The Simple Way All Scales Work

It may seem like a lot to learn every scale, but there is a simple pattern to the way that all scales work.

Make sure to join the Double Bar Newsletter. A weekly email newsletter designed to help musicians create better music and find their signature voice through deepening their understanding of music.

Why You Should Learn EVERY Scale

Today we are starting a four part video series on the theory of musical scales. In this video, we are talking about the practical reasons why a musician would want to learn every single scale.

Make sure to join the Double Bar Newsletter. A weekly email newsletter designed to help musicians create better music and find their signature voice through deepening their understanding of music.

The Inconsistency of The Beatles’ Album Titles

So. I'm doing some music history research, and for this particular project I'm having to look at the Billboard charts each week in the 1960s. That’s when I noticed something: there in the Top 200 is an album called “The Beatles’ Second Album.” I’ve never heard of this before, and so I started digging.

Turns out, the Beatles albums have different names in the UK than they did for their original US releases. For example, the Beatles had an album titled "With the Beatles" released in the UK on November 22, 1963 (I wonder if anything else happened that day?) which included 14 songs and a runtime of 33 minutes, but when it released in the US in January of 1964, it was titled "Meet The Beatles" and only included 12 tracks and a runtime of just over 26 minutes.

The reason seems to be that Capitol Records was trying to maximize profit for American audiences, go figure. This strategy included releasing more albums with less songs. As I was pulling on that string, I found out that 7 albums released in the UK before Sgt. Peppers, but that translated to 11 US albums.

It seems that at the time UK audiences were more accustomed to 14 song albums, while US record companies typically only went with 10-12.

In some cases (as was the case with “With the Beatles” and “Meet the Beatles”), there’s a pretty direct correlation between a Beatles UK release and its US counterpart. (Note how the US release bills this as “the first album” - despite it being the 2nd album from the Beatles (and in fact, the second released in the US…but that’s another story)

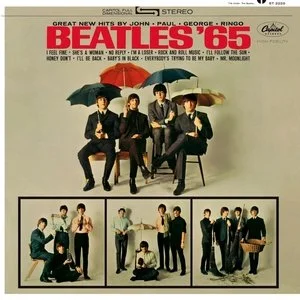

The same could roughly be said of “Beatles for Sale” which released in the UK in 1965, and it’s US counterpart “Beatles ‘65”

However, not all of the US releases were direct counterparts to UK releases. As was the case with the confusingly titled “The Beatles Second Album” (which was the third released in the US…but only the second released by Capitol Records). This release was a compilation of a number of Beatles tracks and doesn’t directly correlate to any UK album.

There’s not really a major point that I’m trying to make here - mostly an observation. And while I can’t say much about the research project I’m working on, I assure you - this is 1000% unrelated. A complete side quest. It is literally something I just happened to notice while looking over the Billboard charts from 1964.

You want to know what else I noticed in the 1964 Billboard charts? Alvin and the Chipmunks sing the Beatles is a thing. It’s a very real thing that actually happened. It was in the US top 200 for three weeks in 1964. Maybe this is common knowledge and I’m completely late to the party, but wow, I did not see this coming. You can listen to that glorious work of art here.

Let’s land this plane before I get any further off whatever point I was trying to make. I hope you have enjoyed this particular oddity of music history I happened upon.

How Many Musical Elements Are There?

It seems like a question we’d know the answer to. We all kind of know what the elements of music are…right? Today, I’m going on a journey to figure out exactly how many there are. And more importantly, we are talking about why this is a worthwhile endeavor.

If you’re the kind of person who wants to deepen your understanding of music - I highly recommend my email newsletter. I’m sending out a bunch of resources in composition, music theory, and musicology to help you become a better musician.

ARTURIA MINILAB 3 - A 6-month review

I have had my Arturia Minilab 3 keyboard for about 6 months now, so I thought I'd give it a proper review. It's a nifty little gadget that has managed to wedge itself neatly into my cluttered workspace (and my heart). Was that too much? That was too much, wasn't it?

First Impressions: Design and Build Quality

At first glance, the Minilab 3 looks like it was designed by someone who’s had their share of cluttered desks. It's not any wider than my Macbook, so it fits wherever my laptop does. That was one of the bigger selling points for me. I take it with me on airplanes. The TSA will give you some puzzled looks, but I know they are just jealous. I also like the sturdiness of the design. Some of the other portable controllers I have tried feel like they might snap in half if you look at them wrong. It’s got a bit of heft, which is reassuring when you’re furiously tapping out a drum beat or tweaking a filter.

Playability

Now, let’s talk keys. The Minilab 3 has 25 of them - ranging from C to C two octaves higher. They are slim, unweighted, and velocity-sensitive...perhaps too sensitive at times. It can be difficult to play something in the middle velocities. But you know, maybe I'm just bad at playing them? The slim nature of the keys takes some getting used to if you are only used to the size of a regular piano.

Speaking of buttons, the 8 RGB backlit pads are a joy...particularly to my 2-year-old. They’re responsive and perfect for all sorts of musical shenanigans, from drum programming to sample triggering - I don't use it much, but I understand this keyboard works really well with Ableton. I'll be honest, I didn't think I would use the drum pads, but I've found a lot more use for them than I expected.

What I haven't used is the knobs and faders - of which there are 8 and 4, respectively. I may find uses for them eventually, but my goal wasn't really to use every feature of this keyboard - I just needed to replace my old full-sized midi controller with something smaller, and more affordable.

Inputs and Outputs

I will say, the USB port is nice. But, I only have two of them on my computer, so that can be a bit of a problem sometimes since I also use the Focusrite Scarlett, which is also a USB. I don't know what I'm saying here as a solution? Maybe Apple just needs more USB ports in their Macbooks.

Software Integration

It comes bundled with a bunch of softwares (including Ableton Light)...and I haven't used any of them. I was mostly interested in its compatibility with the softwares I already use in my workflow: namely Dorico and Logic. In that department it does exactly what I need it to do. I can hook up the Minilab, load in my library of choice, and off we go.

Conclusion

Overall, the Minilab 3 has proven itself to be a trusty sidekick. It has made my workstation more efficient, and I can take it on the road. It has an older brother - an 88 weighted-key version that I will definitely be on the lookout for when I am in the market for one.

The Arturia Minilab 3 has found a permanent spot on my desk and in my creative process. It’s compact, powerful, and incredibly user-friendly. Whether you’re a seasoned pro or just starting out, this little controller packs a big punch. It's not perfect, but it fits perfectly on my desk, doesn’t overwhelm my workspace, and it offers all the features I need to bring my musical ideas to life. If you’re looking for a MIDI controller that’s both versatile and space-saving, the Minilab 3 is a fantastic choice.

(Coming Soon) A New Music Community

I'm thrilled to share some exciting news with you! I am in the process of creating a brand-new membership community and resource site centered around Composition, Music Theory, and Musicology.

As I have thought about my musical journey - I learned so much more when my professors brought me alongside them in their work, rather than just sitting and listening to a lecture. I got to see the creative process in action as they worked through real-world problems. And that’s what I want to create.

What is the Membership Community?

This upcoming membership community is designed to be a unique blend of learning, training, and community, through direct access to my creative work in composition, theory, and musicology. It’s a place where passionate musicians can deepen their knowledge, explore new ideas, and connect with a supportive community of like-minded individuals. It’s a place where we can all get better at our craft, and become better musicians, together. The community would be built on four core values: community, accessibility, innovation, and discovery.

