, I'm going to bet in the process of creating your first 10 scores, you get really hooked on this whole music writing thing, and you'll want to make more. You can upgrade to Noteflight Premium for either a monthly or a yearly subscription. Premium is where Noteflight really shines. You'll have access to all of the notation input features, but also access to over 80,000 digital scores that are in the Hal Leonard collection. While I think this is a good choice for all composers - it's probably the best choice for those who are looking to do mostly arrangements because of the access to the Hal Leonard catalog. Noteflight also has a great collaboration feature, making it a good choice for ensembles.

Not only that but you've got access to the ArrangeMe platform - Hal Leonard's platform for selling arrangements. If you work with arrangements, you know how difficult it is to jump through all of those legal hoops. Here, most of that is taken care of for you.

Conclusion: Best Choice for Arrangers, A Cappella Ensembles, and Educational Use

Dorico

Dorico SE

This is Dorico's free version. You are not limited by printing or number of scores, but you are pretty limited in terms of the customization (which in my opinion, is what makes Dorico stand out). Many of the options are fixed for you, and you are limited to 8 instruments on any given project.

Dorico Pro

A friend of mine in grad school was a beta tester for Dorico and he introduced me to it, and I was instantly hooked. I originally switched to Dorico because of its capabilities with microtonal accidentals. It has the ability to do most anything you can imagine for staff notation. In my opinion, this software is the most intuitive and user friendly. The amount of customization that you can do with Dorico is almost inexhaustible. I recommend this for higher education and professional composers who specifically need advanced features from their notation software (ie, microtonality, etc). This software is a one time payment (until you want to upgrade). This is my every day notation software, and my performers have always been thrilled with the clarity of the final scores.

Dorico also has a great capability for scoring to picture. So, if you are a film or TV composer (or, are pursuing that path) this might be the software you need. I personally don't do any scoring for picture, so I can't fully speak to its full potential there.

Dorico is from the same developers as Cubase, which makes them rather compatible, if you have Cubase as your recording software.

Conclusion: Best Choice for professional composers, film and tv composers

Sibelius

I don't really have anything good to say about Sibelius. In all of my experience with the software, it's glitchy, it constantly crashes, it's not terribly intuitive, and it hasn't really improved with new software updates. It's also got a pretty high price tag. Anyone who has ever used Sibelius probably has trauma related to a “Sibelius has unexpected stopped working” error.

That being said, it's been around for quite some time and at one point was likely the most popular. I know there are a lot of professional composers who still have Sibelius as their primary software. So, this is just my experience with Sibelius - your results may vary.

One other thing: it is from the same developers as ProTools - so the two are fully integrated. So, if you use that as your recording software, you might give this a try.

Conclusion: Choose something else

Finale

This was my first notation software. I found a free version of it way back in like 2005 or something. I used it for over a decade until I switched to Dorico. It's fairly easy to use, but it has a moderate learning curve. I wrote my first major work using Finale, and it was fine. Their website make it sound like it's a way better software than it is.

For years, Finale and Sibelius were like your only two choices - so a lot of professional composers are still Finale users. It has all of the features you're probably going to need.

My biggest complaint with Finale is 1) sometimes you can make a small change and it will completely destroy all of your formatting (like Microsoft Word does sometimes), and 2) it doesn't always make the best decisions when it comes to notation layout. I have spent hours fixing mistakes that Finale made when I input something. You've really got to know your notation standards to know what is correct.

It is much cheaper than Dorico and Sibelius, and it has a good educational price point. So, if you end up learning Finale because it's what is in your school's computer lab, you might just end up sticking with Finale.

Conclusion: If your choice is Sibelius or Finale, choose Finale.

MuseScore

According to its website, it's the most popular notation software - perhaps because it is the only one on this list that is entirely free. All of the capabilities of MuseScore come without cost, it's a free download, and a great software. For the price, the playback instruments in its latest version are incredible (just go look some up on YouTube). This is a great no-risk software for new composers who are trying everything out. If you decide composition isn't for you, you haven't lost anything. But, even if you keep going, MuseScore probably has most everything you'll need. However, I have found for me personally, I don't like the user interface as much (even though it has GREATLY improved from its previous versions)

It's also Open Source, so it's always improving, and you don't have to wait years for a software update. It is very easy to share your music, and have your music found by others.

Conclusion: Best Choice for brand new composers, hobbyist composers

Final Thoughts

To wrap all of this up - you can honestly use any of these softwares successfully.

Consider these factors:

- Price you're willing to invest

- Specific capabilities you need

- The user interface that you find the easiest/most natural

- Sharing functionality that suits you

Perhaps you'll even have to weigh which of these factors are most important (give up some functionality for a lower price, etc.). It's likely that all of these have a free trial, so I do recommend trying each of them out and seeing which one you like the most. At the end of the day, the best software is one that is capable of getting your musical vision in writing in a way that the performers will best understand, and won't cost you your sanity in the process.

One last question: Do I actually need a notation software?

For any composer/arranger/songwriter who uses staff notation for either writing or performing: Yes, you'll more than likely need a notation software. However, not every musician uses staff notation. Maybe chord charts or lead sheets is more common in your genre. Don't feel like you have to use staff notation to be a musician. In that case, you probably don't need a notation software - you might be better served by a recording software.

From the Microphone to the Computer - Essential Recording Gear For Composers, Part 2

We're talking about all of the gear you'll need to have a home studio as a composer by walking step-by-step through the recording signal flow chain. Last time we looked at finding the right microphone. Here’s an overview of the two-part series:

From the Microphone to the Computer

So, in the microphone phase, we took actual sound waves and we converted them into an electrical signal - that's still analog.

At this point in the recording process, you have the opportunity to include any outboard effects hardware, such as a compressor or an EQ...but if you know what to do with those, you're likely not reading this blog post. And if you don't know what you're doing with those, then you can skip this phase.

Digital Converters and Audio Interfaces

Now we need to get the system out of analog. We need to convert it to digital in order to get it into a computer for us to edit. We can do that with a device called an analog to digital converter. What the name lacks in creativity it makes up for in clarity.

After that we need a device called an audio interface. If you aren't familiar with the word interface, it is the border between two things - it's going to allow our audio signal to pass the border into a recording software.

In a lot of studio setups, these are two separate devices. But lucky for you, there are plenty of 2-in-1 devices that are both Analog to digital converters and audio interfaces. Perhaps the most popular one on the market right now is the Focusrite Scarlett Solo, and its big brother the 2i2.

These are incredible good for their price point, and are great for those who don't have a large studio operation. The Solo has one xlr input and one 1/4" input - like for your vocals and a guitar, as if you were playing...well, Solo. The 2i2 has the option for either two xlrs, two 1/4" inputs, or one of each, giving you a little more flexibility (particularly if you wanted to record a stereo pair).

Note: As of the publishing of this blog, a bundle including the Focusrite Solo, a pair of decent headphones, and the Blue Spark Microphone is available and a great choice.

Digital Audio Workstation

At the point your signal passes through the audio interface you can work with that signal in a DAW: a Digital Audio Workstation, or recording software. I was originally going to do a third post looking at which is the best for composers, but this post here says it much better than I could.