Community:

I’d like to create a vibrant network of musicians. Composition and music research can be very isolating activities. Communities are often only found in academic settings, but we can change that. Engage in meaningful discussions, ask questions, and support each other’s growth. No one has it all figured out - we can all become better musicians together.

Accessibility:

Whether you’re a veteran musician or brand new; a student or educator; a composer, a performer, or a researcher; the music resources in this membership are designed to be accessible to everyone. Gain insights from detailed courses, access exclusive content, and learn at your own pace. I want to give everyone the chance to improve and excel, regardless of their background, musical style, or experience level.

Innovation:

One of my personal goals is pursuing innovation. That includes my creative work, but it also means pursuing innovative approaches to learning and creating music. From advanced masterclasses to unique composition techniques, we will continually explore new methods to enhance our musicality.

Discovery:

Composition, Music Theory, and Musicology are all about curiosity and discovery. There's something thrilling about discovering a new chord you love, or finding easter eggs hidden in the music you're analyzing, or in asking questions about music and finding the answer. This is your opportunity to discover new perspectives and deepen your understanding of music.

What will membership look like?

Details are still being worked out, and I would like to take this site through a Beta testing phase (more details later), but here is what I’ve got so far:

Gold Tier:

Digital Resources

PDF guides/Ebooks, Curriculum guides/Lesson plans, Research Papers, Annotated Scores

Music Downloads

Solo sheet music/perusal scores, Singles/Albums/Stock Music

Community Access

Private Discord Server, Early Access, Priority for lessons, discount, behind the scenes

Platinum Tier:

All Gold Tier benefits plus full access to Exclusive Content:

Online courses

Masterclasses

Exclusive Video Content

Extended Cuts and Commentaries

Live Streams

Office Hours

First Priority for Lessons, Bigger Discount + Discounts on Composition Services

Get Involved early

As I work towards launching this new community, I invite you to be part of its creation. Your feedback and support are invaluable in shaping a membership that truly meets your needs. Here’s how you can get involved:

Express Your Interest: Send me an email and let me know if this idea excites you and you have interest in being a member. Would you like to be a beta tester? Let me know that too.

Provide Feedback: Send me an email and share your thoughts on what you’d like to see in the community.

Support Through Crowdfunding: There is so much work to be done to make this a reality. There's a lot of content to produce, and a lot of website that needs to be designed. It's a lot. So, I'm starting a crowdfunding campaign to bring this vision to life - I am hoping to raise $5,000 to cover the cost of creating the content, and to pay for the web designing that is needed. You can get free membership for anywhere from one month to lifetime access for your donation. Note: The Crowdfunding campaign ended on September 27.

join a thriving music community

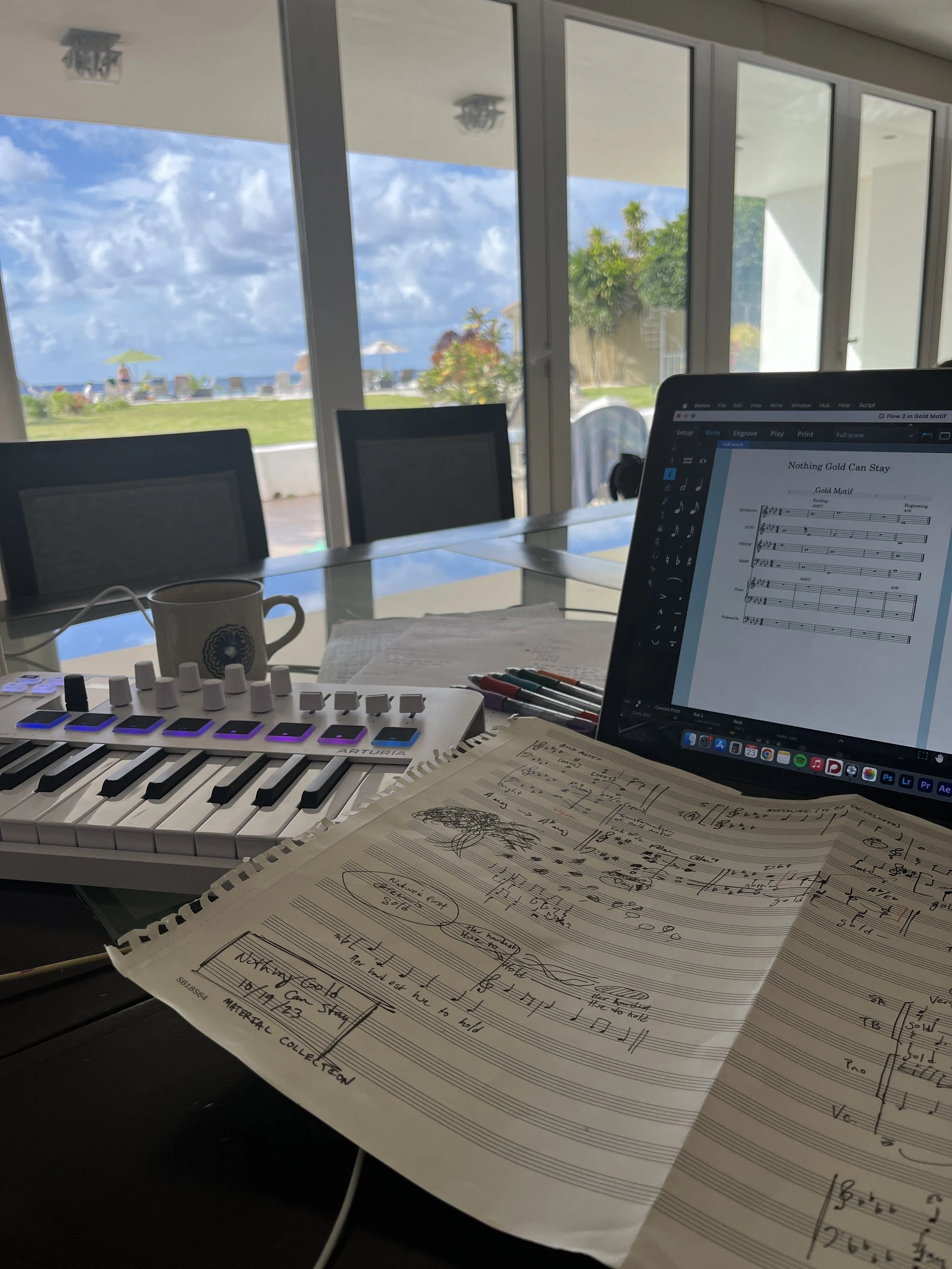

[NEW CHOIR MUSIC] Nothing Gold Can Stay

I'm extremely happy to announce this one. Autumn is my favorite season - and last autumn I was sitting there wishing the weather could feel like that year round, when I happened upon a poem, Nothing Gold Can Stay, by Robert Frost that talks about how beautiful and fleeting the patterns of nature are.

This one is for SATB + Piano + Cello - great for High School, College, or Community Choirs.

If you're putting together your Fall Program right now, 1) send me an email at jesse@jessestrickland.com and I'll send you a perusal score - along with a MIDI realization, 2) please send this to any choir directors who need this in their program.

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leaf’s a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.

What Exactly I Do As A Composer

Usually when I tell people that I am a composer, they respond with “what does that mean, exactly?”

For me, it’s a wide range activities that are all related to writing music. Here are the things that I do on a regular basis as a composer (and yes, I’d love to work with you if one of these projects fits your needs):

- Custom Pieces. These come in the form of commissions, but also they are for sale on my website. I write mostly for choirs, church choir + orchestra, and classical chamber ensembles.

- Arrangements. This is taking existing material and “arranging” it in a new way. For example, taking a classic hymn and arranging it for a church orchestra.

- Orchestration. I’ll take a song that is already written and I’ll provide all of the additional instruments for it. This is particularly important in the church world, as each church has a different make up of their orchestra.

- Editing. Taking a piece from good to great. I do this either for my own works, or for hire for other composers.

- Engraving. This is editing the notation of a digital score so that it is ready to be sent to ensembles/performers. Again, I do this for my own scores, but also other composers.

- Writing and recording my own songs. That one seems a little more self-explanatory

There are plenty of other things I do (such as teaching and content creation), but these are all of the things that I do in regards to actually writing music.

If you are a music minister, an ensemble director, or a composer who has need for one of these services, please let me know! I’d love to work with you.

4 Strategies to Finish Your Music Writing Projects

If you are frustrated by unfinished songs and pieces you’re working on: You're not alone. This is one of the most common frustrations I hear from composers, songwriters, and producers that are newer to the music writing. It’s usually one of two things:

1) You’ve written a little something, maybe 8 measures or so, and you can’t figure out where to go next, or, 2) your piece seems disjointed - it's just a random collection of ideas. Both of these will stop progress dead in its tracks.

I feel your pain. I've got a full box of unfinished music sitting in my studio. Here are four strategies that I use to finish my music projects.

1. Overcoming Perfectionism

Perfectionism is one of the biggest roadblocks to finishing music projects. It makes you constantly second-guess your work, leading to endless revisions and even creative paralysis. To combat perfectionism:

Shift Your Mindset: Aim for progress rather than perfection. Understand that no piece of music will ever be flawless, and that’s okay. (would we even like it if it was perfect?)

Set Time Limits: Give yourself a deadline to finish sections of your music. This creates a sense of urgency that can help you move past minor imperfections.

2. Zooming Out for Perspective

Another common issue is getting too caught up in the details, losing sight of the overall structure. If you find yourself obsessing over perfecting every single element without considering the bigger picture, try these steps:

30,000 Feet: Before diving into the details, create a broad outline of your piece. Decide on the overall flow and structure, and then work on the individual sections.

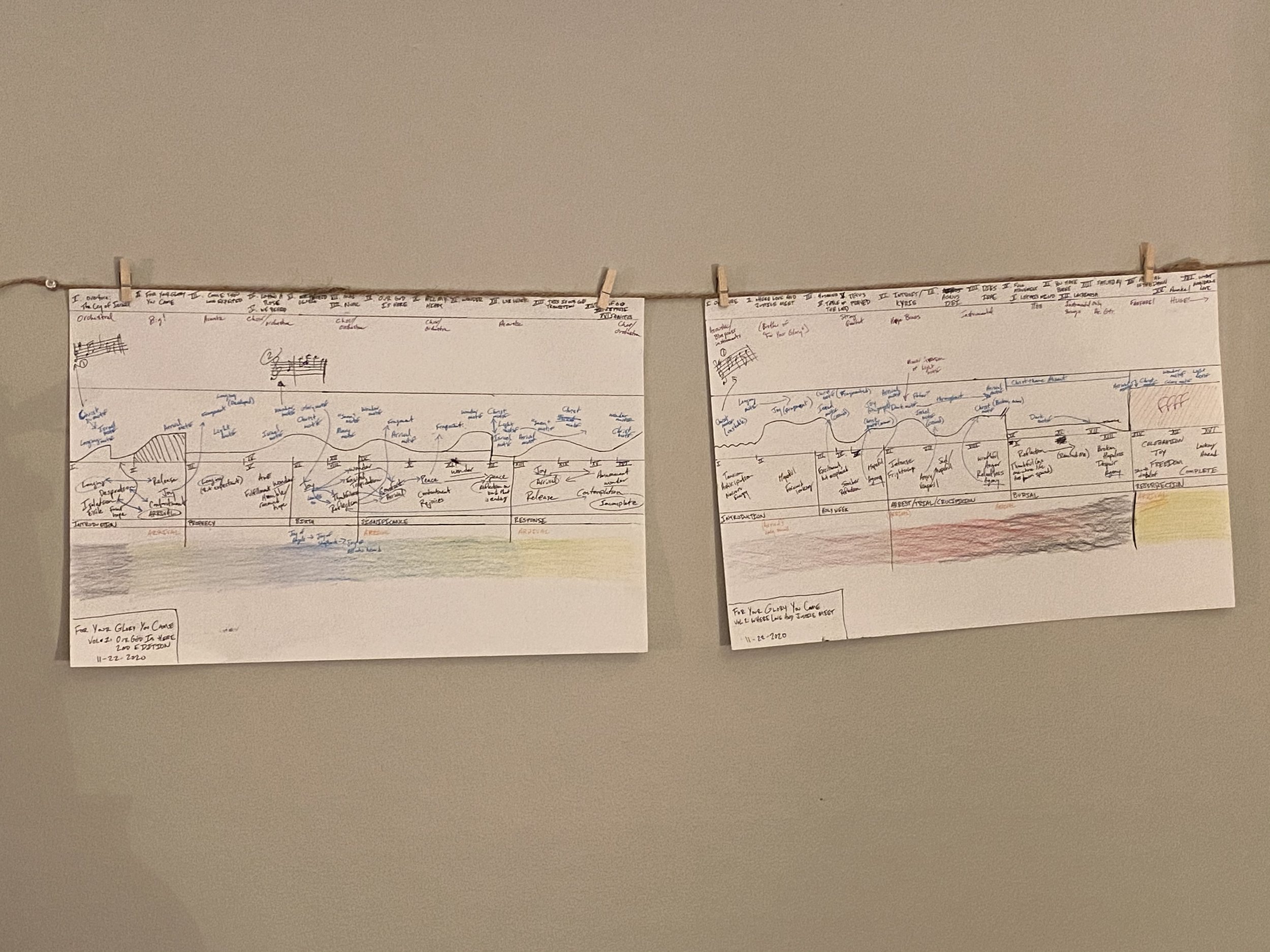

Create a “scale model”: I like to use two tools here: The Short Score, and the Timeline. Both of these allow me to put all of my ideas in physical space. Use these tools to visualize your piece from start to finish. This helps ensure all parts fit together cohesively and prevents well-polished sections from feeling out of place.

Develop and Transition: A huge mistake I see from beginners all of the time is abrupt transitions from one idea to the next. Focus on developing your main ideas and creating smooth transitions between sections to maintain a unified composition.

3. Limiting Your Material

It might seem counterintuitive, but trying to use too much material can be a major roadblock. Many composers feel the need to generate numerous ideas to fill a piece, but this often leads to disjointed music. Instead:

Focus on 1-2 Main Ideas: Most successful pieces are built around a few core themes or motifs. Concentrate on developing these ideas thoroughly.

Development Techniques: Expand, alter, reharmonize, and orchestrate your main ideas to create variety and maintain interest without introducing new material.

Creating Relationships: Ensure that your main ideas relate to each other. Use contrasts in rhythm, dynamics, or register to create a sense of unity and progression.