TL;DR - Garageband is free if you’ve got a Mac. Logic is the pro version (and the one I use). Pro Tools is great for PC and those with a large studio. Ableton is best at live. FL studio is best at loop based compositions. Audacity is free, but has limited capabilities (can be great for podcasts.) Cubase is great at virtual instruments (and also very compatible with Dorico, make sure to check out “Which Notation Software Should I Use?”)

Monitoring

But, you don't just want your audio in the computer, you need to be able to hear it.

For that, the signal has to be sent back through the audio interface and converted back into an analog sound.

Speaker Cables

Your audio interface will have the ports for some speaker cables - usually one for left, and one for right. You'll want to make sure that the cable you purchase is distinctly a speaker cable. Despite its 1/4" end, the speaker cable and instrument cable are NOT the same thing. You will introduce noise to your recording at best, and damage your equipment at worst. So, make sure you've got some actual speaker cables.

Studio Monitors

I'll be delicate here, as this can spark endless debate among enthusiasts. You need a set of speakers to listen to playback, and effectively mix your recording. The types and sizes of this are quite varied, and the price points are quite varied as well.

The size of your speaker should match the size of your room. In general, for a small to medium-sized home studio, 5-inch or 6-inch nearfield (because you are near the speaker) studio monitors are often a good starting point. They provide a balanced sound and are suitable for various music production tasks.

Your budget will also play a significant role in speaker selection. High-quality studio monitors can be expensive, but there are also budget-friendly options available that provide good sound quality for home studios. I'll list three that I have used in my studio.

One other thing to consider: the type of music you produce can influence your speaker choice. If you're primarily working on bass-heavy electronic music, you may need larger speakers with good low-frequency response (perhaps even a subwoofer). If you're recording acoustic instruments or vocals, smaller monitors with accurate mids and highs might suffice.

Headphones

There are a lot of reasons you might want a good set of headphones for your home studio. From audio editing on the road to hearing reference tracks as you (or someone else) records a new track.

I'm fairly certain you know what a pair of headphones does. And much like the speakers, you can spend a wide range of money, and preferences can start internet wars.

Different headphones have different frequency responses, meaning that they will interpret your mix accordingly. You will want to consider your purpose for your headphones - do you want to accurately mix your music, or are you mostly using them as a reference? You'll want a higher fidelity headphone if you're going to do mixing. The Audio-Technica ATH-M20X is a good budget choice here, giving a decent sound at a good price. For a little more, the Audio-Technica ATH-M50x is one of my favorites. A friend of mine is an evangelist for the Sony MDR-7506, and I feel like he'd appreciate me mentioning them here.

If you are recording multiple musicians at once, and they all need headphones, you'll want a headphone amp and splitter. I've always loved the Behringer MicroAMP HA400 4-ch Headphone Amp - inexpensive and reliable.

Top 10 Book Recommendations for Composers

One frequent question I get from younger composers is "what books should I read to study composition?" So, I've got my top 10 books that have been foundational for me in my career (both as I was getting started, and even still today).

1. Fundamentals of Composition (Arnold Schoenberg)

2. Theory of Harmony (Schoenberg)

If you know anything about Arnold Schoenberg's music, it might seem odd that I have these books on my list. But, they are simply wonderful books for new composers. He breaks everything down in a very accessible way. No book has impacted how I think about composition more than the "Fundamentals of Composition."

This is the gold standard when it comes to music notation. I cannot recommend this one enough.

As a composer who works with classical ensembles and is also self-published, this book is one of the two books that literally lives on my writing desk. After I was rather embarrassed at a rehearsal where my score and parts were (to be honest) rather unprofessional, I had a professor recommend this book to me. I studied it furiously, and it has made all the difference in my score presentations. If you use staff notation which will be read by performers, this book is pretty much mandatory.

4. Study of Orchestration (Samuel Adler)

The other book that lives on my desk. It was first published in 1982, so some orchestration ideas might not seem as relevant today. But it is comprehensive. It works its way through every family of instruments giving you just about everything you could need to know for writing for that instrument. Note: it is definitely more geared towards writing for those instruments in an orchestral context.

All that being said, I reference this book almost daily. Even if you are a complete beginner to orchestration - this book will be a great guide for you.

5. New Musical Resources (Henry Cowell)

First published in 1930, this book was rather groundbreaking at the time. It explores innovative concepts in both composition and music theory. For the time, many of the approaches to rhythm, harmony, and timbre would have been considered unconventional (like tone clusters, rhythm scales, negative harmony, etc) It really showed the potential of non-traditional instruments and techniques - particularly extended techniques.

While these techniques may seem common now, what I really like about this one it how it encourages composers to break free from conventional musical practices and explore new creative possibilities.

6. 20th Century Harmony (Vincent Persichetti)

The techniques of the 20th century in Western music were quite the departure from traditional techniques. This book gives a great overview of the music theory of the early 20th century. It was published in 1961, so it only covers the music of the first half of the century - namely Schoenberg, Webern, and Berg.

20th Century techniques can be rather confusing to beginners, but this book does a great job of explaining complex topics. Being that the early 20th century laid the foundation for what is currently happening in classical music - this book is highly recommended.

7. Study of Counterpoint and Fugue (Joseph Fux)

An absolute all time classic. If you've ever taken a music theory course and wondered where all of those rules came from - it's probably this book. This is a pedagogical book - meaning it was written for students - and it serves its purpose well. You just need to remember its purpose when reading it. The training in counterpoint that it will give you is a great foundation, and it will give you valuable skills as a composer, even if you don't follow exactly what it says (because if you do, you'll end up sounding like Bach but worse.)

In classical composition training, composers were taught orchestration, and counterpoint; and this book is a great place to go if you want to learn counterpoint.

8. Music of the Lord of the Rings (Doug Adams)

This is my personal favorite of the bunch. Unlike all of the other books, this one is simply an analysis of the soundtrack of the Lord of the Rings trilogy. Apparently, they knew they were on to something good, because during the production process, Doug Adams followed composer Howard Shore around, taking detailed notes about absolutely every single facet of the film's score. The result was nothing short of what I'm sure will prove to be one of the best composition books of the 21st century.

In my estimation, the Lord of the Rings music is by far and away the best film score of all times. So, if you are looking to go into film scoring - you need this book. Study every page of it. But, also if you're a Tolkien nerd - you need this book.

9. Techniques of the Contemporary Composers (David Cope)

This was the first ever composition text I read. I just happened upon it in a public library. At the time, I hadn't received any composition training - I was just eager to learn. So, I read it. And though I didn't fully understand all of it at the time, I was hooked.

"Modern" always lends itself to irony, as this book was published in 1984...and is no longer modern. But it does pick up where the Persichetti book left off, and covers the major composition trends of the later 20th century, namely Minimalism, Aleatoric and chance music, electronic instruments, and microtonality.

10. Choral Arranging (Hawley Ades)

As a primarily choral composer, I have spent a lot of time with this book over the years. I have found that on the whole, many composer who are not choir members themselves are greatly under-educated about writing for choir. And as a choir member, I can tell you it's usually very obvious from their writing when a composer has not sung in a choir themselves.