4. Commit to Consistent Practice

Finishing music requires a commitment to sit down and write regularly. It’s not about finding a magic cure but developing a habit and toolbox to overcome common challenges.

Consistent Practice: Set aside dedicated time for composing and stick to it. Regular practice helps build momentum and keeps you engaged with your work.

Feedback and Revision: Don’t be afraid to seek feedback and make revisions. Use criticism constructively to improve your music and move forward.

This isn’t every single obstacle, but they are the ones I’ve found to be the most common - address these, and you’ll finish more of your music writing projects.

Finish Your Music: A Free Email Course

If you're ready to dive deeper and gain more insights, I’ve written about all of these topics in greater detail in a 5 day email course. It provides practical exercises and detailed strategies to help you overcome these challenges and complete your musical works. It’s completely free, and it will only take about 10-15 minutes per day. These are strategies and exercises that I use in my own writing process - and I think you will find them useful as well.

Enroll Here: https://jesse-strickland.mykajabi.com/finish-more-music-enrollment

Four Questions for Writing Emotion in Music

Music is often emotional, and music often tells stories.

A number of years ago, I noticed that when it came to crafting emotions, and structuring my story for my music - I was usually choosing defaults.

"I'll write a happy song, and it will have 2 verses, 2 choruses, and a bridge." Nothing wrong with that. But, I hadn't intentionally decided whether or not those were the best way to express what I wanted to say.

The first thing I realized was that a good story usually has more than one emotion.

"They were happy, they stayed happy, they lived happily ever after." It's monotonously static. You need more than that for a compelling story.

So, how do we structure our stories, and convey our emotions in a musical way? Here's what I came up with: I ask myself these four questions for every song or piece I write - often before I start writing.

1) Polarity. What is the primary emotion? What is its opposite?

A lot of my music is based not just on two different emotions, but on a contrast of emotions. Emotions don't exactly have concrete opposites (like, Up and Down). Sure, maybe the opposite of Happy is Sad. But what if it is Anger? What if it is Melancholy? It all depends on the story you want to tell. Love can be the opposite of Hate, but it can also be the opposite of Indifference. Asking this question helps me understand the big picture structure of the song.

2) Gravity. Where are we being pulled? What is the force creating the pull?

You could ask this in a musical sense (as in, the leading tone is pulling us to the tonic). But you can also ask this in an emotional sense to help you figure out where your piece wants to go.

3) Journey. What is the emotional journey from start to finish?

If polarity helped me understand the structure from 30,000 feet, Journey is the specific twists and turns the piece took to get there.

There may only be two emotions in the piece - in that case, this is a roadmap of how they interact. But, often there are a lot of emotions, and only two that are primary. Then I need to ask, how do these emotions weave their way into the narrative.

4) Arrival. Where did we end up?

Some composers (and listeners), strongly prefer that the piece end in a logical and expected place. Perhaps that is the most musical choice. "And they all lived happily ever after."

But one thing I like to try is to subvert expectations - try to end the piece with the listener in wonder. Either amazement because they didn't see the ending coming, or, in reflection because I left the ending ambiguous, and it is almost up to the listener to decide how exactly it ended.

Of course, all of this speaks very little to converting emotions into music. That tends to be a highly subjective topic anyway. But, what I'll do with this information after I've done this exercise is to write down every single technique that I can come up with that will convey those emotions using the instruments I have on hand for that piece.

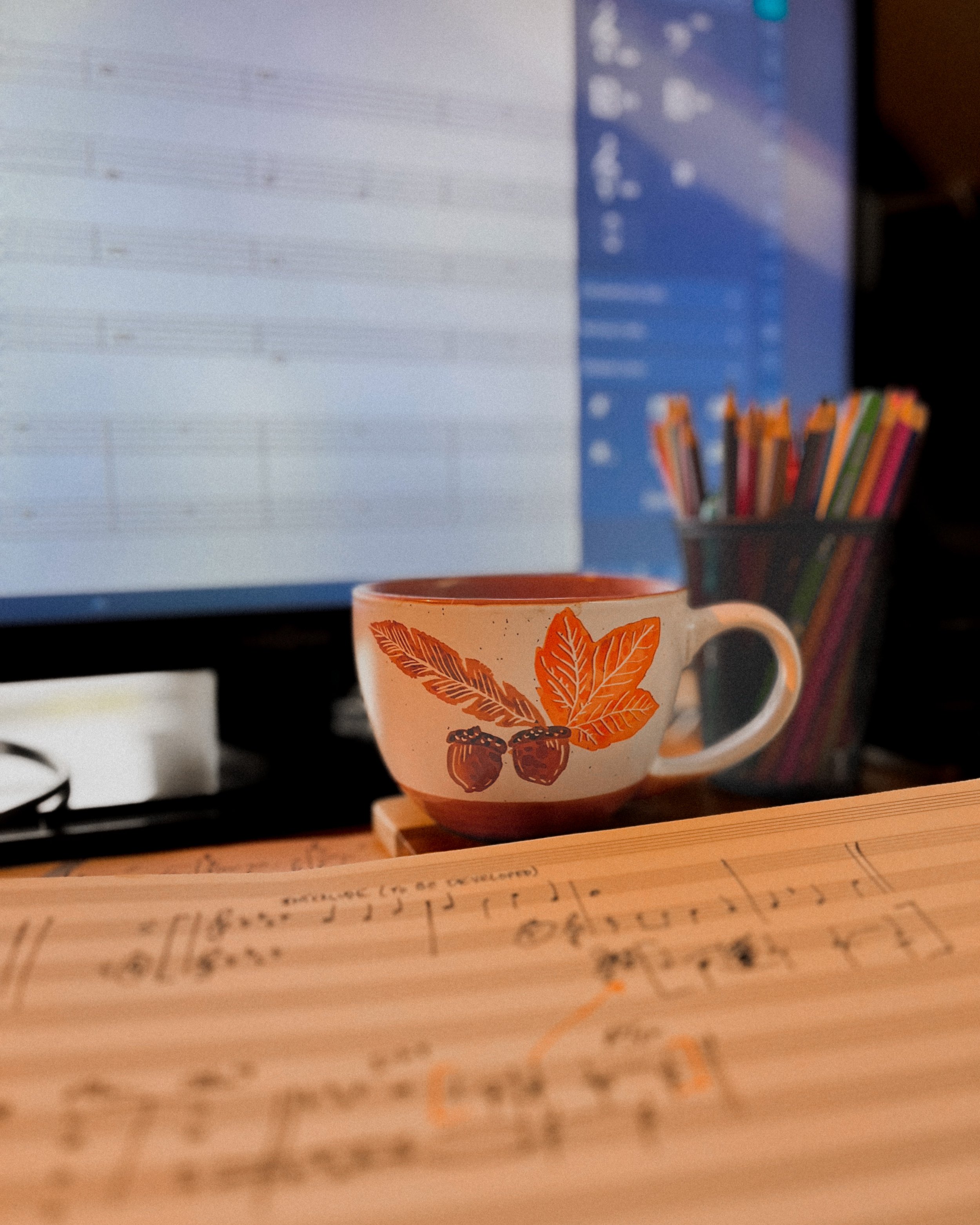

The picture I've attached is from a piece where I wanted to create uncertainty - almost like a fog or a mist; and to the right you can hear how that translated to music.

How do you create emotion in your music? Is it a process like I have just spelled out? Or does yours flow a little more fluidly? Let me know in the comments below.

And if you find this insightful, consider subscribing to my email newsletter:

If you’re looking to learn more about composition and would like to work with me, I’d love to tell you about the different options I’ve got for that. Click here to learn more!

Exploring Take Five's Brilliant Use of 5/4

Take Five is one of the best selling jazz singles of all time. I've always been fascinated by its use of the 5/4 meter. Today we are looking at how the Dave Brubeck Quartet took this simple idea in a complex meter, and made it into a masterpiece.

Take Five is one of the best selling jazz singles of all time. I've always been fascinated by its use of the 5/4 meter. Today we are looking at how the Dave Brubeck Quartet took this simple idea in a complex meter, and made it into a masterpiece.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

Four Things Every New Composer/Songwriter should do

1. Choose Consistency over Quality

Your first compositions aren’t going to be your best. And that’s frustrating - but consistency matters more at this stage. Practice writing a lot - and move on to the next piece. One nice thing about cooking is that it forces you to go through the process and then do it again. You can’t “keep working” on the same grilled cheese sandwich. Cook it, learn from it, try it again. Consistency in the long run will lead to quality.

2. Listen to Music Closely

Really take note of the techniques that other composers are using. Analyze the music, dictate the music, copy the scores by hand, learn to play it on your instrument. This is something else you’ll get better at the more you do it.

3. Listen Widely

I recommend this for any musician, regardless of specialty. Don’t just listen to music in your genre - study across as many genres as you can. You live in a world of infinite genres, let all of them influence your voice.

4. Be Endlessly Curious

Study other arts, ask a lot of questions, experiment constantly, take as many notes as you can, write down everything that comes to your head. I’d wager that every artistic innovation was spurred by curiosity. A lack of curiosity will lead to playing it safe. This is a composer’s best friend, but it is often overlooked. So be curious, and stay curious.

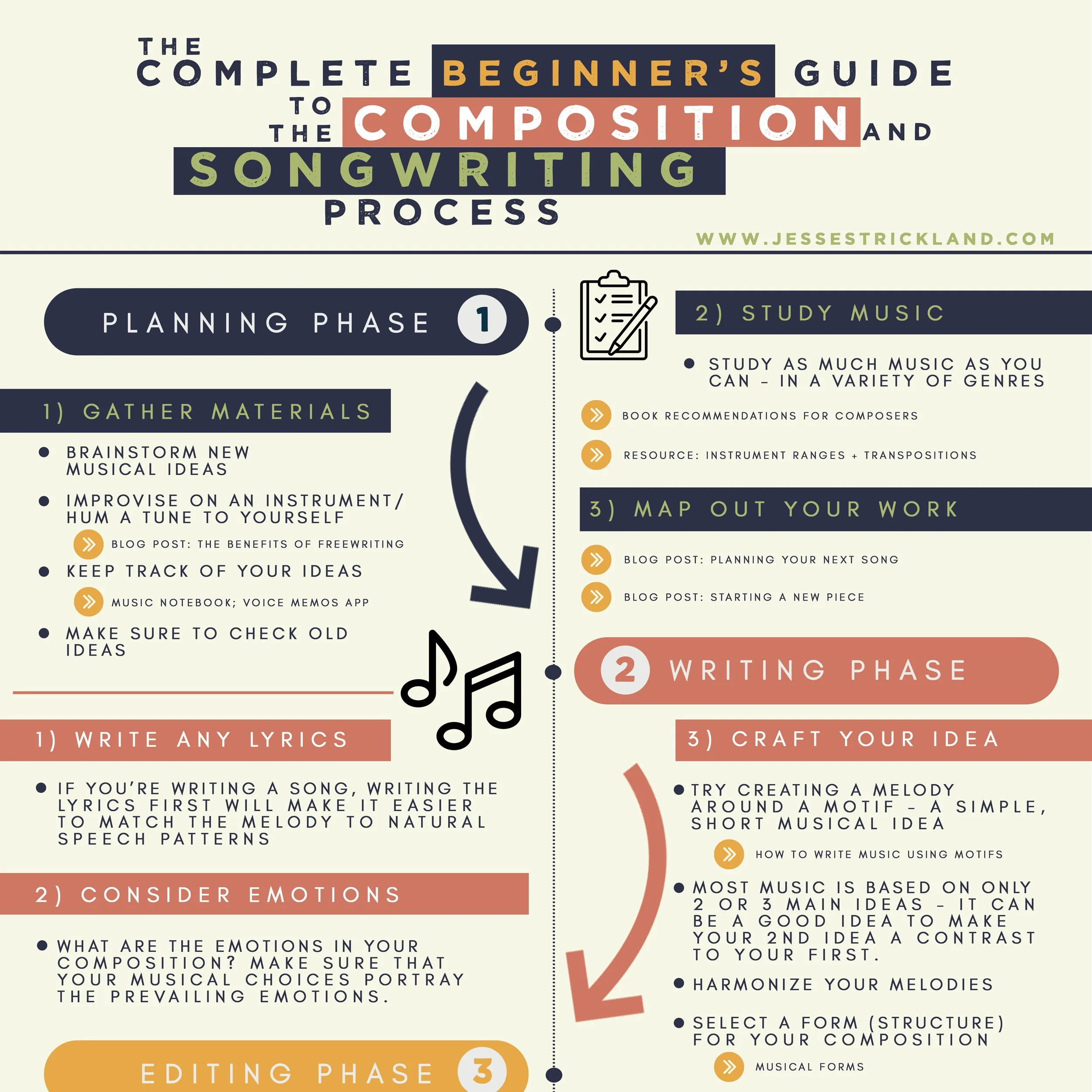

Check out this guide

If you’re new to writing music, I’ve got this free interactive PDF guide to the composition and songwriting process - check it out!

A List of Music Recommendations and Gear I Use

I get asked rather often what I use in the studio to create music, or if I have recommendations for books and such for younger composers. So, I decided it might be helpful to have all of those things together in a single list.

Books

Music Theory

Music Theory and Composition: A Practical Approach (Textbook)

Theory of Harmony (Schoenberg)

Music of Lord of the Rings (Douglas Adams)

Music History

The Oxford History of Western Music (Taruskin - 5 volumes)

A History of Western Music (Burkholder - single volume)

Composition

Behind Bars: The Definitive Guide to Music Notation (Gould)

The Study of Orchestration (Adler) (if you only get one book, I’d get this one)

Fundamentals of Music Composition (Schoenberg)

How to Write for Percussion (Solomon)

Introduction to Post-Tonal Theory (Strauss)

Scholarly Articles (Free Online)

SMT Online - a quarterly journal for Music Theory and Music Analysis, usually has about 7-10 articles per edition.

AMS Journal - This journal features articles in musicology.

Supplies

Softwares

Equipment

Vanguard Alta Pro 263AB Camera Tripod

Rode VideoMic GO II Mountable Microphone

Note: This post contains affiliate links

Setting Realistic Writing Goals

To be clear:, I’m incredible at setting goals; I’m terrible at setting realistic goals. Maybe you’re there too. We get all of these amazing ideas in our heads.

I’m starting a composition #100daysofpractice or a #100daysofwriting whatever you want to call it - I’d just like to be more consistent. Well, I need a plan of some sort for where I’d like to be at the end of the 100 days (sometime in June) - and that’s where the problem lies. So, I thought “what if a student had asked me that question?” And well, we will see how it goes but here are three things I’ve come up with for setting realistic composition/songwriting goals.