So, I highly recommend this book if you are a composer who is looking to write for choir in any capacity. It walks you through proper voice leading and voicing, text setting and clarity, even the ranges and registers. Do all of your singers a favor and memorize this book.

Further Reading

Embracing Chaos in the Writing Process

The composition process is not a straightforward process. It's quite messy.

But we often want it to be streamlined and efficient. "If I just do x, y, and z; I'll have a piece of music." It's even more frustrating when we look at other composers, and it seems effortless for them. You hear stories of songwriters that wrote a song in 15 minutes, while you're sitting there dealing with writer's block, and you think there is a problem with you:

"Maybe if I was just a better composer, I wouldn't be struggling with this"

The problem is not your skill level, but your expectations. The chaos in the composition process isn't a flaw, but a feature. The goal isn't to get rid of the mess, but to use that mess to our advantage. After all, you can't make an omelette without breaking a few eggs, right?

Here are three ways that we can embrace the chaos in the composition process.

1. Write What You Know First

Notation Softwares, by their nature, force you into linear writing starting at measure 1.

Recording softwares do as well. When you open up a new project, there is a clear expectation that you are working from left to right, and you need to know what you're doing every single measure.

But that's not always what you know. You may only have a lyric fragment or a motif, and you don't know exactly when you're going to use it. Don't give into the temptation to start at measure 1. Write what you know first, and then work your way out from there.

That's one of the reasons I like working on paper - I can work more freely in space. I will either work on large orchestra paper where I can spread out my thoughts, or in a little moleskine notebook that I can carry on the go with me. Both of these options allow me to sketch out ideas without needing to polish them. And they are both helpful when it comes to [starting a new piece].

2. Get To The Double Bar

Speaking of polishing an idea: Don't worry about perfecting any one section - get to the double bar. What do I mean? As quickly as possible, sketch out the entire piece (without having every single answer to every question). Think of this as scaffolding which is set up so that real construction can occur.

Before you start this, it can be nice to have a plan. A rough outline of the structure of the work. I will usually do a timeline before moving on to the short score (where I sketch it out from end to end). Note, with this sketch, I will still work outwards from what I know, filling in the gaps as I figure them out. Still don't feel the pressure to work from left to right.

Don't disrupt the flow of getting your ideas out of your head by tweaking minute details. It's difficult to just let this happen: "what if that idea doesn't make sense? what will the cellos play in that section? How is the voicing of this chord?"

All of this can feel very chaotic - almost like you have no control anymore. But it's a good thing - you are making progress, even if you've made a mess.

3. Let the Piece Tell You Where It Wants to Go

Which brings us to the 3 way to embrace chaos: let the piece tell you where it wants to go.

Your original idea might not be the best for the piece. You've got to be willing to toss out the playbook if the piece tells you it wants to go somewhere else.

There's a saying in writing that you need to be willing to cut your best ideas if it isn't what is best for the project. Even if it's the idea you thought this entire work would be based on.

I once wrote a piece and I wanted this big climax, followed by this one particular chord progression that would be a very soft pianissimo - it's the first idea I had for the piece, and I thought I was working everything else up to this one moment. But, when I actually finished the work and listened to it - I knew immediately, it didn't work. It was really difficult to cut it from the final score - but it was best for the piece.

Often, one of the reasons that the writing process feels chaotic is because we are demanding order where there is none.

further reading

The Instrument Transposition Chart I Always Wanted

If you’re a performer, conductor, composer, or music student who has to deal with the headache of transposing instruments - I’ve got a brand new resource for you today.

It’s no surprise that transposing instruments are notoriously difficult to understand. The math of compensation is a bear, and that doesn’t even include the notoriously confusing language that goes along with transposition (“it transposes down a perfect fifth? is that written or sounding? so, I need to go down a fifth? I want to punch whoever came up with this.”)

Not only that - in school, I had to learn the ballpark ranges of every instrument. Here’s the thing, it’s difficult to keep memorized - not to mention, we learned the ranges for professional orchestra players. But in my actual work, I usually write for younger ensembles and I need to know their ranges too. It’s another thing that takes a bunch of time and effort to look up.

For the last decade or so, I’ve been compiling a crude version of this on my desk on various scraps of paper so that I don’t have to endlessly google the answer - or flip through an orchestration textbook - only to have to try to decipher what they mean. Now, I’ve completed this “Instrumental and Vocal Ranges and Transpositions” chart as a comprehensive desk reference guide for all musicians.

The chart is divided by instrument family , with 44 instruments total. For each instrument the chart includes:

Ranges for Beginner, Intermediate, Advanced, and Professional Players

Transpositions for each key, and a direct comparison to the concert pitch

Other notes about writing or reading parts for that instrument

Some great applications for this chart:

Writing and arranging for any ensemble that uses staff notation

Study guide for music students who are first learning about the idea of transposition

Educators who are teaching about transposing instruments

Score study for conductors who are using transposing scores

Analysis for music theorists (or music theory students) who are studying scores

Performers who play transposing instruments - especially younger performers

I think you will find this chart to be a priceless addition to your collection, improving your work flow - it has certainly improved mine.

As an aside, if you’ve been considering enrolling in my beginner composition course “Start Write Now”, this chart is included for free when you enroll. Just saying.

To get your copy of the chart click the link below.

further reading

Finding the Right Microphone - Essential Recording Gear For Composers, Part 1

Whether it's recording albums (or just demos), to creating mockups of instrumental works - it's pretty much mandatory for composers to have a functioning home recording studio.

If you're just starting out, all of this may seem overwhelming - after all, you just wanted to write music. So today I'm starting a two-part series where we're breaking down everything essential you'll need to get started.

I'm going to structure this by signal flow - that is the process that a sound takes from its place in the real world to its place in the recording software.

Finding the Right Microphone

This first post will explore the different types of microphones you'll need.

Types of Microphones

The first stop in the signal flow chain is the Sound Source - an instrument (either acoustic or electric) or a vocal. You've got your voice already on your person, and It would be beyond the scope of this post to recommend all of the instruments you might want (although, if you just have one instrument - this keyboard is a pretty good choice)...We'll just start with capturing that sound source.

There are three different types of microphone: Dynamic, Condenser, and Ribbon. Each has its own special powers and works its magic in different situations. The difference between them has a lot to do with physics. I'll do my best to simplify it.

Dynamic Microphones

Let's start with dynamic microphones - the workhorses of the recording world. Dynamic mics work by using a diaphragm (a thin piece of material) attached to a coil of wire that moves inside a magnetic field. When sound waves hit the diaphragm, it moves, and that motion generates an electrical signal. They're great for handling high sound pressure levels, making them perfect for loud instruments like drums and guitar amps. Also, pretty much everything in a live setting.

The Shure SM57 and the Shure SM58 are the industry standard for dynamic mics. Cheap, durable, every recording studio has a collection of them. If you only have one microphone, it should be one of these two.

Condenser Microphones

Condenser microphones are a bit more delicate. They use two charged plates to capture sound. When sound waves hit one of the plates, it causes the distance between the plates to change, and that creates an electrical signal. They are usually split into two categories: Small-diaphragm, and large-diaphragm...I'll let you figure out the difference. They are very good at capturing every nuance of your performance. They're fantastic for vocals, acoustic instruments, and capturing the subtleties of a delicate piano or acoustic guitar.