Figure Out Appropriate Pacing

Take a look at your recent writing output. How much have you written over a certain period of time? You can probably expect your output won't be significantly more than that. Perhaps you finished 1 piece/song last month. You're probably not going to suddenly write 10 this month. Set a goal of finishing one piece/song, and if you get to more than that - Great!

If one of your goals is to be able to write more/write faster - then start where you are and work your way up incrementally. You can do this by setting Input Goals: "I will write 30 minutes each day." And if you want to build up incrementally: "Each week, I will add 10 more minutes to my writing time." Of course, all of that depends on your schedule and how much time you can actually devote to writing.

2. Factor in things that are writing adjacent.

I'll often work all day editing a manuscript and then feel like I didn't write at all that day. Which isn't true. These things that are associated with writing are critical parts of the writing process. These are things like Freewriting and Experimentation - where you are just playing around but not actually making progress on a project. Or maybe it's studying the work of another composer for their use of techniques. Or, practicing new techniques on your instrument - or figuring out with players what is physically possible or comfortable. Or perhaps like I mentioned, editing and revisions. All of these things are crucial, but they take time, and we need to factor in those things for setting realistic goals.

3. Set goals that are consistent with your long-term goals.

I have had periods where I wrote what I felt like I was "supposed to" write. If there's no one commissioning you to write a piece, there's no reason to spend time writing a piece you don't want to write. Make sure the things you are doing on a daily basis actually line up with your desired trajectory as a composer and songwriter. What can you write today that will serve as a stepping stone to where you want to go? Don't chase after every opportunity just because it's available. Set goals based on what is going to fulfill you artistically, and what is going to help you in the long run.

So, that's where I am today. Day 1 of 100. I'll be documenting this journey so make sure to follow along from now until June, and we will see where I end up.

The Art Of Music Theory

Music theory is often confused as being mostly about identification, but really - it's more about interpretation. Music Theory is an art. And it's an artform that is both valuable and practical for all musicians throughout their lifetime.

Music theory is often confused as being mostly about identification, but really - it's more about interpretation. Music Theory is an art. And it's an artform that is both valuable and practical for all musicians throughout their lifetime.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

Anyone Can Write Music

Writing music is a craft. It's not a rare gift only given to a select few. And because it's a craft - all musicians can and should write music. And today I’ve got an exercise for you to help you get started.

Writing Music is like Writing Language

Let's think about language for a second. That's what I'm using right now to communicate with you. I could have chosen to communicate with you through a series of colored dots - but that wouldn't have been as effective.

In order to communicate with language, you need to be familiar with that language. I can put together sentences of words and you understand them because I know a lot of words and their meanings, I know sentence structure, and I know what it is that I want to communicate. I'm not inventing any new words to communicate this with you - but I am writing. Well, speaking in this case - but I did write it down in the script before I started speaking. Well, and actually before I wrote this script I spoke these thoughts into my voice memo app. And before that, I actually wrote these... [It cuts off, I start the camera over] You get the point - these are thoughts that I am communicating, and I am capable of that because I have learned English. And these particular thoughts do not require me to revolutionize linguistics.

In the same way, all musicians have within them the ability to communicate through writing music - because they know music.

Composition is Just Expression

Just because you have it inside you, that's not to say you'll immediately be good at it. That seems logical enough. My daughter when she was learning to talk would put together sentences like "me want doing swing", but she kept practicing and now she knows that "I would like to swing" better communicates what she wants.

All composition is just a musical expression. And you "getting better" at composition is you getting better at communicating that expression. And like with everything else in life, that happens through practice.

There's never been more resources

And you'll need to practice quite a bit. But it's worth it. And you might say "I have no desire to compose for a career." But I think literally every single musician can and should regularly express themselves by writing their own music. I write a lot of English all the time despite not being a career Novelist. My goal in writing in English isn't to have my books read by the whole world. I wrote a text message a few minutes ago, and it doesn't mean that I have intentions of become Geoffrey Chaucer.

You've got a lot of resources to help you - more than there have ever been. Countless videos and courses on the internet that you can learn to write music. I had none of that 20 years ago when I was learning to compose.

Not only that. But there are so many resources for you to experiment and learn on your own. With DAWs and Instruments and what not. Spitfire Audio has a free version of their BBC orchestra library that gives you access to practice with a full orchestra. It's Crazy.

I've got a free resource for you today. I've heard from a number of my composition students that keeping track of the whole process of writing a piece is often overwhelming. So, I've got this interactive PDF that outlines the composition process step-by-step. It's got links to 16 additional resources that I think you'll find useful.

A Writing Exercise

If you're still thinking "well, that makes sense - but I already know that I can't write music," I want you to try this exercise. It's going to feel awkward. Fight against that feeling. Composition is messy. And here’s the thing. Our goal today isn’t to write a whole song, or a whole piece. The goal is to just write something. Here’s what I want you to do:

Step 1. Take out your phone, and find your voice memo app.

Step 2. Hum something to yourself. Anything. Long or short, doesn't matter. Don't worry about whether or not it is good. Don't overthink it. Just hum something.

Step 3. Do it again. You might as well leave that voice memo going - you never know what's going to happen. Try to get up to five.

Step 4. Listen back to your voice memo. Let's go ahead and quickly come to terms with the fact that it isn't a Radio quality recording and move past that.

Step 5. What do you feel like each snippet is expressing? Happiness? Confusion? Hunger? If composition is expression, what do the melodies you've come up with express?

Step 6. Identify some fragments that you really like. You're looking specifically for something you could build off of. Again, don't be too critical. You're looking for something that you like, not something you think is good. Or, even what you think other people might think is good. Your identification of things you like is a proof of concept that you can write music.

Step 7. Repeat this entire process quite a lot. Hum to yourself all the time. Eventually, humming a melody will be much easier. You'll end up liking more of what you came up with. And you'll better be able to say what your melodies are expressing.

I'd love to hear from you: do you compose music? If so what kind of music do you write? How did you get into writing music? And if you don't write music - do you want to? What obstacles do you see that keep you from it?

Planning Out Your Next Song

[Note: This is post #2 in a five part series on the composition process. If you have not read the introduction post, you can do so here. If you would like a free PDF of the material we’re covering, you can get your copy here.]

Now that we have an overview of the process, let’s zoom in and take a look at each of the phases - starting with the Planning Phase. Planning is a crucial part of the composition process, and it can set you up to have a much smoother writing experience. Maybe planning is something you do every time, or it may not be something you’ve ever thought about. I’ve got four steps, and they should help you stay organized in the writing process.

The Importance of Planning

First things first, let's talk about why planning is so important. By taking the time to plan your composition, you can:

Create a roadmap for your music

Stay organized and focused throughout the writing process

Create a cohesive and intentional piece of music

Avoid writer's block and other creative roadblocks

Improve your productivity and efficiency

Avoid creating problematic music, that you might have to go back and fix all of those mistakes later.

Without a plan, it's easy to get lost in the creative process and lose sight of your goals. I sometimes get caught up in just writing, and almost inevitably I end up having to go back and come up with a plan so the piece isn’t a complete mess.

Other times, you might hit a wall and have no clue where to go with the piece next. But, with a plan, you can always go back and check the map. Having that plan will usually improve your efficiency in writing the piece.

Collect Musical Materials

Before you start planning your piece, collect musical materials that will serve as the building blocks for your composition. Maybe you’ve had an idea in your notebook, and now you’re getting around to writing it. Maybe you’ve got sketches all over the place (on napkins and whatnot) and they need to be consolidated. By collecting these musical materials, you'll have a pool of resources to draw from when you start planning your piece.

I used to try starting from absolute zero with a plan, and then I realized that was a terrible idea - at least for me. It’s definitely better to have some materials that you can use to create a plan with.

If it’s a song with lyrics, I will at least have some of those lyrics on hand for this planning phase. You don’t have to have all of the lyrics completed, just enough for you to know the central ideas of the song.

Purpose of the Piece

What kind of music are you creating, and what's the goal of the piece? Is it a pop song that you want to pitch to a record label, or a cinematic score that you want to use in a film? Defining the purpose of your piece can help you stay focused and ensure that your composition aligns with your goals. Of course, not all music has to have some greater “purpose”, it can just be music. Also, if you’re writing for a performer or ensemble, they might have some purpose for the piece (like an anniversary, or the dedication of a new auditorium…something like that)

You might also consider what sort of meaning the piece has. Is it a love song? Is it a piece about the grandeur of nature? Is it a piece that represents some scientific or mathematical principal? Again, music doesn’t have to have a “meaning”, but if it does, the planning phase is a good place to figure that out.

Scope/Instrumentation

Next up, it's time to consider the scope and instrumentation of your composition. What instruments do you want to use, and how will they work together to create a cohesive sound? How long will the piece be? Is it multi-movement? Is it a single song, or an idea for a full album?

Sometimes this is really easy. You’ve been asked to write for a particular ensemble, and that ensemble has given you some parameters. Like this piece I wrote for a percussion ensemble. It was for 4 performers, and I was told to keep it under 15 minutes long. Furthermore, because of the nature of this ensemble, I was asked to only use metallic percussion instruments. So, those decisions were made for me; which means in the planning phase, I wasn’t deciding which instruments to use, so much as how I would use them.

Other things to consider here (and it’s okay if you don’t know them just yet): What key will you be in, and what tempo will you set? Consider the genre and style of music you're working with, as well as the emotional journey you want to take your listeners on.

Emotional Journey

Speaking of emotional journeys, it's important to think about the emotional arc of your composition. What kind of mood or atmosphere do you want to create, and how will you achieve that through your musical elements? Consider how the melody, harmony, and rhythm can work together to evoke different emotions and feelings in your listeners. You might even want to create a musical map that outlines the emotional journey of your piece, from the opening notes to the final resolution.

Timeline on an 11x17 paper

I like to start all of my pieces with a timeline, that I put on a single 11x17 sheet of paper. You basically start on the left with the beginning of the work with the end of the piece on the right. I like to start by marking time (in minutes and seconds). Then I’ll place the materials that I know I have where I want them (major themes, melodies, etc). You can also mark down emotion words, and colors, and energy levels - all the stuff you just figured out in that emotional journey section.

The Resources I Use

So what do I like to have on hand to plan a piece of music? Honestly, all you really need is a piece of paper and a pen to do what I have suggested above. But. Here are some items that I have found very handy in this process.

1) Like I just mentioned, I like to work on 11x17” pieces of paper. It just gives me more room for ideas. 8x11” is totally fine too, if that’s what you’ve got on hand.

2) This is my sheet music book of choice. It’s got 18 staves, so it’s great for working with a lot of instruments at once. If you want something more notebook sized, this is a good choice.

3) This is a pen that has 5-points so you can draw a music staff on a blank paper. Very handy.

4) I like to have a ruler on hand for marking straight lines and edges.

5) You might also find it helpful to have an instrument nearby - but honestly, I like to do this stage of the process without an instrument so that I focus on the planning, and not on the writing.

Final Thoughts

Planning is an essential part of the music composition process. By taking the time to collect musical materials, define the purpose of your piece, consider the scope and instrumentation, and create an emotional journey, you can create a cohesive and intentional piece of music that aligns with your creative goals. Plus, by creating a timeline to guide your composition process, you can stay organized and productive from start to finish.

But. Here’s the other extreme - that I’m also guilty of: you can spend so much time planning the piece that you never actually get around to writing it. At a certain point, you’ve got a good enough plan, and you’ve just got to start writing. The piece will become something you never intended - but that’s okay, you’ve also got to be willing to listen to what the piece wants and where it wants to go…but that’s a completely different blog post.

So - if you’ve never done it before - the next time you sit down to write a new piece of music, take the time to plan it out. It may seem like an extra step, but in the long run, I have found that it will save you time, energy, and headaches.

Next time, we will talk about the actual writing phase of the composition process. I hope you’ll join me. Make sure you’ve got your copy of the Beginner’s Guide to the Composition + Songwriting Process.

further reading

Introduction to the Composition + Songwriting Process

Why have a Process?

There are a lot of steps and a lot of moving parts when writing a song, or a piece of music. This is why it's really easy to get stuck and frustrated, or even to abandon a project entirely.

It's much easier to accomplish anything if you've got a plan. And for years in my own writing journey, I would constantly get stuck. Whenever I would begin a new piece, things would start off great, until I hit some sort of a wall, and it was like trying to reinvent the wheel every single project. So, I finally had to sit down and write out my personal process for writing a piece of music. Anything that I did that made writing a piece easier, or anything that if I didn't do - I'd have to come back later and do it anyway. Take all of that and put it in a nice linear format, and you've got yourself a bit of an algorithm for writing music.

Of course, it doesn't quite work that nicely. Composition is a messy art. It's not linear, and that's exactly why you need a map. Something you can go back to when you end up lost off the beaten path and unsure which way to go now.

Each and every composer needs their own personal process - we each have a different brain. Our field is an art. This is not a McDonald's, where the goal is to put out an identical product each and every time. We each have our own voice, and our own personality, and our own workflow which produces the results that we want.

However, I think there are four phases to the composition process, regardless of the composer; regardless of the style of music, or era of history.

This is the start of a Five Part series, taking an in-depth look at the composition process. Today, I'll just give an overview of the four phases, and then the next four posts will look at each of them in more detail.

What makes it a composition?

Let's start by defining a composition. There are many ways to write music, and a composition is a specific type of written music. All of the types of written music are valid and good, I'm not trying to elevate one over another, I'm just trying to focus all of us on the same idea. Disclaimer: These are the definitions I'm giving for the sake of this series, other musicians might have varying definitions.

1. A Composition is Original

A composition is a work of music that is new and original to the composer who wrote it. This distinguishes a composition from an arrangement, or a cover. With arrangements and covers, (generally) another composer wrote the source material, and you are just putting your own spin on it. This takes a great deal of skill and consideration, but it's not what I'm talking about in this series. Maybe we'll do a different series on how to do a cover.

So, a composition then, is a work that all of the material is original to the composer (or composers, in the case of a co-write). That's important for our purposes because it gives a composition its own specific process.

2. A Composition is different from an Improvisation

The fact that a composition is planned separates it from an improvisation. You'll often find musicians who have a propensity towards one or the other. I am on the composition side. I have very little ability to improvise. I find that it is very similar to those who can stand up and give a rousing speech of the top of their heads, versus those who do much better to sit down and carefully craft a novel. It's often two separate skill sets.