A great budget condenser microphone is the Blue Spark (update: The Spark has been replaced by the Blackout Spark). It's a great all around condenser with a nice warm tone, but particularly good at vocals (whether spoken or sung). It's also great at handling acoustic instruments - guitar, violin, cello, etc.

Ribbon Microphones

Finally, we have ribbon microphones. They work by using a thin ribbon of metal in a magnetic field. When sound waves hit the ribbon, it moves, generating an electrical signal. Ribbons are known for their warm and smooth sound, making them great for recording strings, brass instruments, and even vintage-style vocals.

Ribbon microphones tend to run a little more expensive on average than dynamic or condenser. But, a decent choice here without breaking the bank is the MXL R144. It's dark and smooth, and it has a nice natural sound.

All of these microphones are around $100 for just the microphone. However, you'll also want some other stuff that will make your microphones work.

Stands

It holds your mic in place - so get a sturdy one. I prefer boom stands because they can be adjusted a lot more. The stock boom stand on Amazon does fine.

Cables

Most microphones use XLR cables to their source, however newer mics (especially for podcasting) use a USB connection. You'll probably want a few of these each in a different length. If you just choose 1, probably go with a ten footer.

We didn't really talk about it because they don't need a microphone, but instruments with a pickup (such as an electric guitar) use 1/4" cables rather than XLR. (As an aside about recording this, I'd run a 1/4" from an electric guitar to its amp, and then stick a SM57 in front of the amp to record it)

Pop-screen

This takes care of really harsh 'P' and 'S' sounds when you're recording vocals of any sort. Here's a pretty good one.

Shockmount

For Condenser and Ribbon Microphones. This keeps ground vibrations from your room from interfering with your recording. These are typically specifically engineered for the microphones they go with - so you will often get one with your microphone purchase. If it doesn't come with it, and you need to purchase a generic one, you'll want to research and see if it is compatible with your mic.

Hopefully this has been a helpful crash course into the world of microphones. Next time we will look at the next stop in the signal flow chain - how to get from your microphone to your computer.

Scaling the Wall: A Composer's Guide to Overcoming Writer's Block

Check out my new eBook!

Even though there’s probably not any hard research on it, I feel pretty confident stating that exactly 100% of composer’s throughout the course of history have experienced Writer’s Block. Put it right there on the list of inevitables with death and taxes.

I know this is a topic on a lot of composer’s minds. Almost every single masterclass or lecture I’ve given to a group of composers, one of the questions at the end is always about dealing with writer’s block. It’s perhaps the question I get asked most often.

I have certainly dealt with it more times than I would like - I feel like my ADHD might impact the frequency. And somehow, each and every time it feels like reinventing the wheel to get out of it. So, for the last few years, I’ve been meticulously documenting exactly what has happened when I fell into writer’s block, what I did to get out of it, and what I did to maintain creativity.

And today, I’m excited to announce that I have compiled all of those strategies into a step-by-step guide, and I’ve put that guide into an eBook for all composer’s to use the next time they inevitably fall into writer’s block.

We’ll look at 1) how to get out of writer’s block, 2) the importance of mental health and creating a healthy relationship with your work, and 3) strategies for maintaining creativity.

All of the things in this eBook are strategies that I personally use in my daily life as a composer, and I think you will find this guide immensely helpful.

So if you are stuck in the pit of writer’s block, desperately looking for a ladder to scale the wall, check out this guide.

Making Rejection Your Ally

For musician of any sort, rejection is a common occurrence…and I’ll be honest, that sucks. Whether it's a rejection letter from a publisher or record label, a negative review from a critic, or not getting the gig you wanted, rejection can be a tough pill to swallow. But rejection doesn't have to be 100% bad. In fact, if you approach it with the right mindset, rejection can be a powerful ally to help you grow as a musician. So, today I want to give some tips I’ve learned on how to deal with rejection and use it to your advantage.

1. Don’t take it personally

First off, remember that it's not personal. I know that’s easier said than done. When you're rejected, it doesn't mean that you're a bad musician or that your music isn't good enough. It simply means that the person or organization that rejected you didn't see a fit for you at this particular time. I understand that doesn’t make it any easier. But. Remember that the music industry is subjective, and what one person likes, another person may not. So don't take rejection as a reflection of your talent or worth as a musician.

This is a rather difficult thing to do. What is more vulnerable than putting your art out into the world? More often than not, It’s not just something you made, but rather it’s a piece of you.

Let’s look at some of the more frequent causes of rejection:

Composition Competitions

Wow, do I have a lot of thoughts on composition competitions. Most of them are not relevant to this discussion so I’ll try to sort through what is pertinent. Each organization who puts together a competition like this probably has a particular sound in mind for the piece they’d like. If not, then you’re looking at dealing with the particular preference of the judges. Neither of these are a reflection on you as a composer.

I love watching cooking competitions. During the judging you’ll hear discrepancies like one judge saying “my meat is overcooked” or “it’s got too much salt for my liking”, and then the next judge will completely disagree with them and say that the dish was executed perfectly. In those moments, it’s hard not to think about composition competitions and the judging that goes on behind the scenes that the composers don’t know about. I have no idea what those judges are looking for - music is a subjective art, not an objective sport. Maybe that judge just wanted a little more chromaticism, a little less polyphony, or any number of other things.

Many of these competitions even require you to take your name off before you submit, so it’s really not personal in those cases. It still feels that way sometimes.

Labels and Publishers

I feel like it’s probably difficult to overstate how many submissions labels and publishers get from musicians on a daily basis.

I once sent in a choir piece to a music publisher that I was rather proud of. The choir who commissioned it had done a spectacular job with the premiere. I was encouraged by the director of that choir to send it to a particular publisher that they had a connection to. After months of waiting, I finally got a response: “This is a beautiful piece! I love it! Unfortunately, we are going to have to pass because we don’t think it will sell all that well.”

Sometimes it’s very obvious that you aren’t the correct fit with a label or a publisher. I’m probably not getting too many record deals by sending my demo off to a heavy metal label - and that doesn’t cause me any pain. It’s when it seems like you would be a good fit, and the executives disagree that this gets hard.

University Music Programs

I’m not even going to pretend that I have even a 1% understanding of the university admissions process. But it’s definitely a common source of rejection among musicians.

Concluding this section: Some composers specifically try to get rejected a certain number of times per year. This does a few things: 1) it’s proof you’re putting yourself out there, 2) gives you a better chance of being accepted for something, and 3) firmly accepts rejection as an unavoidable reality, and in so doing that takes away some of its sting.

2. Look for constructive criticism

Okay, it’s one thing to not take it personally, and just shrug it off, but how can we use that rejection to move forward? One of the worst parts of most rejections letters is that there is absolutely no comment about why you were rejected. It feels like you sent your music to a magic 8 ball and it just responded “you lose, try again.” But. There are those times where we do receive comments that go along with the rejection; and that’s when we really need to take an honest look at what suggestions have been offered. I will be honest and say that I spent a lot of the first decade of my career dismissing suggestions I was given because they just ‘didn’t understand’ the piece. Yeah, that was dumb.