There's also no editing an improvisation - you know, by definition. Once you've played your saxophone solo, it's over - there's no redo. Of course, once you get into the recording studio with jazz musicians, the line between composition and improvisation starts to blur.

But here we are talking about a planned, crafted, and edited work of music - known as a composition.

One other note: Some might make a distinction between a composer and a songwriter - but I do both and they both have the exact same process for me. So, these four phases apply to both songs and instrumental compositions.

A Free PDF

For this series, I've made an infographic PDF of the entire composition + songwriting process that we're talking about - and it's free when you sign up for my email list. It's also an interactive PDF, so it has links to 16 additional composition resources. You can get your free copy of it here, and follow along as we go the next four posts.

The Four Phases

So what are these four phases? You can break the composition process into the Planning Phase, the Writing Phase, the Editing Phase, and the Transferral Phase.

Planning Phase

Like I mentioned earlier, a composition is planned. Even if you start with a template (say "Verse, Chorus, Verse, Chorus, Bridge, Chorus"), that's still a plan. You're deciding a number of things about the piece before you actually get into the writing of it:

- What's it going to be about?

- What instruments are involved?

- What compositional techniques are you going to use?

- How long will it be?

- What emotions do you want to portray?

And maybe you don't know the answer to some of these things to begin with, but I have found deciding on some of these things before I start writing makes the process go a lot smoother.

The planning phase can look vastly different depending on the style of music. If you're writing film or video game music, the planning phase is very different than a piece that is not written for picture.

Writing Phase

Once you've got a pretty good plan, it's time to start writing. I have found this to be the least linear phase out of the four. I often like to think of the steps in this phase as a checklist rather than a progression. I'll work on a lyric here, a melody there, go back and work on that lyric, then oh, I just had an idea for the B section. It's a rather messy endeavor. This particular section is the place where I get lost most often - but that's why I developed a process. I can always go back and look at the process, and I can also go back and look at the plan I made during the planning phase.

The goal with this phase is to end up with a first draft. I tend to not try to do any fixing during this stage - just get it all out of my head as quickly and as orderly as possible.

Editing Phase

Three main things happen for me in this phase.

1. A music edit. I go back and listen to see what isn't working. A horn part that is not playable. A section where the pacing is too slow. A lyric that's clunky and a little cheesy. A transition that was too abrupt. Those sorts of things

2. Go look for feedback. Composition can be a lonely sport. You've been in your own head the whole time, it's time to bring some other brain into the process.

3. A Notation edit. Unlike the music edit, I'm just looking for things that are out of place in the score this pass. That dynamic marking is in the wrong spot, these two staves are too close to each other. Are my page margins wide enough? Super tedious stuff. Also, something that you may not need to worry about if your goal is to recording.

Transferral Phase

This one might need a different name, but it's the best single word I could find to describe this part of the process.

So we have our final composition - there are typically one of two goals:

1) Record it for audiences to listen to

2) Write it down to hand to players who will perform it for an audience to listen to

Obviously, this particular phase might depend on which style of music you're writing for - as more classical music tends to be the second option, and more popular music tends to be more of the first option.

Of course, there's always that third option where you're going to both write it down, and record it.

The point in all three of these options is that you are taking this idea that was in your head, and you are turning into something that can be understood by another human.

The Series continues...

So, that's a quick overview of the composition process.

Stay tuned for the next four posts where we will look into each of the four phases in detail. Starting with Planning Your Composition.

In the meantime, make sure to get your copy of the Beginner's Guide to the Composition Process.

[FREE] The Complete Beginner's Guide to the Composition Process

Free Interactive pdf guide

One thing I hear from composition students a lot is that the entire process of writing a piece from start to finish is a little overwhelming. I get it. There’s a lot of moving parts. The project has a lot of phases, and each phase has a lot of steps (and sub-steps). Especially for composers with ADHD (like me), it can feel nearly impossible to keep track of.

Maybe you’re a new composer, and you want to get started but how to even go about that is kinda paralyzing.

So, I’ve got a new resource here for you today. It’s an interactive infographic outlining the entire composition process. Each place you find a yellow arrow, there is a link to an additional composition resource that will help guide you on the process.

This resource is free, but it is an exclusive for my email newsletter subscribers. So, if you’d like a copy of it you can subscribe to my newsletter by filling out the form below. I’ll send out new composition resources and tips every week - I think you’ll find it super helpful.

How To Start (Over)

I’m trying to start writing music again - after about 6 months off.

I didn’t mean for it to happen…but sometimes life happens. And I think we have to be okay with that.

It’s an interesting to be working through. It’s not like I’m doing something I don’t like, or even learning something new.

This is a journal entry, of sorts, into my journey of starting over. I’ve got three thoughts that I hope will help you if you are in the same place.

1. Start Small

If you’ve been on an extended hiatus from composing, you might want to just try jumping back into your old routine. Let me tell you from my recent experience - it doesn’t work. It’s like I was a marathon runner and then I did nothing but sit on the couch and eat potato chips for five years…and my first day back I tried to run 20 miles…at my old pace.

Taking a break is fine, a slow start after a break is fine.

So, I’ve been trying to write for 5 minutes a day. Only 5 minutes. Whatever I get done in that time is what I get done. I’m going to stay at 5 minutes until I feel like I can write longer.

As you can imagine, not much can get done in 5 minutes. And that’s okay. But, it didn’t take many days until I had forgotten about time and I was going for 10 - 15 minutes.

So - give yourself the grace to start small.

2. Establish a Writing Routine

Once you’ve gotten back in the habit of showing up every day and writing - establish a writing routine.

Now. A quick caution here. If you had a writing routine before your hiatus, it might not work this time around. Your life situation may have changed, the amount of time you can devote may be smaller. And also, this is just the second step after ‘write for 5 minutes.’ So, establish a writing routine that will facilitate your composing where you are right now.

Establish when and where you will write. How long are these sessions? What do you want to accomplish? Remember to be realistic. Your answer here shouldn’t be: “three hours, and I’m going to write a 30 minute concerto today.” But maybe like, “a 30 minute session where I’ll write the A theme for a solo piano piece”

3. Find a Community

Composition can be a lonely sport. You just sit at your desk, just you and your thoughts. It can be very isolating. You also might have the pervasive thoughts:

“I’m the only one going through this.”

“Maybe I just don’t have it anymore”

“Everything I write is garbage”

I promise, there are other composers are feeling this. (I’d also like to say parenthetically, your identity as a composer isn’t based on productivity) A really good strategy for combatting this is to find a community of musicians and composers who are trying to learn and get better together.

That’s what I’m seeking to create with my new YouTube channel. You can check out more about that here.

There are also a good number of online communities that you could plug into. The /r/composer subreddit is a pretty good one - you can ask all of your questions, ask for feedback on your work, and see that there are others who are in your boat with you.

So, if you’re trying to start over, don’t get discouraged. Try these three things. And remember, it takes time.

Remember why you fell in love with composition in the first place. And just write.

![[NEW CHOIR MUSIC] Nothing Gold Can Stay](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/588ed41937c5818a6a0b577b/1719952741346-SS27G439T6YOX2RROGNV/IMG_3778.jpg)

![[FREE] The Complete Beginner's Guide to the Composition Process](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/588ed41937c5818a6a0b577b/1695052299448-FQ70RDLLDZLJF9XJM5CH/Comp+Infographic+SQ.jpg)