Look for any constructive criticism that can help you improve. This may come in the form of feedback from a record label or producer, or it may be in the form of a negative review that points out specific areas that need improvement - or even from a performer who played your piece. While it can be tough to hear criticism about your music, try to take it as an opportunity to learn and grow. Look for the nuggets of truth in the criticism and use them to make your music better.

What to keep, and what not to

This is a really tough question to answer. I would say there are kind of three categories of responses to criticism?

What you immediately should dismiss.

Is it constructive? If not, get rid of it. If you implemented that suggestion, would it go against who you are as a composer? If so, dismiss it. Like I said earlier, deciding what to dismiss can be a hard rope to balance on (mostly from youthful arrogance), but over time I think it becomes easier to recognize what you should immediately dismiss.What you should implement right away.

If your comments said something like “violins can’t play this passage,” or, “This notation is unreadable”, or “You forgot to transpose your horn part” (all comments I’ve gotten) - fix those things immediately. These have less to do with your musicality, and are more technical in nature. Always take those as a learning opportunity, and try your hardest to not make those mistakes twice.What you should file away for later.

I think the majority of feedback we get on our music falls in this category. Maybe we didn’t fully understand the suggestion at the time, but after some thought, it was correct. Or, maybe it was a suggestion that you a little uncomfortable hearing, but then thought “what if I did experiment with trying that?” I think a lot more of the comments we receive are applicable to us than we may think at first.

3. What can you do better?

The unpleasant truth is that rejection can be a valuable learning experience. Take some time to reflect on what went wrong and how you can improve for next time. Did you not prepare enough for the audition or interview? Did you not have the right materials or press kit? Did you not research the organization or individual enough before approaching them? If you know of the specific reason for the rejection, use it as a learning opportunity to make sure you're better prepared next time. Of course, sometimes you do everything right and it still doesn’t work out…so for that, refer back to section 1.

An opportunity for Improvement

As artists, our relentless pursuit should be in getting better at our art. Rejection and criticism offers us that very chance. And it gives us a perspective that is very different than our own. Blind spots are notoriously hard to see.

What if your favorite part of the song is the very thing that is making the song not work? You’ve got to be willing to part with it. Cut your best material if it isn’t right for the piece (but don’t throw it away, find some other, better suited spot for it).

Teachability

A lot of it comes down to how teachable you are willing to be. It’s like a parent who insists their child can’t be the problem because their child is perfect. You’re going to miss a lot of opportunities for improvement based on how willing you are to change what needs to be changed, and to learn what needs to be learned.

Practice.

Every musician hears this every single minute of our lives, so I won’t linger here too long. But, yeah. Practice your craft. And I’ll turn the mirror back at me and tell me to practice my craft too.

4. Stay positive

It's easy to get discouraged after being rejected, but it's important to stay positive. Remember that rejection is a part of the music industry, and every successful musician has faced rejection at some point. Use rejection as motivation to work harder and improve your music. Focus on the positive feedback you've received and the progress you've made so far. Remember why you started making music in the first place, and let that passion drive you forward.

The value of your music

Here’s the truth: your music has intrinsic value by the very fact that you saw enough value in it to make it in the first place. And there is an audience for it. I also know how difficult it is - even with how connected we are through the internet - to find that audience. Someone is out there, who upon finding your music will say “wow, I wish I had known about this sooner.”

5. Keep moving forward

Finally, don't let rejection stop you from pursuing your dreams. Keep moving forward and continue to make music. Remember that success in the music industry often comes after many rejections and setbacks. Keep honing your craft and seeking out new opportunities. The more you put yourself out there, the more chances you have of finding success.

Start on the next one.

There’s a great scene in “Tick, Tick Boom” where Jonathan Larson (played by Andrew Garfield) has just had a successful musical workshop, but didn’t receive any offers for his musical to be produced. He asks his agent “what should I do now?” or something to that effect, and she simply responds: “Get to work on the next one.”

Conclusion

Remember first and foremost that rejection is subjective. What one person may reject, another person may embrace. Keep that in mind as you continue to pursue your music career. Don't let rejection define you or your music. Keep creating, keep learning, and keep pushing forward. Eventually, I believe your hard work and perseverance will pay off.

Use rejection as an opportunity to learn and grow, and don't take it personally. Look for constructive criticism, learn from the experience, stay positive, and keep moving forward. With these tips, you can turn rejection into an ally to help you achieve your musical goals.

Starting a New Piece

I thought maybe I would share 3 strategies that helped me overcome writer’s block, and actually start this project.

I’m starting a brand new piece today. I’ve had this idea for a while, but it’s just been sitting in my notebook.

So, I thought maybe I would share 3 strategies that helped me overcome writer’s block, and actually start this project. I’ll be coming at this from a composer’s perspective, but I imagine these strategies probably would transfer to just about any creative endeavor.

1. Start with what you have

What’s in your sketchbook

That stuff you doodle on a napkin

Voice memos you made on your phone

Is there anything you’ve already thought of that can be the basis for your new project?

Are there multiple fragments in your sketchbook that could be combined for this project?

For this piece, I’m starting with a melodic fragment that I found in my notebook (and the concept of “home”, but more on starting with concepts in a little bit). Those little fragments can be expanded to create an entire piece. It does need to be the right fit though, so it’s helpful to have a notebook full of possibilities.

So, If you haven’t already, start a sketchbook/ideas notebook/Voice Memo Catalog. This can be great for starting projects, but it can be especially helpful for all of those times you’re working on something else, but you’ve got a really good but totally unrelated idea.

2. Start with a Story, an Emotion, or a Picture

Sometimes the story comes to me before any music does.

Pick an emotion, any emotion will do. Then brainstorm every single way to evoke that emotion in musical terms. I also like to ask what is the opposite of that emotion, which can give the piece a nice contrast.

Start with a picture in your head: How would you create that scene in music? How would this look in another artform? For example, how would my music look if it was a painting? What would this piece be as a film?

I’ve been pondering different ideas of “home” for a while, and I think that will be the basis for this piece. Perhaps each idea of home can be the basis for each movement, we’ll see. But, having that concept in mind allows me to then think about how to translate that to music.

3. Set a limitation

With literally every possibility sitting before you, it can be extremely intimidating to actually start down a path. All art requires a limitation, or it would never get made. If I just choose the instruments I’ll use, and the length of the piece, I’ve excluded a lot right there, right off the bat. This is really helpful, because you now no longer have to worry about the millions of possibilities you won’t pursue in this project.

I’m starting with cello, and piano, and I want it to be about 10 minutes long.

Take away something. What if you tried to write with no melody? I find this very helpful especially if you tend to do something all the time. I tend to focus too much on melody, so taking it away can really help you focus on other things and come up with something different. You can discover a lot of cool ideas when you are forced to do something different than usual. If you always write in G major with 4/4 time, force yourself to write in anything other than G major 4/4.

Start with a limiting concept. Like a piece built entirely on 3rds. Or, a unique scale to work with. Or, never use C#.

Hopefully, that gave you some piece motivation or inspiration for starting your next project. I should probably stop procrastinating and get back to writing.

Should You Update Your Old Music?

I’m entering year 12 of my composition career. And here’s the thing: a lot of the music I wrote in those first few years is not quite up to my current standards. I’ve improved a lot - which is definitely what you want. A lot of that early music got one or maybe two performances and they’ve kinda just been collecting dust ever since. Or, maybe it’s a song on an early album that receives exactly 2 streams per year.

I was recently asked if I have any works for a particular choir voicing - and I did…but it’s one of those old pieces. I’m not exactly sure I want to hand that piece to an ensemble. We probably all have those moments where we look back on our past work and think: “what was I thinking? Violins don’t even have that note”, “these lyrics sound like they were written by a 3rd grader, and what’s with this guitar part?”, “I don’t even remember writing that”, or, “I’m confident the sopranos hate me for that - and they have every right to”.

That sent me down a rather deep rabbit hole: should I update my old music? Both from a practical and philosophical perspective. Should composers, in general, go back and fix the mistakes of their earlier works? If so, what exactly should they fix? Minor errors? Complete overhauls? All the above?

Today I want to look at the pros and cons of updating your old works, and I’ll let you know what I concluded about updating my own old works.

First let’s look at a few benefits of revisiting and revising your old music:

1. Make an unplayable piece performable.

Pieces that I wrote back in the day on the free version of Finale lacked any sort of regard for whether real life musicians could play that part. If a piece actually made it into the performer’s hands, they would usually tell me if a passage was awkward - or impossible. But that doesn’t mean that we always end up with a smooth, idiomatic part for all of our players, there’s a difference between “playable” and “comfortable”. Once I had a horn passage that was technically in the correct range, but it was the highest part of the range, and it stayed there for quite some time, and I forgot to include any places for the player to breathe. I think the guy’s lips fell off during one rehearsal.

If you’ve got a piece that you like but it has some problems like this, revising it could give the piece new life, or at least a longer life. This is especially important for composers that are self-published as you are your own editor 99% of the time - all mistakes in the score are your fault. And honestly, errors are like whack-a-mole - you take care of one of them and five more pop up in its place.

2. You didn’t have the resources at the time

Maybe you didn’t have the best quality microphone when you recorded it the first time. Maybe your voice has improved. Maybe you’ve gotten better at guitar and so you could record that solo the way you heard it in your head. Maybe you wanted a string quartet, but all you could find was a violin, a clarinet, and a tuba - so you went with that.

Revisiting an old piece can improve the quality of the piece if there are more resources available to you now. If you’ve been dissatisfied with the way a recording or a piece turned out the first time, and you feel like your artistic vision wasn’t fulfilled, this might be a good option.

3. Your artistic vision changed.

Now, this one is perhaps controversial from a philosophical point of view. But if you’re okay with doing a complete overhaul of your work, you might revisit a song because your vision has changed. Maybe you really like the original idea you had, but the execution of it back then is nothing like how you’d do it now. As you grow and evolve as an artist, your creative vision will change, and you can bring your old music in line with your current direction.

On a similar note, I’ve often been curious what it might sound like if some of my favorite artists took their earliest hits and did a “if I wrote this now” version. What if Toto wrote “Africa” today? What would that sound like? Some music (stylistically) is really the product of the time it was written and might not translate well to current styles, but it might be something worth trying with your old stuff.

Drawbacks to updating your old music:

1. It takes time away from new music

With all of these benefits listed above, you do have to consider the price: revising your old music takes time. And if you’re like me, you already find that 24 hours simply is not a long enough day. You’ve got to analyze whether the benefit of revising an old piece outweighs the cost of not working on a new piece.

2. For some, Philosophically, this is like “rewriting history”

For a number of composers, they feel like their entire life’s work should effectively serve as their musical auto-biography. In that sense, it would be like “rewriting” your personal history if you change past works, especially if it was just to bring it in line with your current vision.

And yeah, I kinda see that - if there is a lyric, or a musical moment that came out of a very specific moment in your life - it would change the meaning if you revised the piece.

3. Your fans might not like it.

Certain old music has a particular charm. Many people miss the noise that comes from old vinyls on the new digital music. If you’ve got a piece or a song that is well-loved, it might not be received well if you change it. Not that everything you do has to be to make the fans happy, it’s just something to consider.

Furthermore, you may not like it. You might spend all of this time revising, only to find out you like what you did in the first place better. Sometimes it is hard to capture that magic a second time. But also, it might not be fixable. There’s a profound frustration that festers from trying to resuscitate a piece that is already six feet underground.

So, how much should you revise?

This takes into consideration all of the pros and cons we just talked about. If you go with a “fix the errors” approach, that won’t take nearly as much time as a complete overhaul. I’d also argue that fixing minor errors doesn’t change your past artistic vision.

And if you do decide to revise a piece now, is there a point in the future that you’d want to update it again? Maybe that would be a waste of time…or, maybe it would be a cool series throughout your life to just update the same piece every 10 years or something like that.

Ultimately, it’s up to you. You know your own artistic vision and goals. So, what am I going to do? I’m going to fix enough errors so that all of my previous works are playable, and enjoyable. But, I’ll leave major structural changes in the past. Did I write a low F for a violin? I’ll fix it. Did I incorrectly place syllabic stress in a few places? Those are getting left alone.

I like the work that I’ve done, and I’d like for those pieces to continue. But I also stand by what I wrote back then, even if it isn’t up to my current standards, or what I would have done if I wrote it today.

So, what do you think about revisiting and revising your old music? Let me know in the comments!

Keys and modes

Here’s a three part video series looking at key signatures, why we need them, how to recognize them, and then how to name the keys and the modes based on their signatures.

Here’s a three part video series looking at key signatures, why we need them, how to recognize them, and then how to name the keys and the modes based on their signatures. I recommend watching these three videos in order.

The charts used in these videos is available in the resources section below.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

How Ligeti Orchestrates A Motif

Orchestration can seem daunting. There can be too many possibilities, and there are a lot of instruments to keep up with. Today we're studying Ligeti's Ricercata III - looking at how he took a piece for solo piano, and orchestrated it for woodwind quintet (flute, oboe, clarinet, horn, and bassoon).

Orchestration can seem daunting. There can be too many possibilities, and there are a lot of instruments to keep up with. Today we're studying Ligeti's Ricercata III - looking at how he took a piece for solo piano, and orchestrated it for woodwind quintet (flute, oboe, clarinet, horn, and bassoon).

Then in the second video, I'm taking my first ever piece for solo piano, and orchestrating it for woodwind quintet. I’ll be walking you through basic principles of orchestration based on the three ideas we talked about in the Ligeti orchestration.

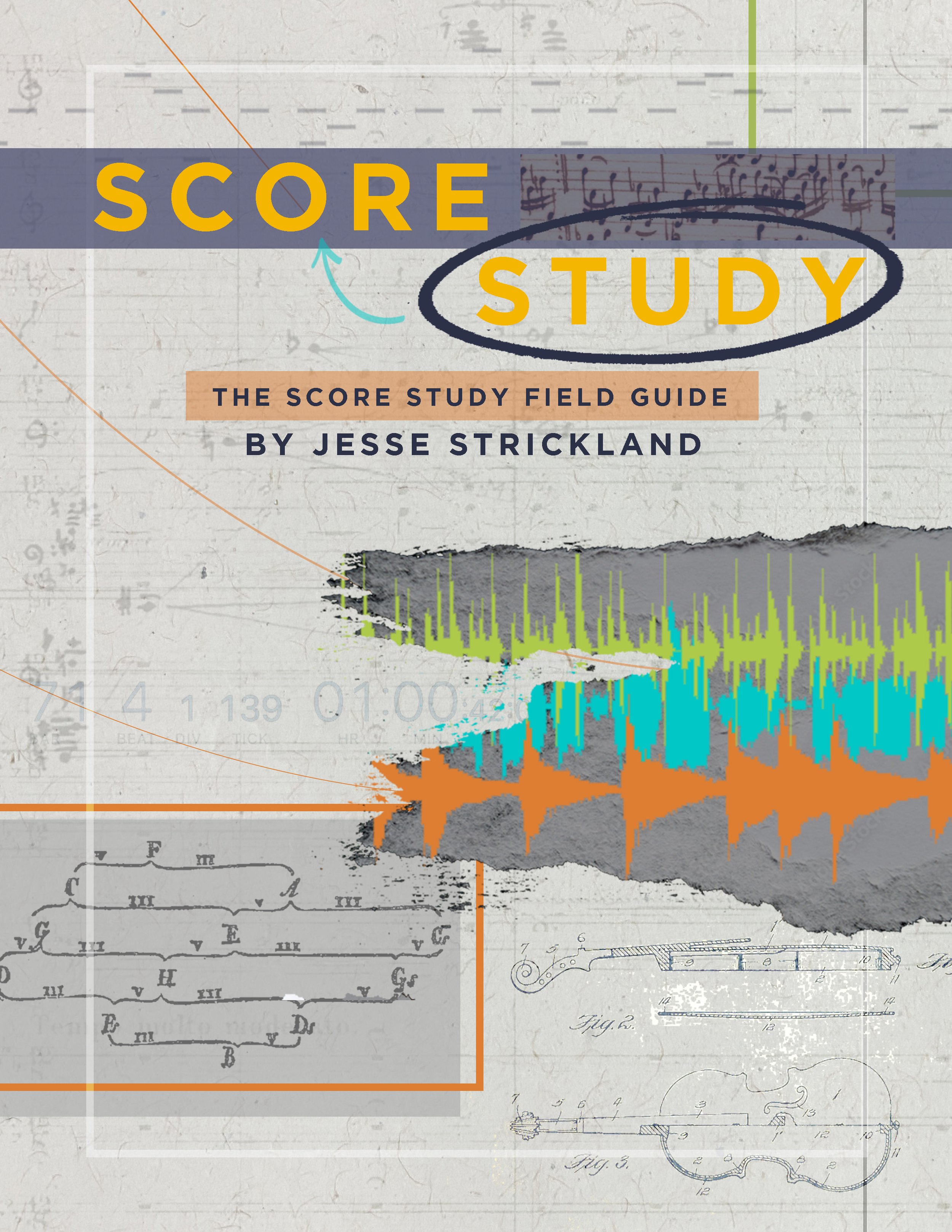

Make sure to get your copy of the Score Study Field Guide in the resources section below.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

Sonata Form in Two Minutes (roughly)

Volumes of Dissertations have been written on the topic; and while it is endlessly nuanced, it doesn't have to be hard to understand the basics. Today, we're looking at the exposition, development, and recapitulation of Sonata-Allegro Form.

Volumes of Dissertations have been written on the topic; and while it is endlessly nuanced, it doesn't have to be hard to understand the basics. Today, we're looking at the exposition, development, and recapitulation of Sonata-Allegro Form.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

What Do Chord Inversion Numerals Mean?

It's Two Minute Music Theory's 7th Birthday! I thought it would be appropriate to release a good old fashioned TMMT episode that's not 2 minutes long. Thanks to everyone for all of your support the last 7 years. Here's to the next 7.

It's Two Minute Music Theory's 7th Birthday! I thought it would be appropriate to release a good old fashioned TMMT episode that's not 2 minutes long. Thanks to everyone for all of your support the last 7 years. Here's to the next 7.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

Five Tips For Understanding Music Theory

Music Theory has built a reputation for being a very confusing subject. Some jokes around the internet even suggest that it is harder than rocket science. But it doesn’t have to be that way. There are things that we can do to help make music theory make more sense. And I’ve got five of them for you today.

Music Theory has built a reputation for being a very confusing subject. Some jokes around the internet even suggest that it is harder than rocket science. But it doesn’t have to be that way. There are things that we can do to help make music theory make more sense. And I’ve got five of them for you today.

More information about the online course UNDERSTANDING MUSIC THEORY can be found below.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

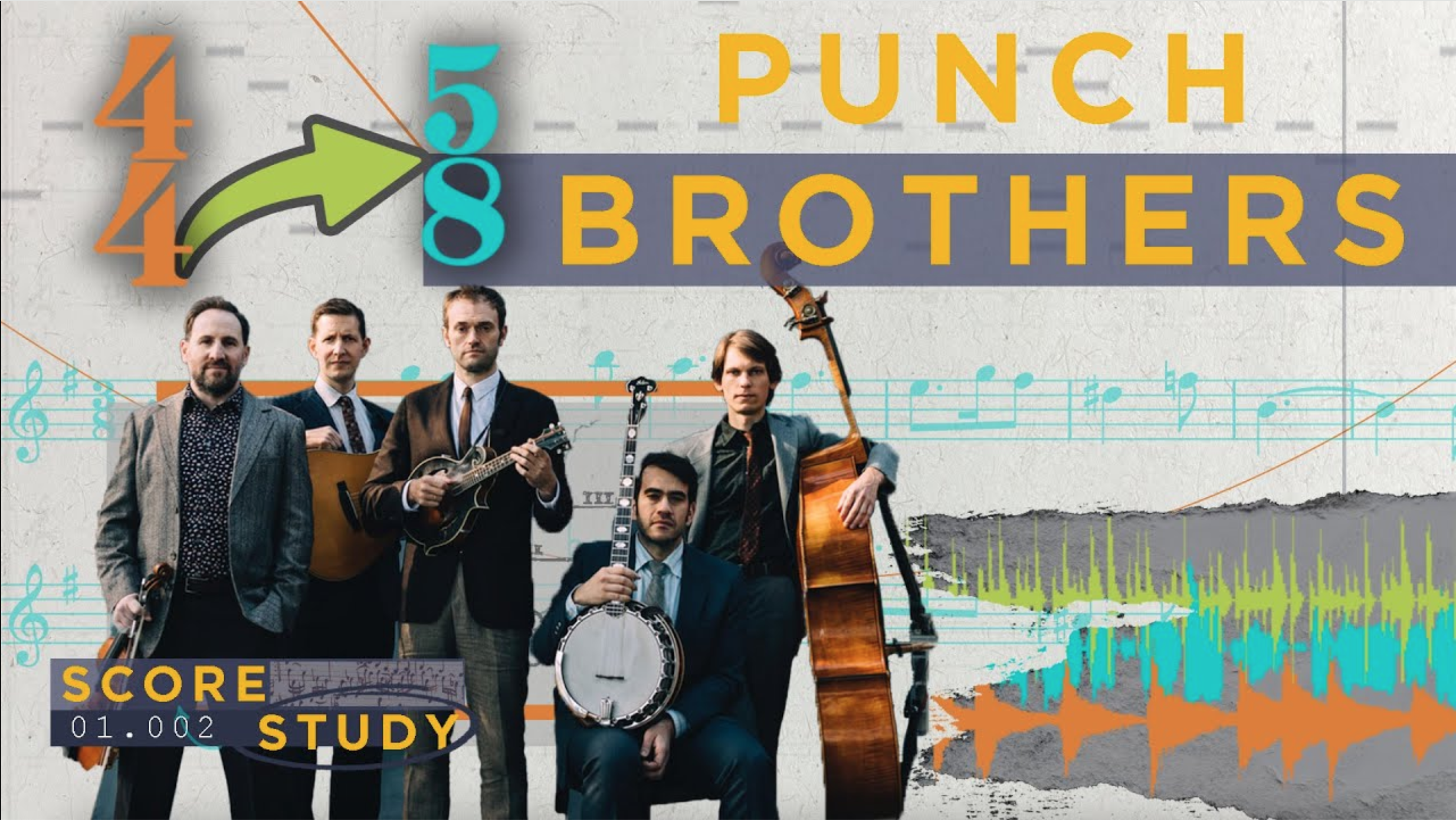

How the Punch Brothers Converted Church Street Blues from 4/4 to 5/8

Today we're looking at 6 tips for converting from common meter to complex meter by analyzing the Punch Brothers cover of Tony Rice's Church Street Blues.

Today we're looking at 6 tips for converting from common meter to complex meter by analyzing the Punch Brothers cover of Tony Rice's Church Street Blues.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

Re-Writing My First Melody Using Music Theory

I get a lot of questions about how to use music theory to write music. So, today I'm taking a look at a melody I wrote a long time ago to see how I can improve it using concept we learn in Theory I and II.

I get a lot of questions about how to use music theory to write music. So, today I'm taking a look at a melody I wrote a long time ago to see how I can improve it using concept we learn in Theory I and II.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

Postcards

I’ve started a new instrumental composition series. Each piece in the series is written based on a photo that I took somewhere on this planet.

I’ve started a new instrumental composition series. Each piece in the series is written based on a photo that I took somewhere on this planet. In addition to the photos being a good creative prompt, each of them are meaningful memories to me. I’m planning for the first collection to have 10 Postcards.

I’ve got the first two here for you.

The first I took on the Little Platte River in Nebraska at our campground. As far as the music goes, the story is Sunset on the Little Platte River in Nebraska. Sleep is calling, but an active mind initially resists, but eventually succumbs.

The second is from the Upper West Side in New York City. It's called the city that never sleeps, so perhaps aptly, I took this photo at 2am the night from the roof of my building. Fun Fact, the photo was taken in late January, and you can still clearly see a Christmas Tree in one of the window on the right.

Score Study: The Magic Hidden in the Harry Potter Theme

Starting a new series today! This is the first episode of a new series called Score Study, where I’ll be looking at very specific moments in a piece of music, breaking it down from a composer’s perspective, and then we’ll try to write something as an exercise from what we’ve learned.

Starting a new series today! This is the first episode of a new series called Score Study, where I’ll be looking at very specific moments in a piece of music, breaking it down from a composer’s perspective, and then we’ll try to write something as an exercise from what we’ve learned.

Make sure to get your copy of the Score Study Field Guide below!

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

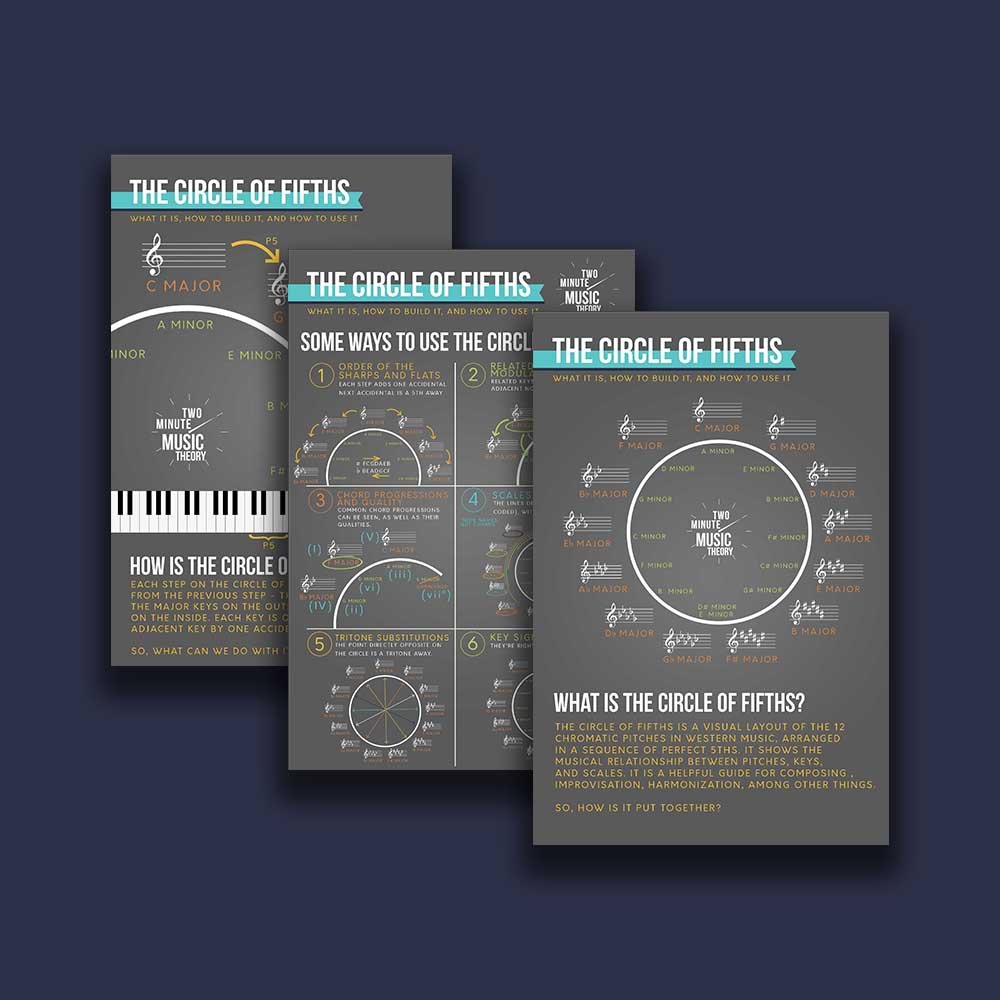

What Is The Circle of Fifths And How To Use IT

It’s one of the most useful tools in music theory, but what is it and how do we use it?

Make sure to get the chart from this episode down below!

It’s one of the most useful tools in music theory, but what is it and how do we use it?

Make sure to get the chart from this episode down below!

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.